url

stringlengths 67

81

| content

stringlengths 8.48k

104k

|

|---|---|

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher

|

Published Time: 2021-10-10T10:22:21+00:00

A 19th century African philosopher: the biography and philosophical writings of Abd Al-Qadir Ibn Al-Mustafa (Dan Tafa)

===============

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

[African History Extra](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

=============================================================

Subscribe Sign in

Discover more from African History Extra

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Over 15,000 subscribers

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

Already have an account? [Sign in](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher)

A 19th century African philosopher: the biography and philosophical writings of Abd Al-Qadir Ibn Al-Mustafa (Dan Tafa)

======================================================================================================================

### including the three philosophical works attributed to him

[](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

Oct 10, 2021

5

Share

**On Philosophy in Africa**

Philosophy is simply defined as "the love of wisdom" and like all regions, Africa has been (and still is) home to various intellectual traditions and discourses of philosophy. Following Africa's “triple heritage”; some of these philosophical traditions were autochthonous, others were a hybrid of Islamic/Christian and African philosophies and the rest are Europhone philosophies[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-1-42388787)

While the majority of African philosophical traditions from the first category (such as Ifa) were not transcribed into writing before the modern era, the second category of African philosophical traditions (such as Ethiopian philosophy and Sokoto philosophy) were preserved in both written and oral form, and among the written African Philosophies, the most notable works are of the 17th century Ethiopian philosopher Zera Yacob, eg the '_Hatata_'[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-2-42388787)and the works of Sokoto philosopher Abd Al-Qādir Ibn Al-Mustafa (Dan Tafa) the latter of whom is the subject of this article

* * *

**Support AfricanHistoryExtra by becoming a member of our Patreon community, subscribe here to read more about African history, download free books, and keep this newsletter free for all:**

[PATREON](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64)

* * *

**Biography of Dan Tafa: west Africa during the Age of revolution**

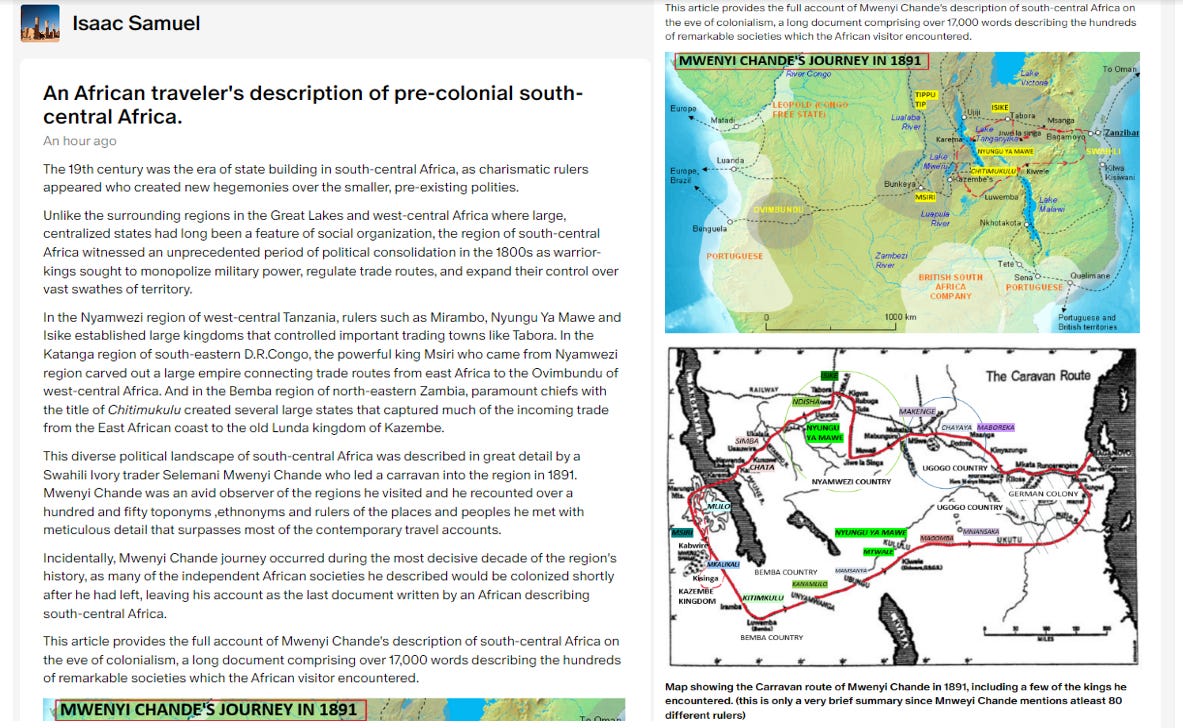

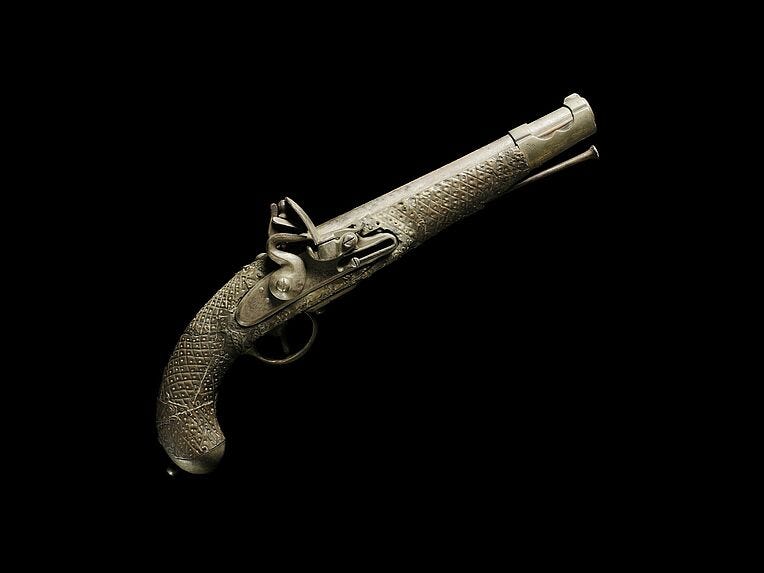

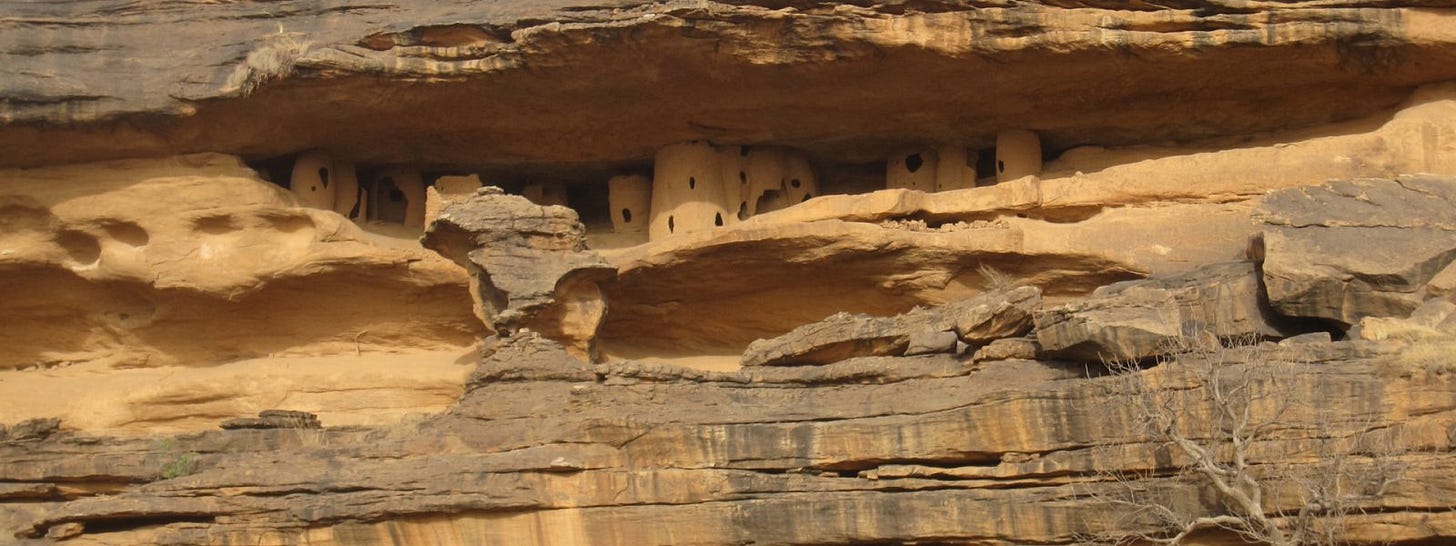

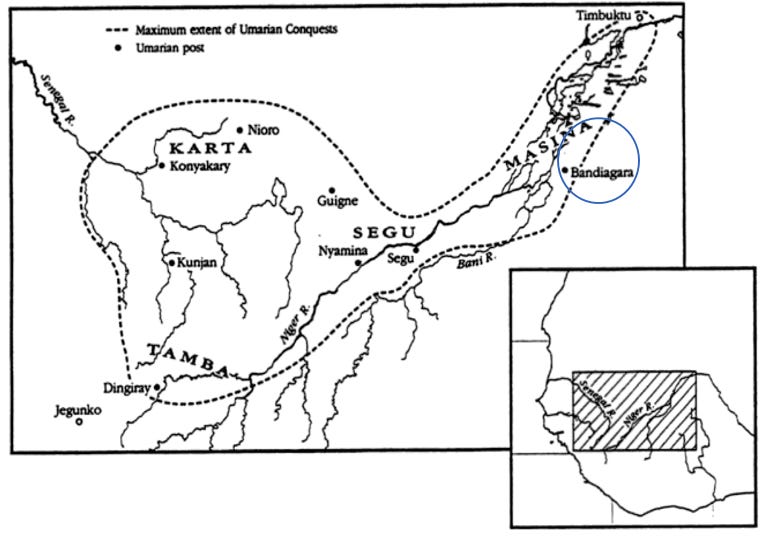

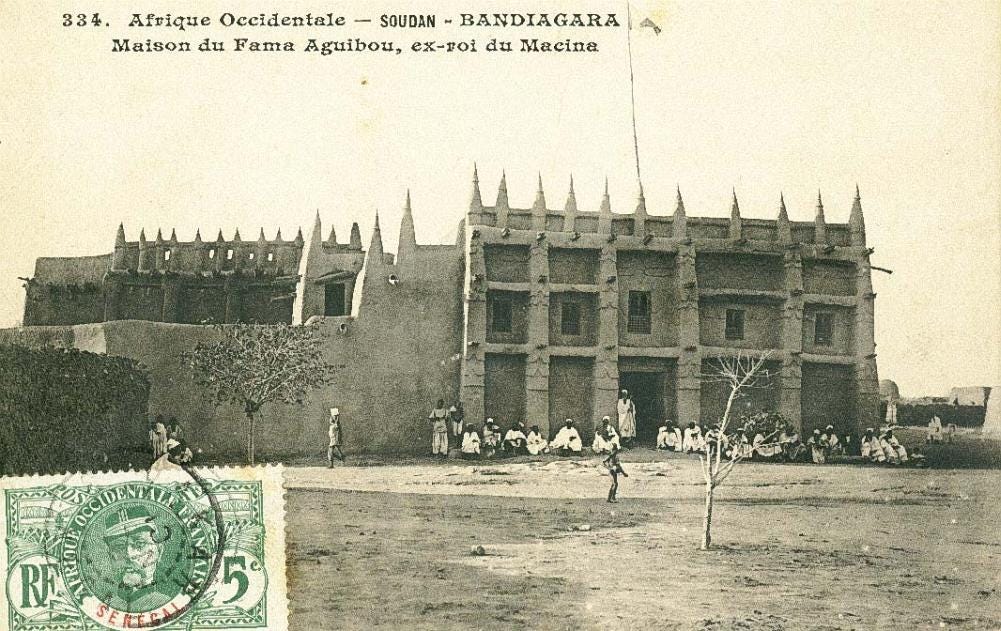

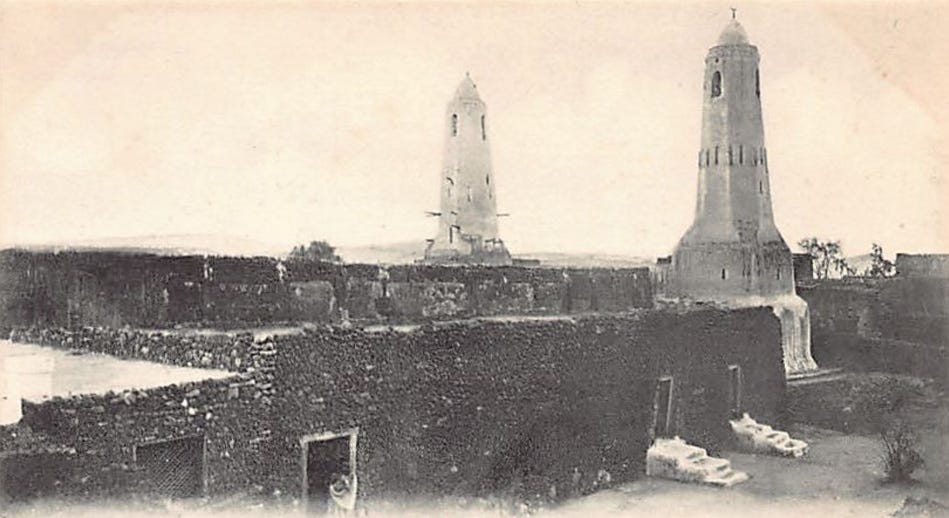

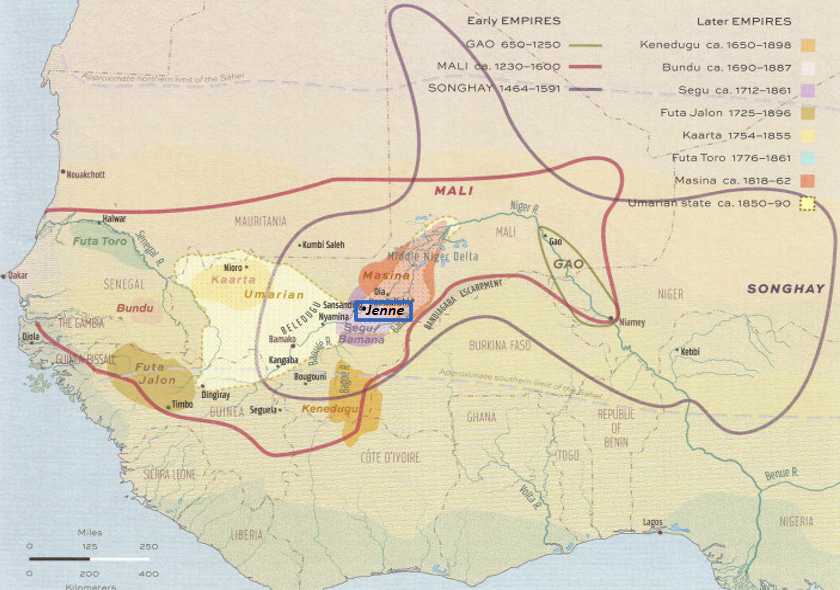

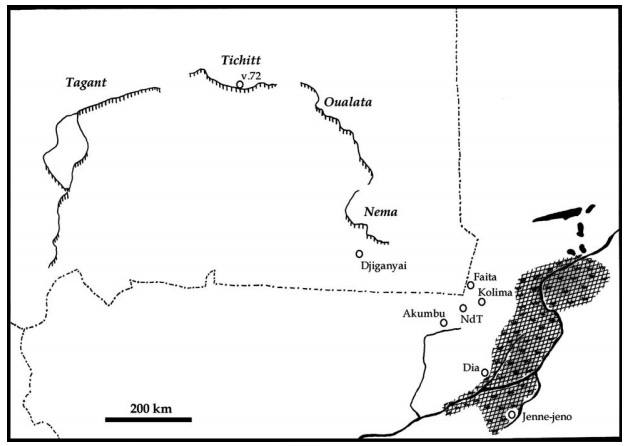

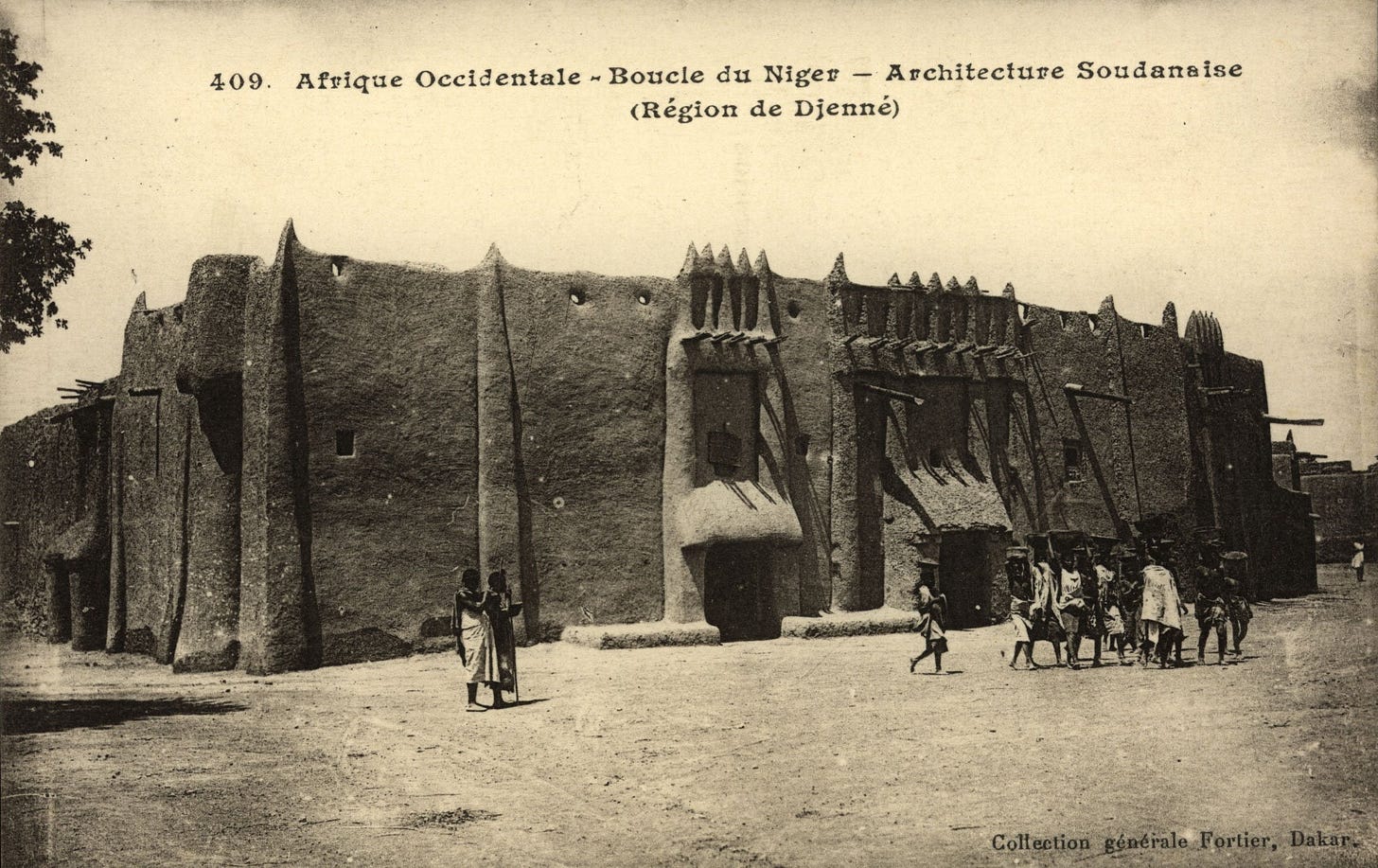

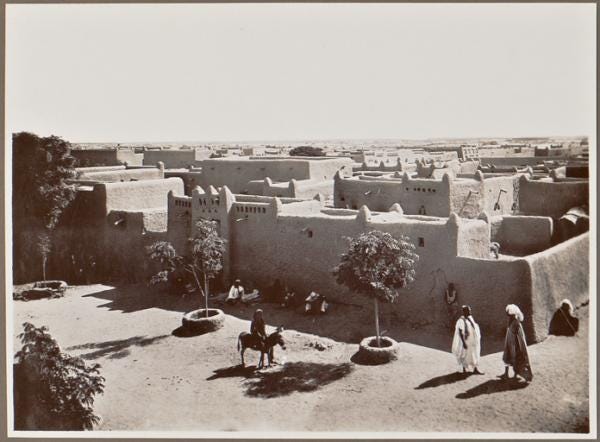

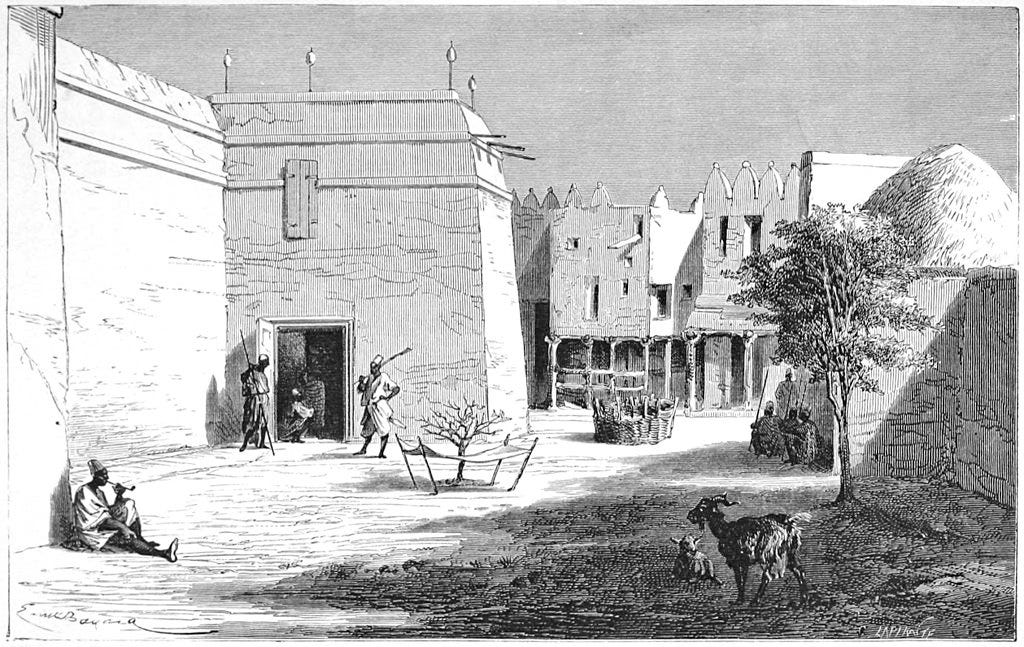

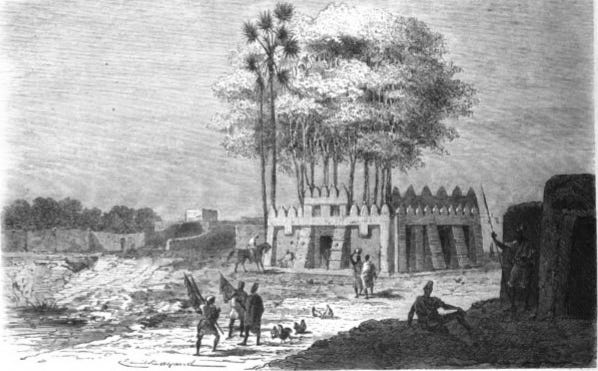

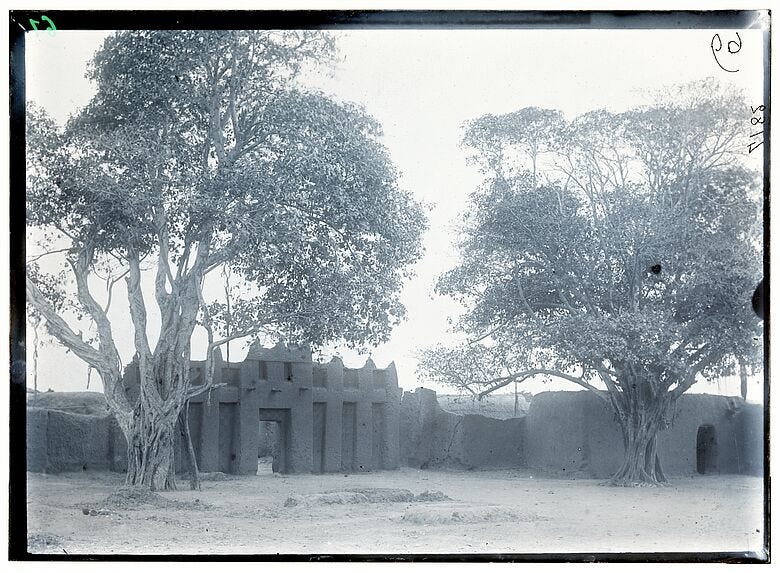

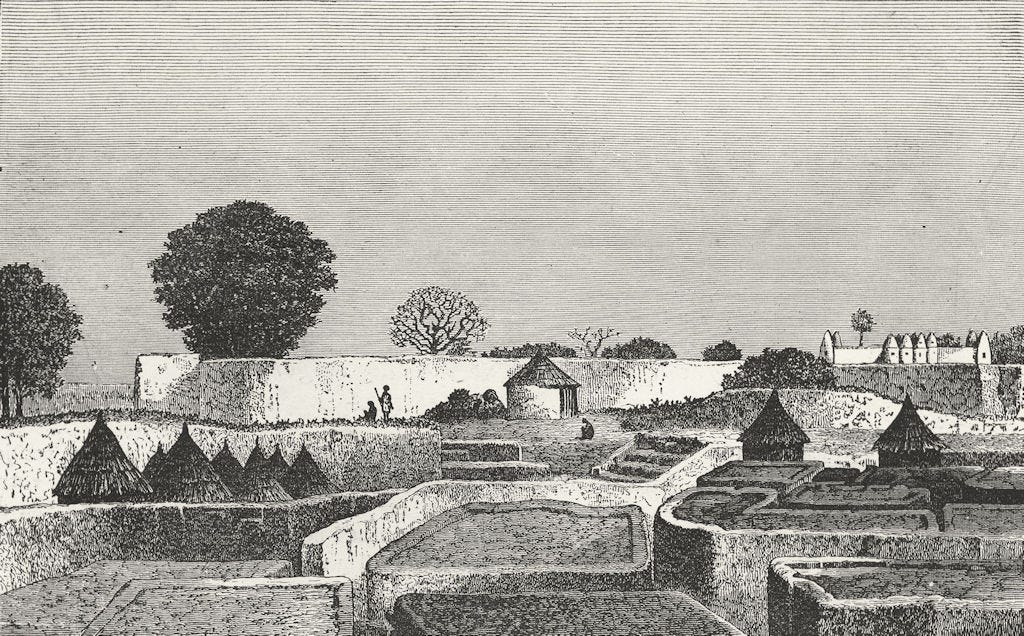

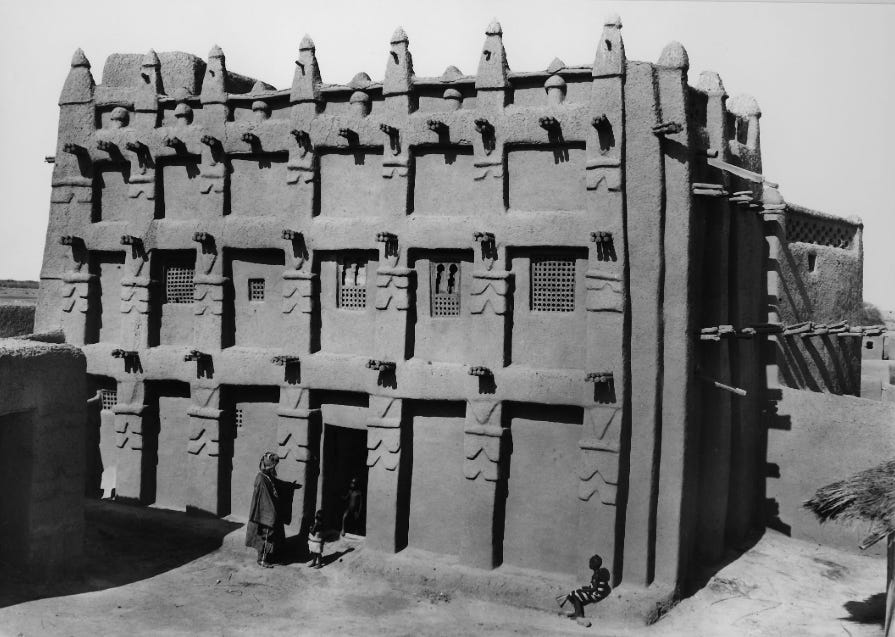

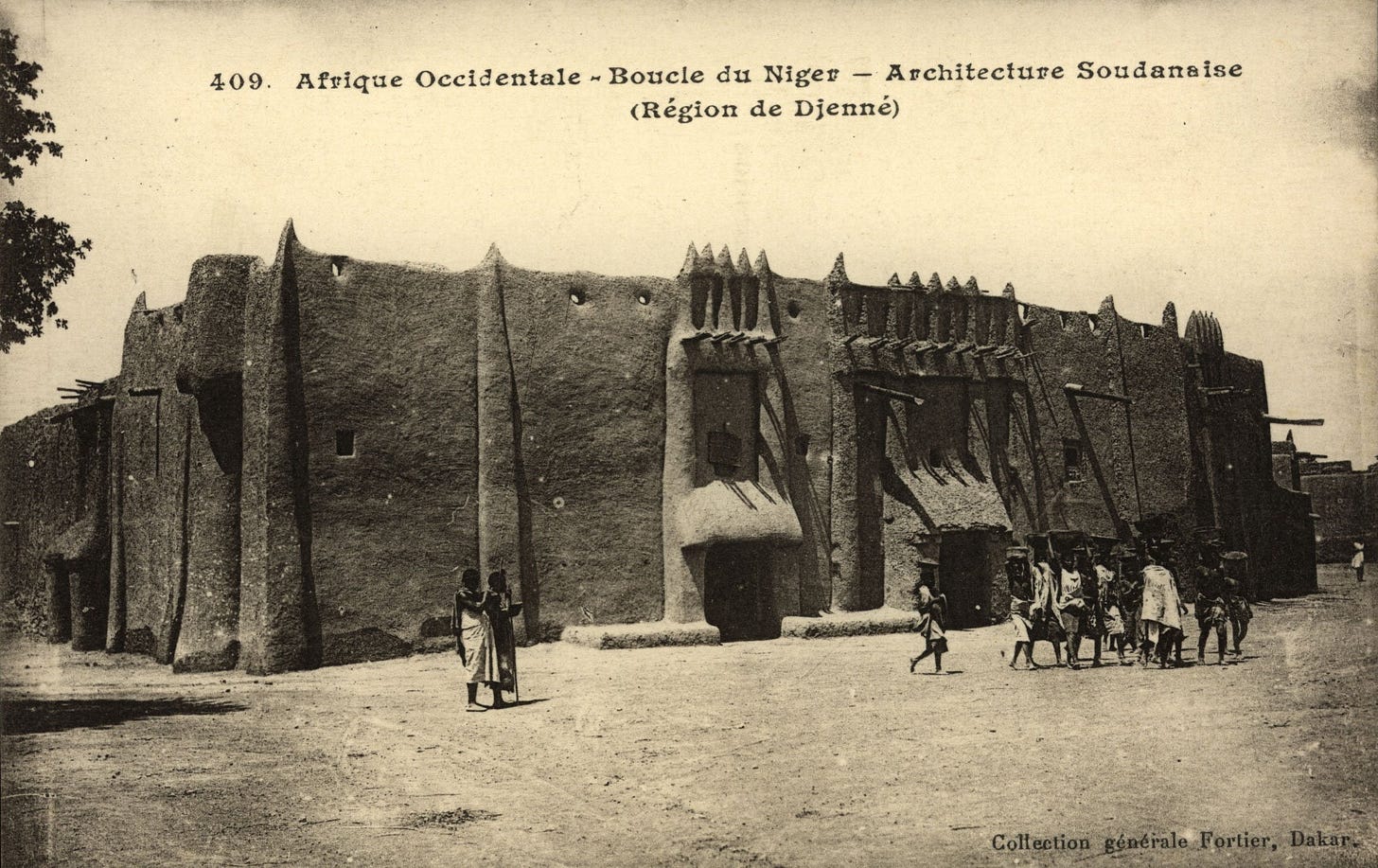

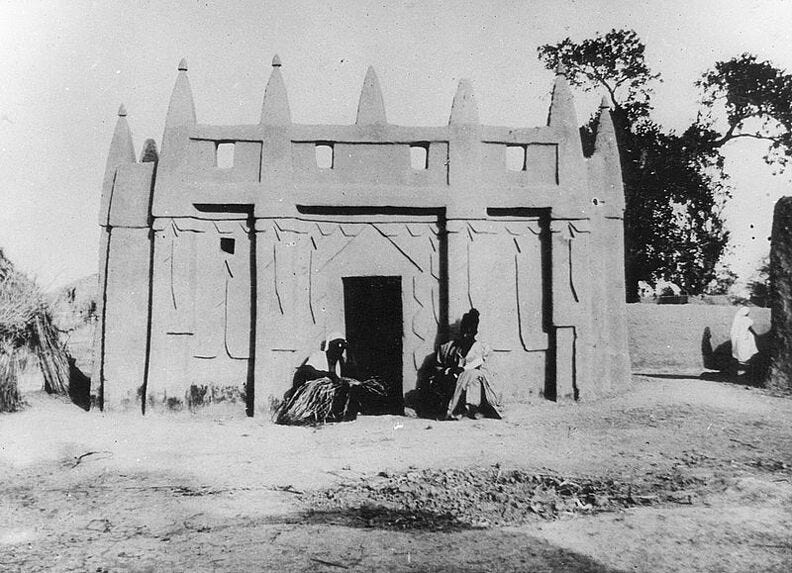

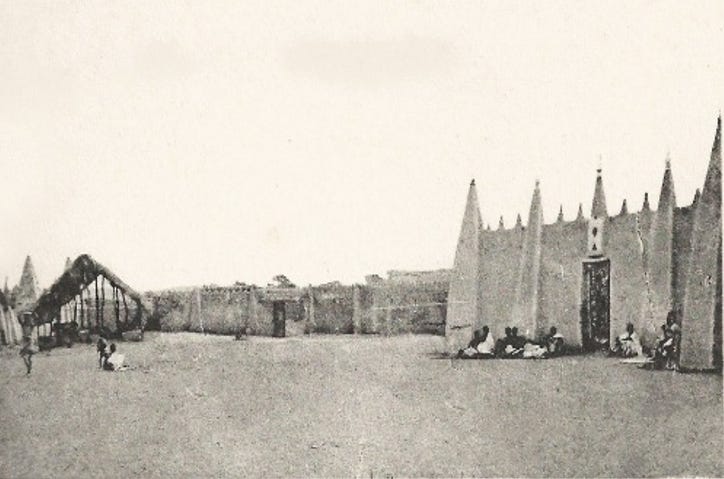

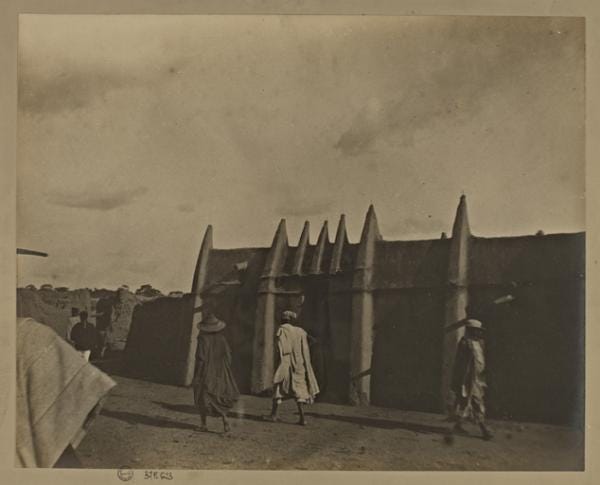

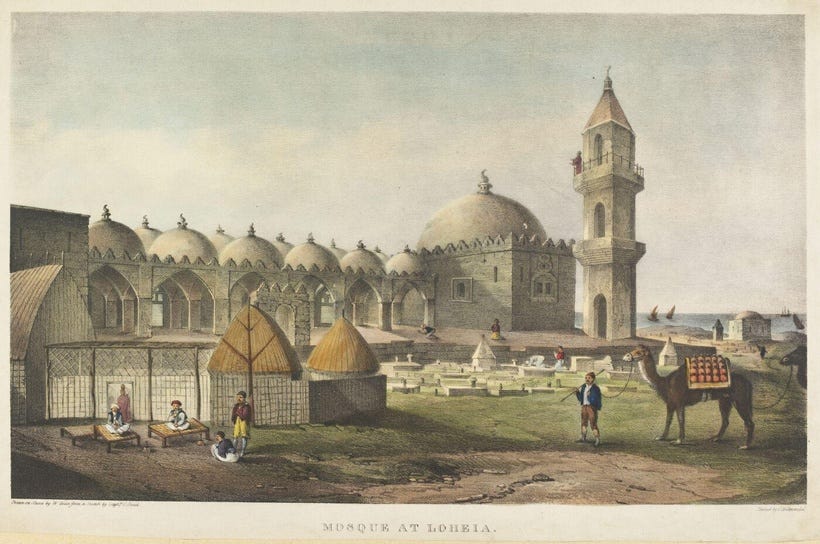

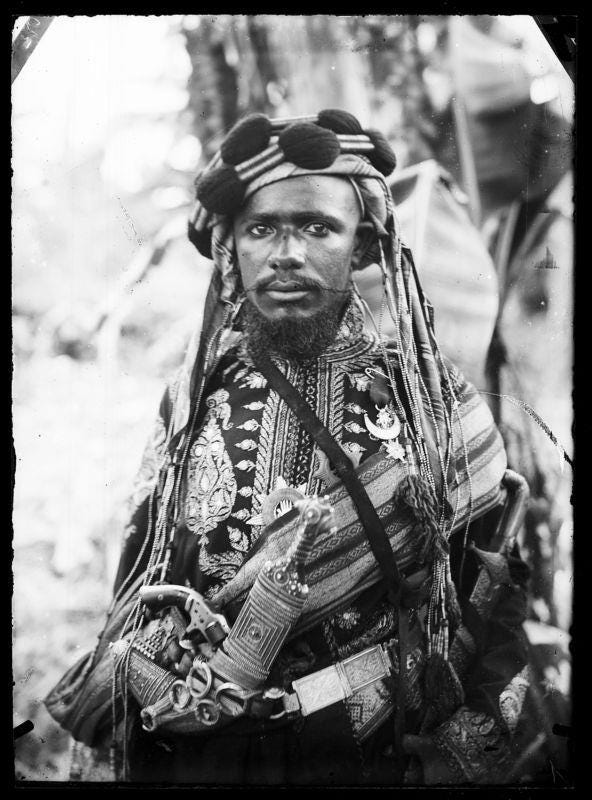

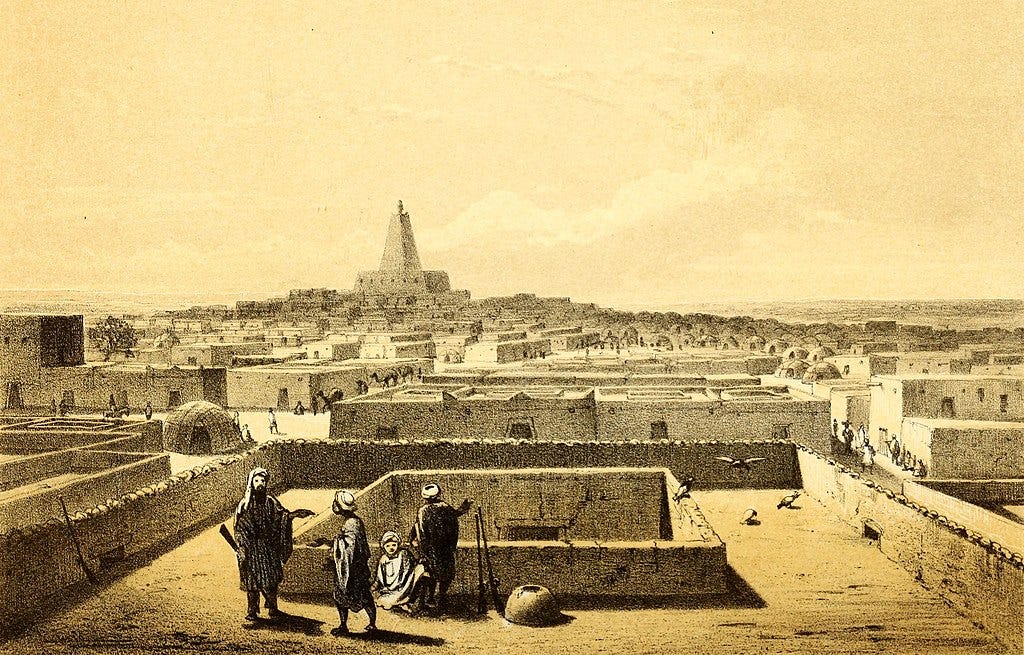

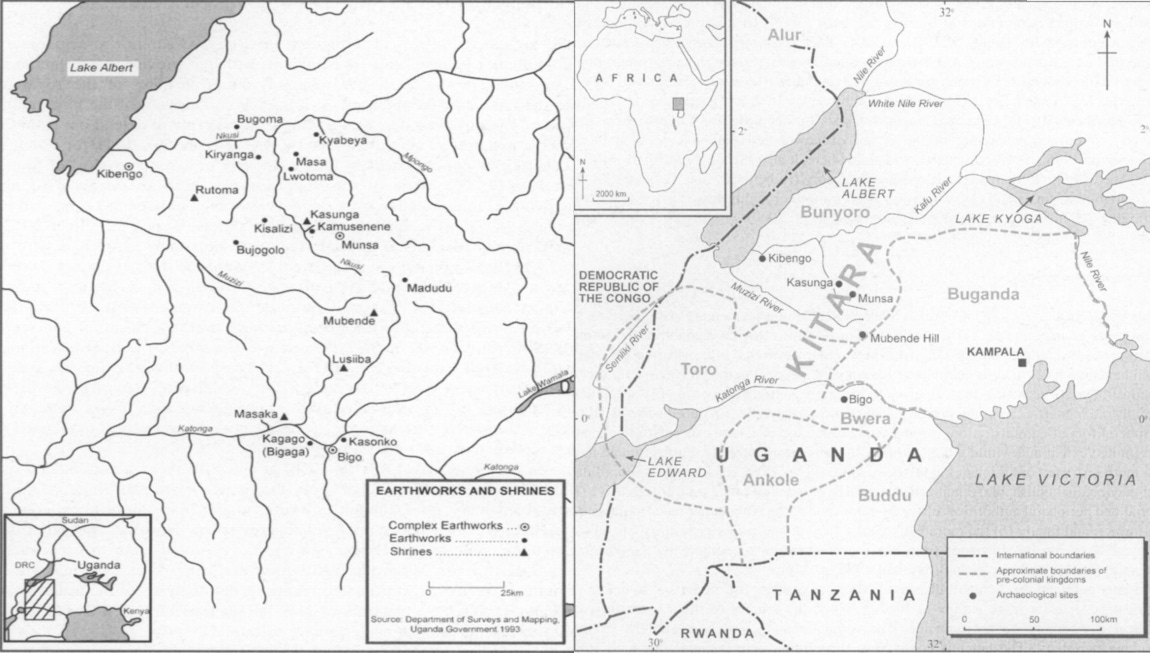

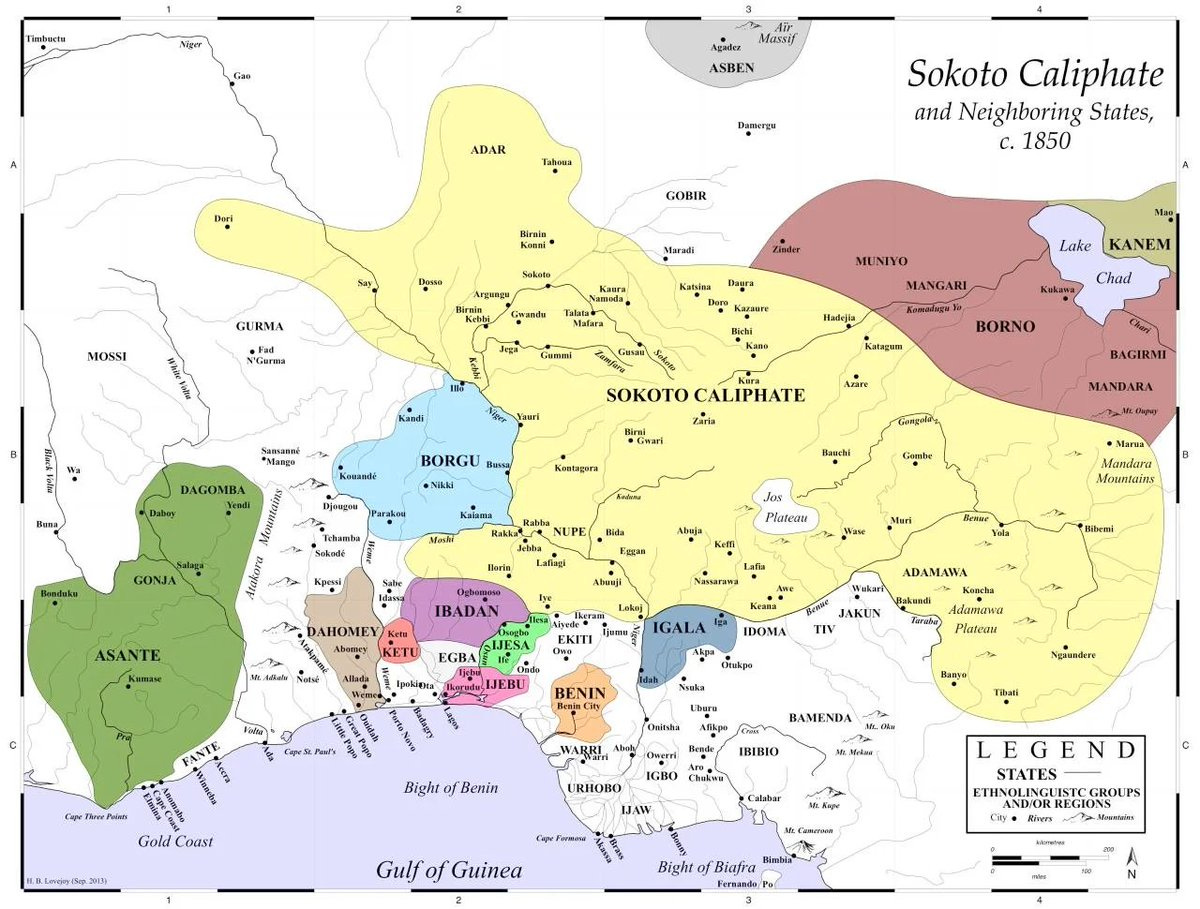

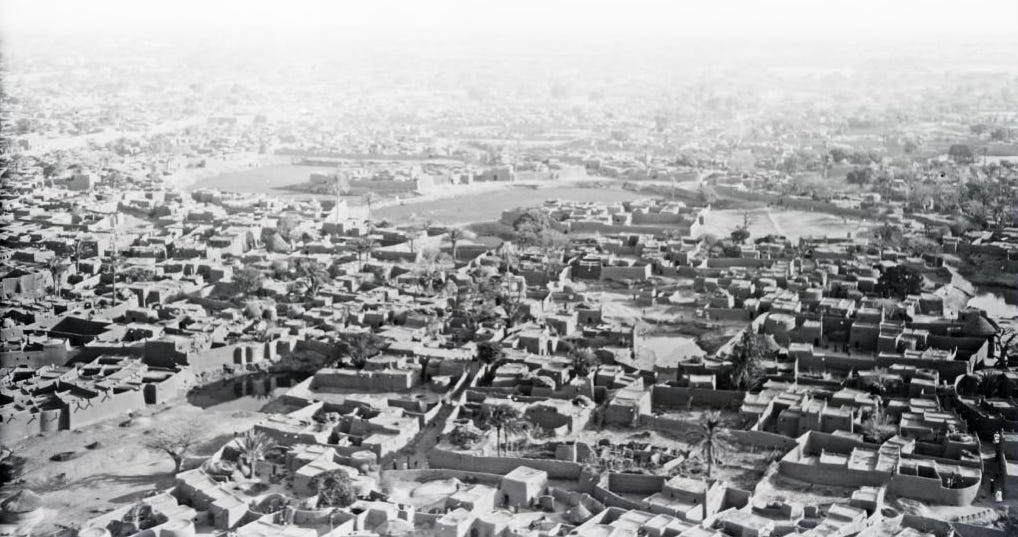

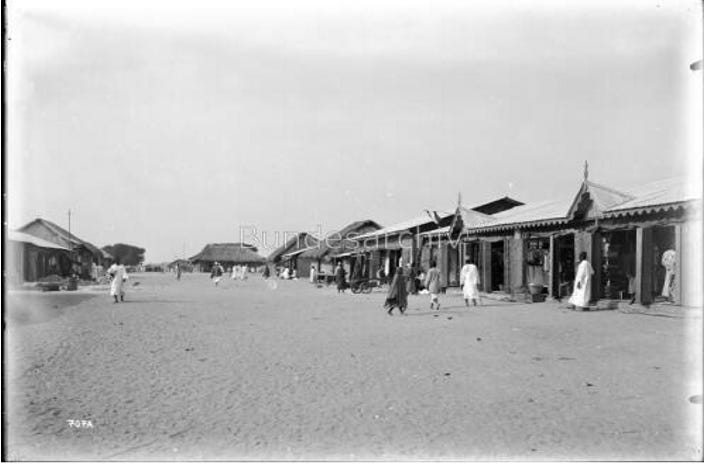

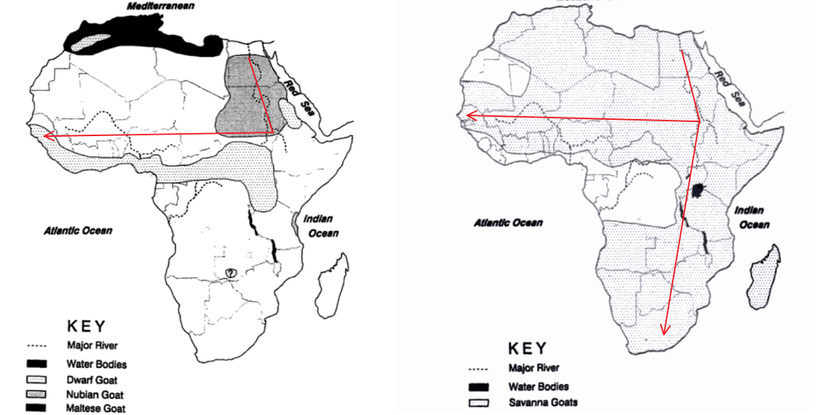

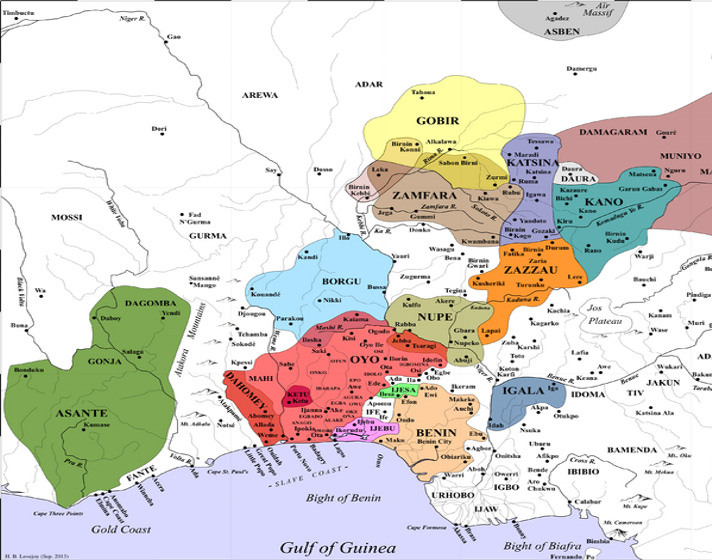

West Africa at the time of Dan Tafa birth was in the midst of a political revolution led by highly learned groups of scholars that overthrew the older established military and religious elites, leading to the foundation of the empires of Sokoto in 1806 led by Uthman dan Fodio and the empire of Hamdallayi in 1818 led by Amhad Lobbo, among other similar states.

_**Birth and Education**_

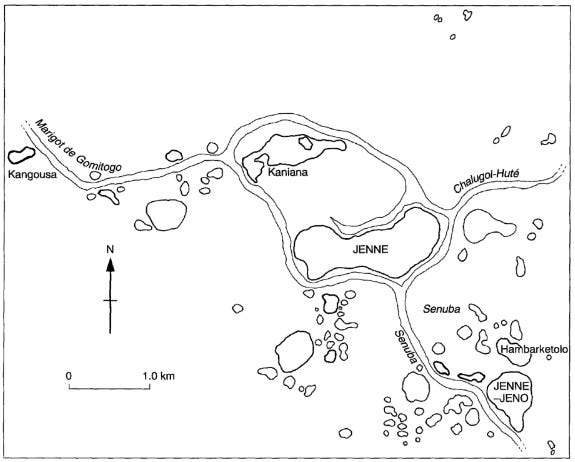

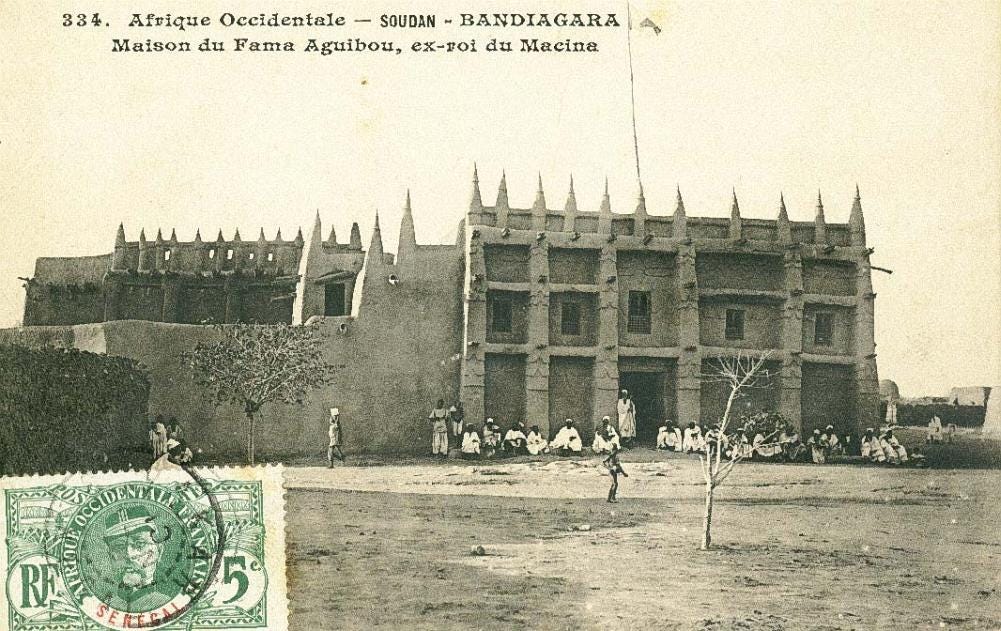

Dan Tafa was born in 1804, during the migration of Uthman Dan Fodio's followers which preceded the establishment of the Sokoto empire, he was born to Mallam Tafa and Khadija, both of whom were scholars in their own right. Mallam Tafa was the advisor, librarian and the 'leader of the scribes' (_kuutab_) in Uthman's _Fodiyawa_ clan (an extended family of scholars that was central in the formation of the Sokoto empire) and he later became the secretary (_kaatib_) of the Sokoto empire after having achieved high education in Islamic sciences, he also established a school in Salame ( a town north of Sokoto; the eponymously named capital city of the empire, which is now in northern Nigeria) where he settled, the school was later run by his son Dan Tafa.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-3-42388787) Khadija was also a highly educated scholar, she wrote more than six works[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-4-42388787) in her Fulfulde language on a wide of subjects including eschatology and was the chief teacher of women in the _Fodiyawa_ her most notable student being Nana Asmau; the celebrated 19th century poetess and historian[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-5-42388787)

**Dan Tafa’s Studies**

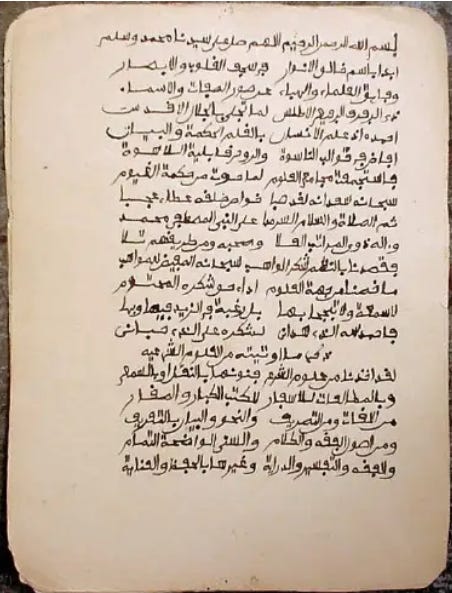

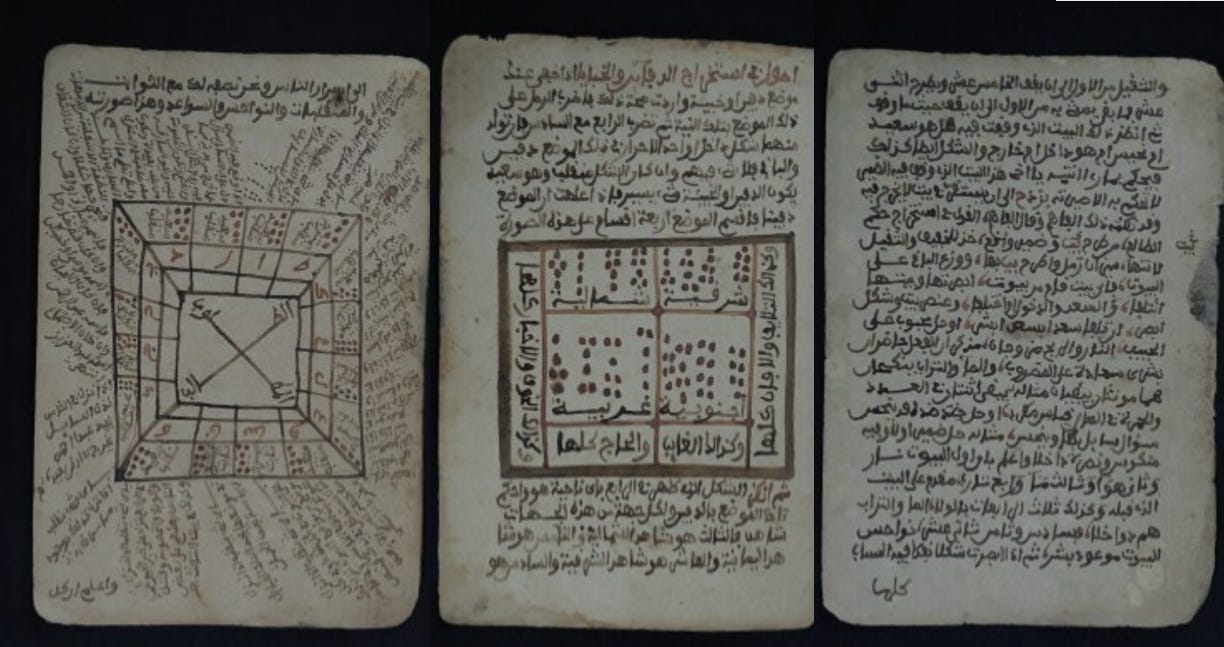

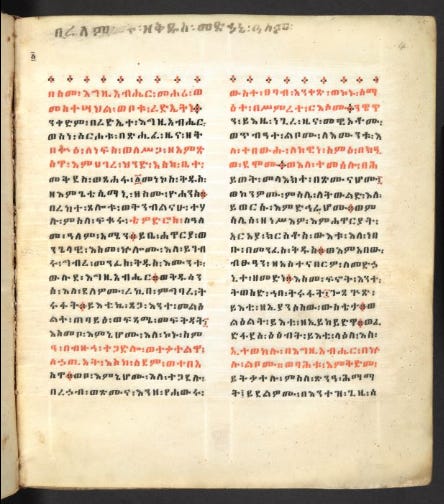

Dan Tafa studied and wrote about a wide range of disciplines as he wrote in his _‘Shukr al-Wahib fi-ma Khassana min al-'ulum’_ (Showing Gratitude to the Benefactor for the Divine Overflowing Given to Those He Favors) in which he divides his studies into 6 sections, listing the sciences which he mastered such as the natural sciences that included; medicine (_tibb_), physiognomy (_hai'at_), arithmetic (_hisaab_), and astronomy (_hikmat 'l-nujuum_), the sciences of linguistics (_lughat_), verbal conjugation (_tasrif_), grammar (_nahwa_), rhetoric (_bayaan_), and various esoteric and gnostic sciences the list of which continues,[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-6-42388787) plus the science of Sufism (_tasawwuf_). It was in the latter discipline that he was introduced to Falsafa (philosophy) under his main tutor Muhammad Sanbu (his maternal uncle), about who he writes:

_**"As for Shaykh Muḥammad Sanbu, I took from him the path of Taṣawwuf, and transmitted from him some of the books of the Folk (the Sufis) as well as their wisdom, after he had taken this from his father, Shaykh ‘Uthmān; like the Ḥikam (of Ibn ‘Aṭā’ Allāh al-Iskandarī), and the Insān al-Kāmil (of ‘Abd al-Karīm al-Jīlī), and others as well as the states of the spiritual path."**_[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-7-42388787)

In summary, "Dan Tafa was raised in the extraordinary milieu of the founding and early years of the Sokoto Caliphate exposed to virtually all of the Islamic sciences transmitted in West Africa at the time, from medicine, mathematics, astronomy, geography, and history, jurisprudence, to logic, philosophy, Sufism".

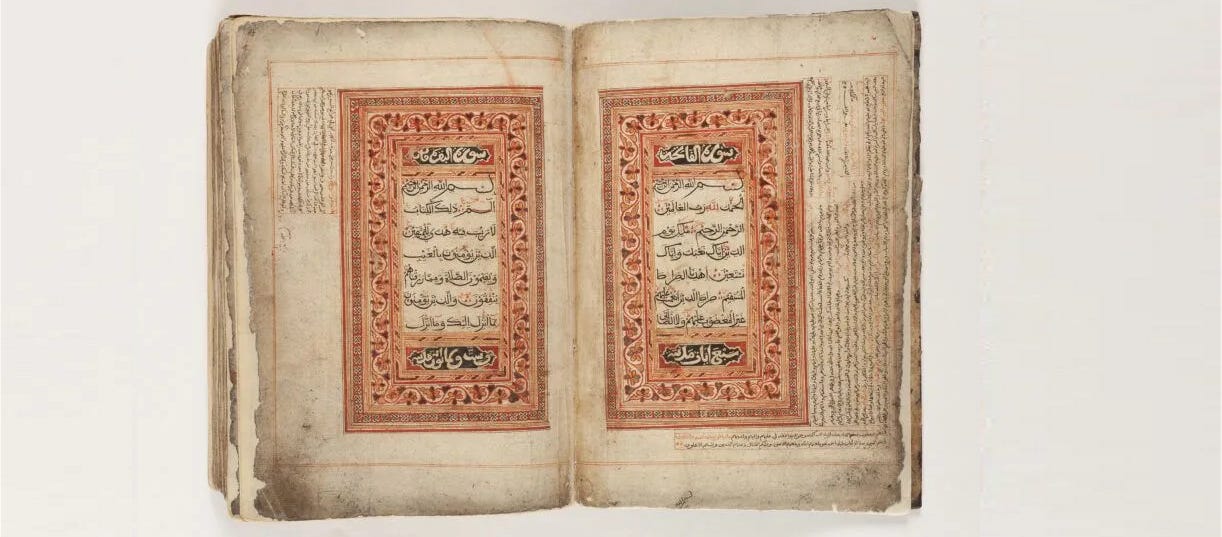

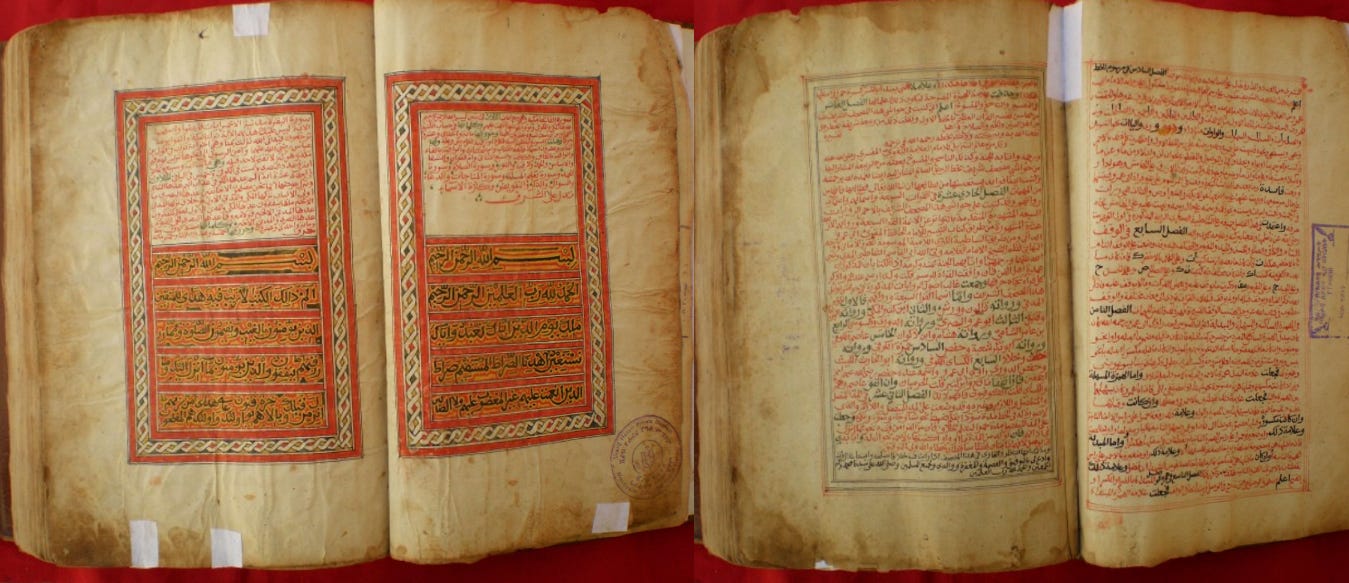

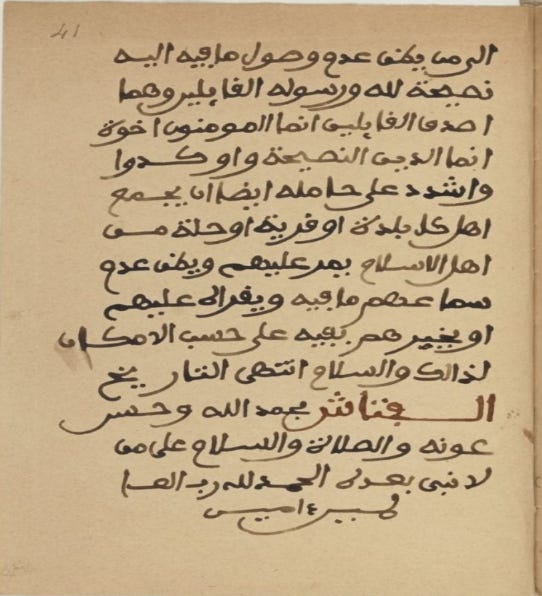

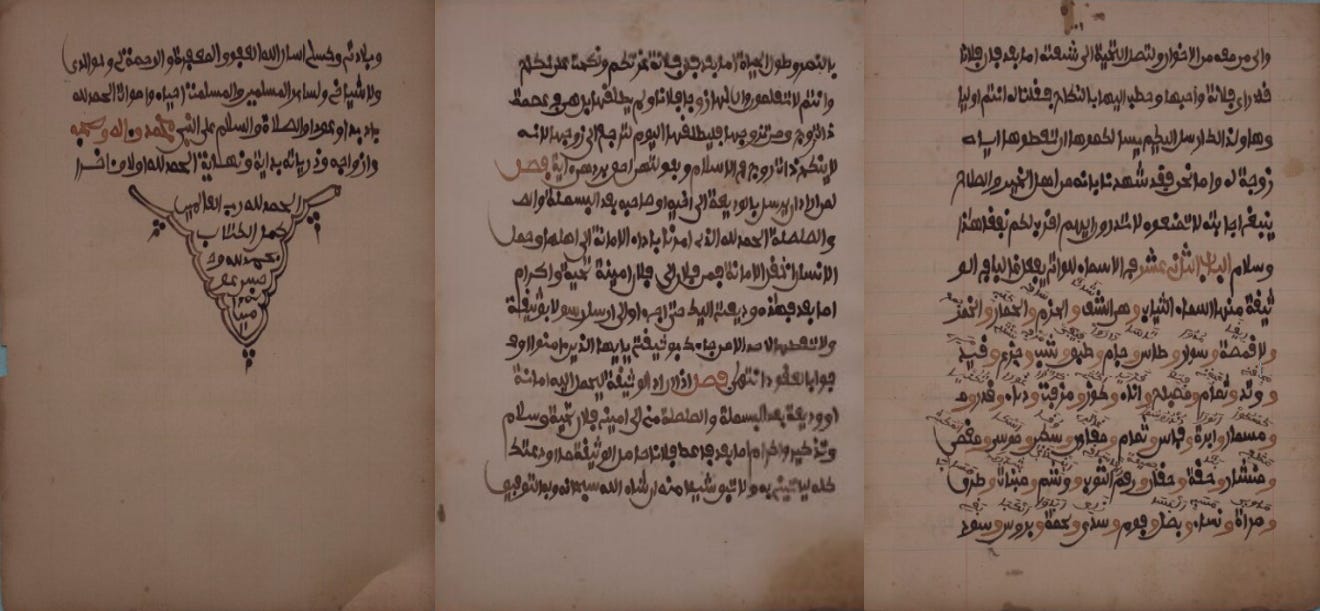

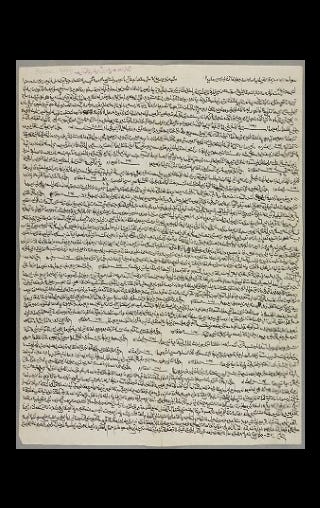

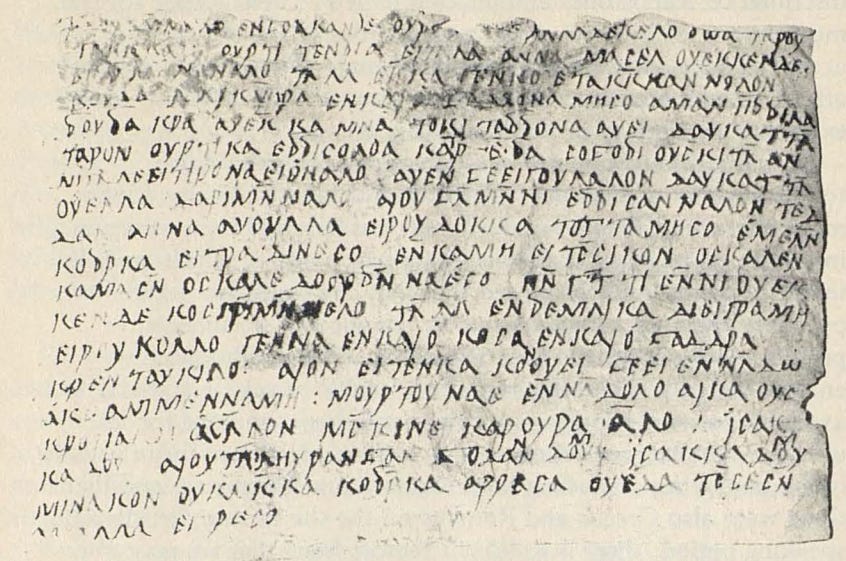

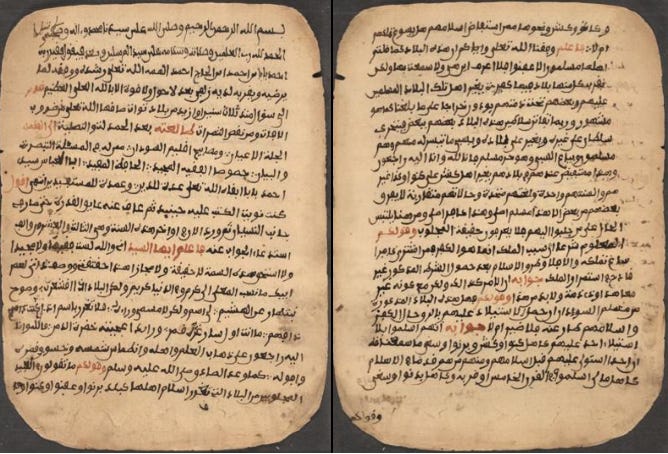

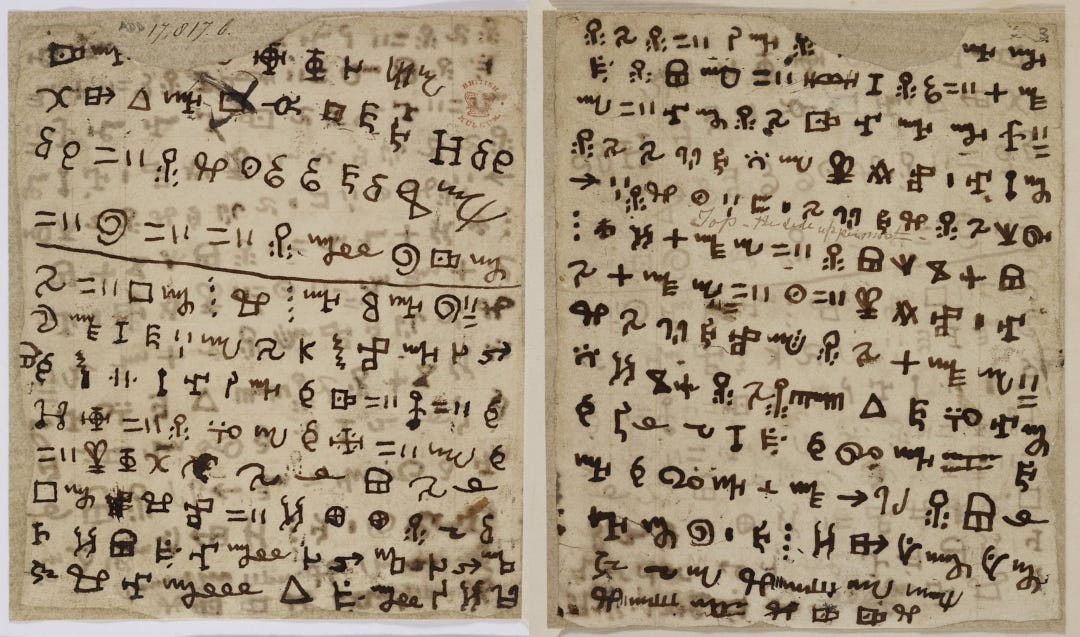

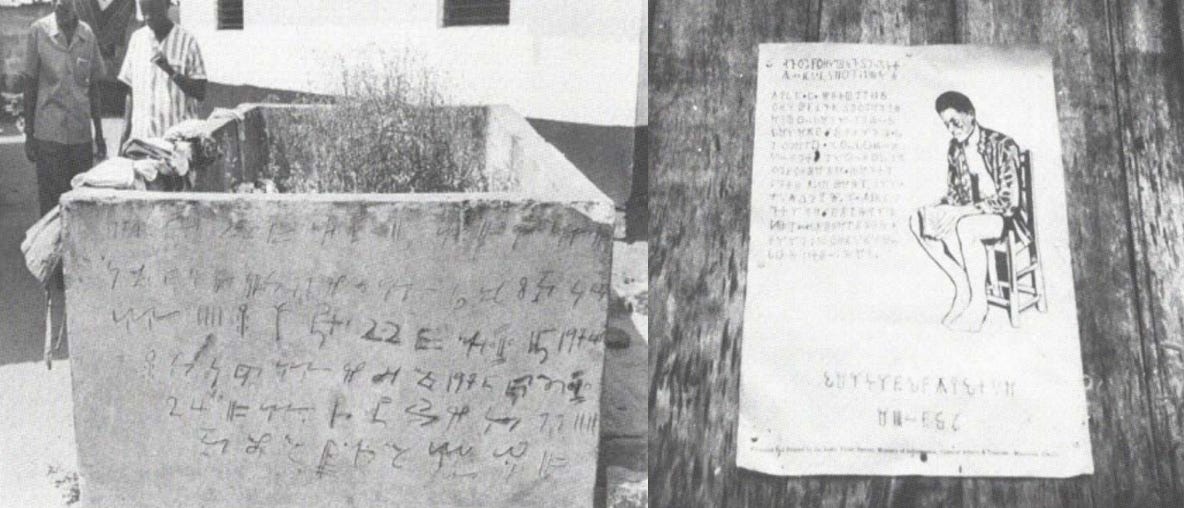

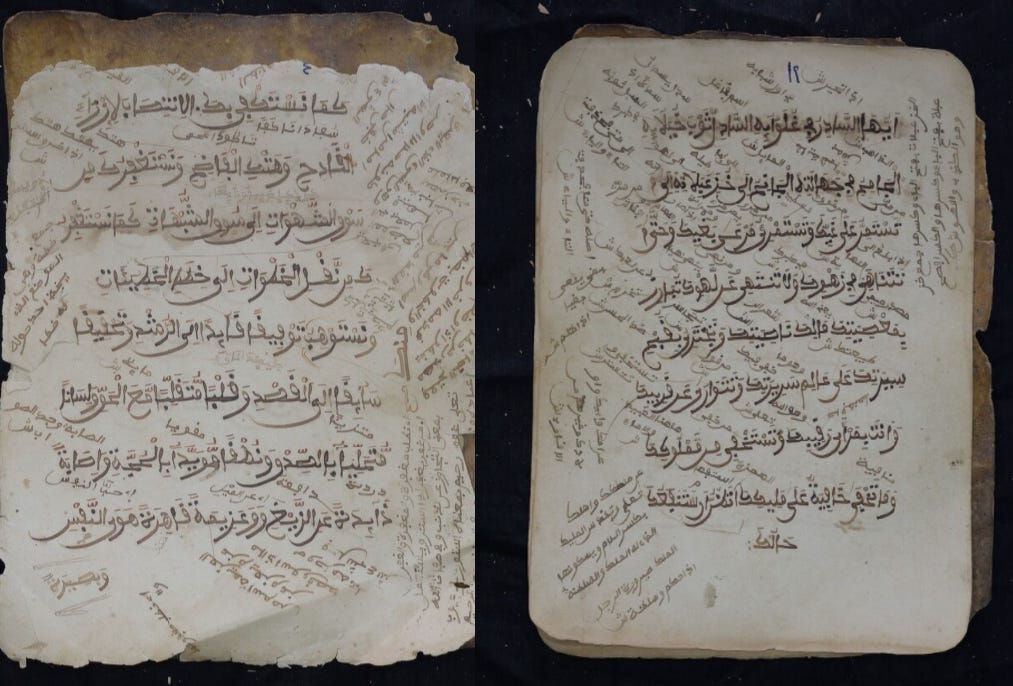

_Folio from the ‘Shukr al-Wahib fi-ma Khassana min al-'ulum’ from a private collection in Maiurno, Sudan_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!PkJB!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2cd286c4-370e-49ae-addc-9664723e7156_452x593.png)

* * *

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

* * *

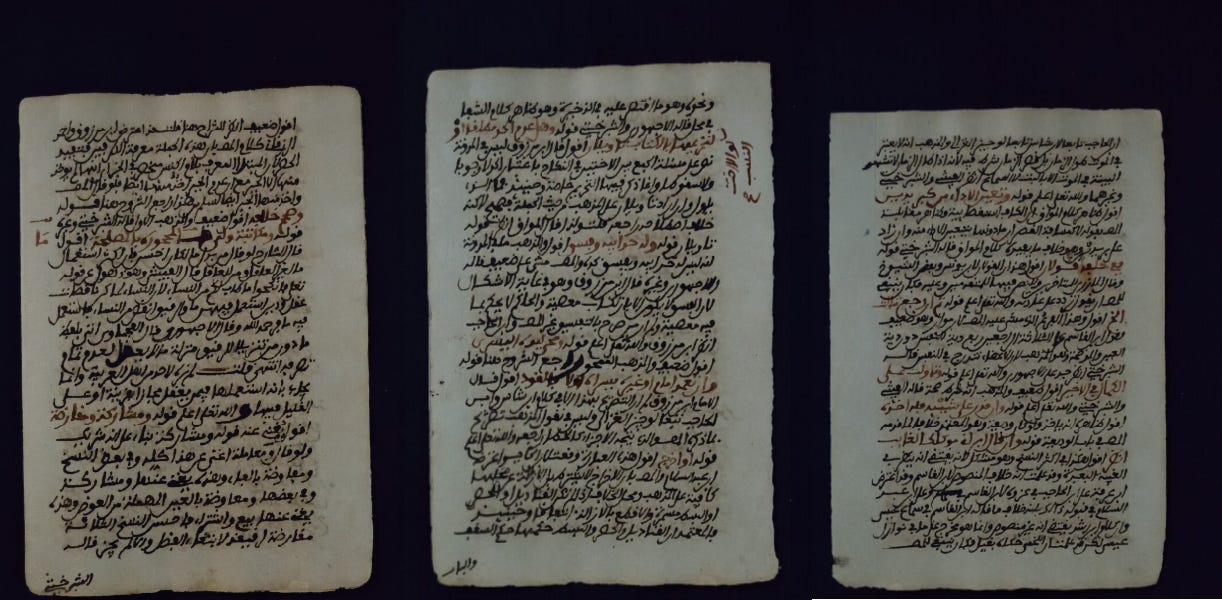

**Dan Tafa’s writings**

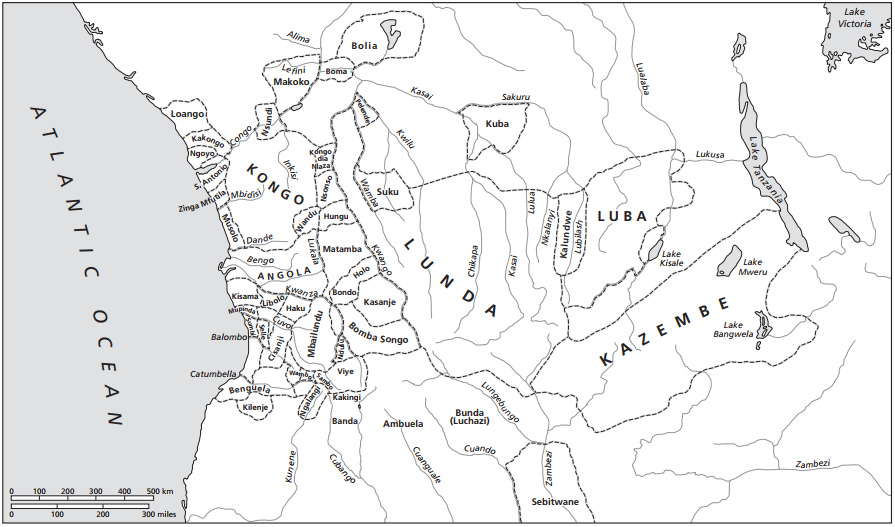

Dan Tafa wrote on a wide range of subjects and at least 72 of his works are listed in John Hunwick's “_Arabic Literature of Africa vol.2_” catalogue (from pgs 222-230) .His most notable works are on history, for which he is best remembered, especially the‘_Rawdat al-afkar_’ (The Sweet Meadows of Contemplation) written in 1824 and the ‘_Mawsufat al-sudan_’ (Description of the black lands) written in 1864; both of which include a fairly detailed account on the history of west Africa, he also wrote works on geography such as the‘_Qataif al-jinan’_ (The Fruits of the Heart in Reflection about the Sudanese Earth (world)"[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-8-42388787) which included a very detailed account of the topography, states, history and culture of west Africa and the Maghreb, and even more notably, he wrote _‘Jawāb min 'Abd al-Qādir al-Turudi ilā Nūh b. al-Tâhir’_ (Abd al-Qādir al-Turūdī's response to Nüh b. alTāhir); a meticulous refutation of the _Risāla_ of Nuh Al-Tahir, in which the latter, who is described as "the doppelgänger of Dan Tafa in the Ḥamdallāhi empire", was trying to legitimize the status of Ḥamdallāhi’s ruler Ahmad Lobbo, as the prophesied "12th caliph" by heavily altering the _Tārīkh al-fattāsh_; a famous 17th century Timbuktu chronicle on west African history[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-9-42388787).

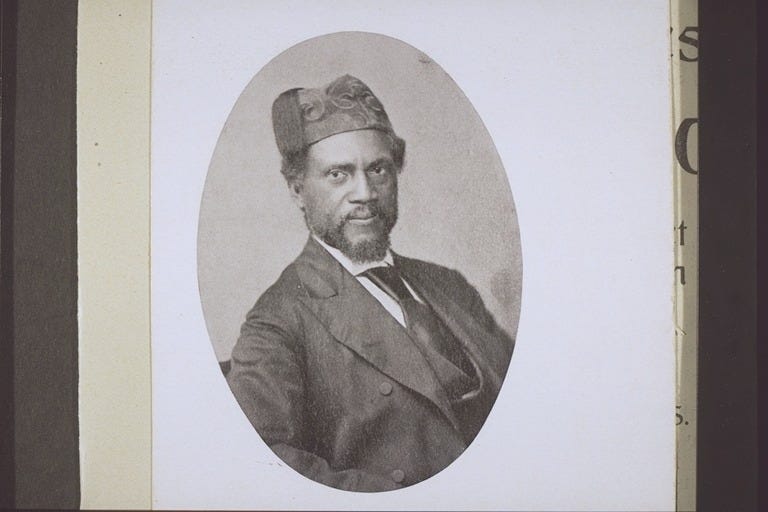

Dan Tafa had thus established himself as the most prominent and prolific writer and thinker of Sokoto such that by the time of German explorer Heinrich Barth's visit to Sokoto in 1853, Dan Tafa was considered by his peers and Barth as:

"the most learned of the present generations of the inhabitants of Sokoto… The man was Abde Kader dan Tafa …on whose stores of knowledge I drew eagerly"[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-10-42388787)

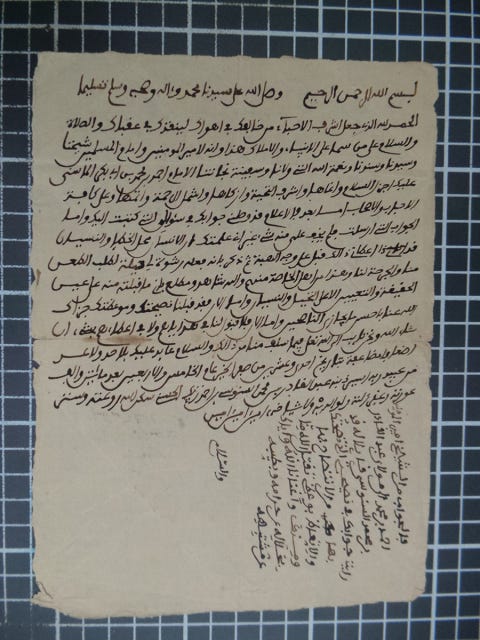

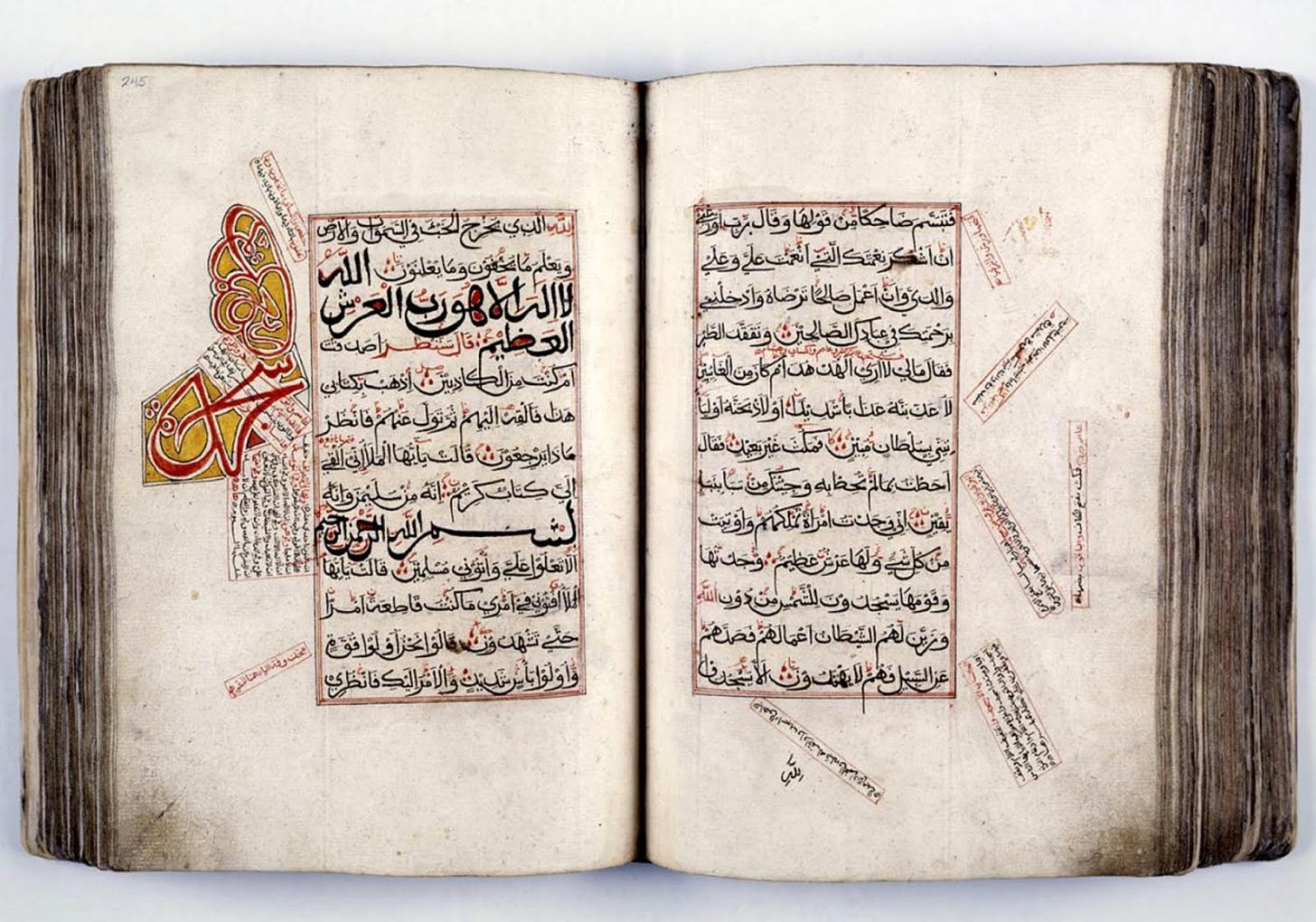

_Folio in the ‘Rawdat al-afkar’, from a private collection in Maiurno, Sudan_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ylvO!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F023b7073-56e6-41b9-9449-489ab3c7f8f1_485x623.png)

_Folio in the ‘Mawsufat al-sudan’, from a private collection in Maiurno, Sudan_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!V-Kr!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa7b4ee12-69a0-4863-8a23-8dcbe10a418c_547x775.png)

* * *

[free subscription](https://isaacsamuel.substack.com/subscribe?)

* * *

**The Philosophical writings of Dan Tafa**

Above all else, it was his writings on philosophy that set him apart from the rest of his peers; in 1828 he wrote first philosophical work titled '_Al-Futuhat al-rabbaniyya_' (The divine Unveilings) described by historian Muhammad Kani as: "a critical evaluation of the materialists, naturalists and physicists' perception of life … matters relating to the transient nature of the world, existence or non-existence of the spirit, and the nature of celestial spheres, are critically examined in the work"[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-11-42388787)

He followed this up with another philosophical work titled '_Kulliyāt al-‘ālam al-sitta_' ('The Sixth World Faculty) that is described by professor Oludamini as: "a brief but dense philosophical poem about the origins, development, resurrection, and end of the body, soul, and spirit, as well as a discussion of _hyle_ (prime matter)"[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-12-42388787) and later in his life, he wrote the'_Uhud wa-mawāthiq_ (Covenants and Treaties) in 1855. which is a short treatise written in a series of 17 oaths taken by the author, its described by Muhammad Kani as: "an apologia to his critics among the orthodox scholars who viewed philosophy with skepticism"[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-13-42388787).

According to Muhammad Kani and John Hunwick, these three works fit squarely within the genre called Falsafa ie; Islamic philosophy. Falsafa isn't to be understood as a philosophy directly coming out of Islam but rather one that was built upon centuries of various philosophical traditions including Greek, Roman, Persian philosophy[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-14-42388787) and Quranic traditions. Practitioners of Falsafa include the famed Islamic golden age philosophers such as Ibn sina (d. 1037AD), Ibn Arabi (d. 1240AD) and Athīr al-dīn Abharī(d. 1265AD) ; especially the latter two, whose work is echoed in Dan Tafa's "sixth world faculty". Dan Tafa's general philosophy can be read mostly from his two of his works ie; his last work; "covenants and treaties" which was written both in defense of philosophy and religion but also outlines his personal philosophies and ethics. and his second work; “On the sixth world faculty”.

_folio from ‘Uhud wa-mawāthiq’ (covenants and treaties) from a private collection in Maiurno, Sudan_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!2dp6!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5db2f650-ab91-401f-8706-9f865b56d7c9_490x643.png)

**1: On "covenants and treaties” : philosophy's place in the wider Muslim world and Sokoto in particular**

In the few centuries after establishing the "house of wisdom" in which Arabic translations of classical philosophical texts were stored, read and interpreted, Muslim political and religious authorities were faced with a dilemma of how to welcome the 'pagan' intellectual traditions of these texts into the ‘_ulum uid-dın’_ ( ‘‘sciences of the religion’’) where Islamic wisdom was meant to be sought and realized[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-15-42388787), a dilemma they seem to have resolved by the 12th century when Falsafa was integrated with the disciplines of theology (_Kalam)_ and Sufism (_Tasawwuf_) but the disputes and tension regarding the permissiveness of a number of 'sciences' meant that philosophy wasn't always part of the curriculum of schools both in the Islamic heartlands and in west Africa; which made the method of learning it almost as exclusive as that of the "esoteric" sciences that Dan Tafa asserted that he learned, this "exclusive" method of tutoring philosophy students was apparently the standard method of learning the discipline in Sokoto and it was likely how his uncle Muḥammad Sanbu taught it to him, even though Dan Tafa implied In his oaths that he had been teaching it to his students at his school in Salame.

The integration of philosophy and theology in Islam however, was in contrast to western Europe where philosophy and theology drifted apart during the same period[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-16-42388787) although there were exceptions to this rule, as even the enlightenment-era philosophers included "defenders of Christianity/religion" such as German philosopher Friedrich Hegel; a contemporary of Dan Tafa.

It is within this context of the tension surrounding the permissiveness of philosophy that Dan Tafa wrote his apologia. In it, he unequivocally states his adherence to his faith while also lauding the necessity of reason; for example in his **1st oath**, seemingly in direct response to his critics who likely charged him with choosing rational proofs as his new doctrine, he explains that:

_**"The evidences of reason are limited to establishing the existence of an incomprehensible deity and that Its attributes are such and such. But the evidences of reason cannot fathom in any way Its essential reality"**_

therefore he says:

_**"I have taken an oath of covenant to construct my doctrine of belief upon the verses of the Qur’an and not upon evidences of reason or the theories of scholastic theology"**_[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-17-42388787)

He then “moderates” the above oath, writing in the **2nd oath** that:

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant to closely reflect upon the established precepts and researched theories regarding the majority of existing things and upon what emerges from the influences which some parts of existence have upon others. I have not disregarded the benefits and blessings which are in these precepts. Further, I have refrained from being like the mentally shallow who say that created existence has no effective influence, whatsoever. In holding this position, I remain completely acquainted with the fundamental Divine realities from which all things have emerged."**_[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-18-42388787)

The **1st oath** was likely influenced by Uthman Fodio defense of _taqlīd_, while his argument that rational proofs alone can't reveal the existence of God was similar to the one stated by Ibn Arabi (d. 1240) in which the latter writes "If we had remained with our rational proofs – which, in the opinion of the rational thinkers, establish knowledge of God’s essence, showing that “He is not like this” and “not like that” – no created thing would ever have loved God. But the tongues of the religions gave a divine report saying that “He is like this” and “He is like that”, mentioning affairs which outwardly contradict rational proofs". And the **2nd oath**, while not contradicting the first, leaves plenty of room for Dan Tafa to consider "researched theories" on the things in nature without disregarding the befits in their principles

He continues with this moderation in the **3rd oath** by implying that there is no contradiction between the proofs of reason and the authority of the Qu'ran, writing that:

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant to weigh and measure all that I possess of comprehension with the verses of the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet …Whoever doubts this, then let him try me"**_

in this oath, Dan Tafa defends his knowledge and use of philosophy stating that he weighs it with his faith and is steadfast in both, so much that he invites anyone among his peers to an intellectual debate if they wish to challenge him on both. This oath is also related to the **9th oath** in which he writes:

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant to closely consider the established principles which underline worldly customs. For, these principles are an impregnable mainstay in knowing the descent of worldly affairs, because these affairs descend in accordance with these principles"**_

the worldly customs here being a reference to practices that are outside the Islamic law which aren't concerned with worship eg the study of philosophy and esoteric sciences which are the subject of this work.

Dan Tafa also takes care not to offer the above intellectual debate (of the **3rd oath**) on account of his own pride (…"let him try me") but rather in good faith, as he also writes in his**4th oath:**

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant that I will not face off or contend with anyone in a way in which that person may dislike; even when the bad character of the individual requires me to. For, contending with others in ways that are reprehensible is too repugnant and harmful to enumerate. This oath is extremely difficult to uphold, so may Allah assist us to fulfill it by means of His benevolence and kindness."**_

In this apologia, Dan Tafa however seemingly yields to his critics by promising to end his teaching of philosophy, leaving no doubt he was tutoring some of his students in Salame the discipline of Falsafa, as he writes in his **10th oath:**

_**"I have taken and oath and covenant not to invite anyone from the people to what I have learned from the philosophical (**falsafa**) and elemental sciences; even though I took these sciences in a sound manner, rejecting from that what is in these sciences of errors. Along with that, I will not teach these sciences to anyone in order that they may not be led astray; and errors will thus revert back to me"**_

this was the first explicit mention of _falsafa_ in these oaths but it was certainly the main subject of this apologia. In this oath, he promises to refrain from teaching philosophy to his students to prevent them from being led into error that would revert back to him, he nevertheless continues defending his education in philosophy writing that he took it "in a sound manner".

In his oaths he also includes ethical concerns that were guided by his personal philosophy for example in his **7th oath** he writes that":

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant to not compete with anyone in a right which that person has a greater right over than me. Rather, I will stop with the fundamental right which is mine until it is they who compete with me in my right. Then at that point, I will contend with them with the truth for the truth regardless if that right of mine is of a religious or worldly nature. Realize that the prerequisites for reclaiming and demanding one’s rights is well known with the masters of the art of disposal"**_

The above oath could be seen in practice when a promise made to Dan Tafa's by the Sokoto ruler Ali Ibn Bello (r. 1842 to 1859) to make Dan Tafa the _Wazir_, was instead passed on to another, but Dan Tafa continued advising Ali Ibn Bello despite the latter breaking his promise to give him the _Wazir_ office which he, more than anyone else, was fully qualified for, and all this happened in 1859, after he had written this work[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-19-42388787)

And in his **8th oath** he writes:

_**"I have taken an oath and covenant not to take two distinct causative factors or more in seeking after my worldly affairs. Rather, I will stop with a single cause and will not add any additional causative factors until the one I relied upon fails. Then I will change to another causative factor for earning wealth. This is mainly in order not to make things constricted for other Muslims in their causative factors"**_

This could also be seen in practice at the educational institution that Dan Tafa operated which continued to be his primary source of income, and from where he continued writing books, advising _Amirs_ and teaching his students. He also devised an exam to test the leaning standards of the Sokoto scholars that consisted of cunning historical and legal questions, many of his works contain critiques and recommendations on how various disciplines should be studied and taught[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-20-42388787)

* * *

**2: “On the sixth world faculty”: the development of intellect and prime matter**

"oaths an covenants" is in part, a summary of his earlier philosophical works especially the one titled "on the sixth world faculty" in which he writes on the development of intellect:

_**"On the Development of the Intellect:**_

_**The development of intellects is by firm patience Its striving in actions …**_

_**It brings news of all matters, And seeks to clarify what is required and what is supererogatory for them**_

_**And it holds your soul back from its lusts, And eliminates aggression to prevent injuries"**_

He continues …

_**"On prime matter:**_

_**The [prime] matter is the fixed entities Before their attributes are qualified by existence**_

_**And the continuous rain (dīma) is like the soul, from it arises Warmth with coolness, and they spread**_

_**And so follows wetness and dryness And the rest of four basic elements Then appear the spheres and the planets Orbiting them, and likewise the fixed stars**_

_**The motions perpetually traverse the spheres Running with darkness and illuminating the kingdom (al-mulk)**_

_**Then from them appear the engendered beings [the kingdoms] Which are multiple and composite Like the mineral, plant, and animal [kingdoms]**_

_**They differ in their governing principle From**_ _**which they become hot and dry [fire], cold and wet [water] And the inverse of these concomitants occurs [hot and wet (air), cold and dry (earth)] In accordance with natural transformation At the places of land and sea**_

_**As for animals, their nature is different …**_ (continued)"[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-21-42388787)

The above excerpt is from the "sixth world faculty" as translated by Oludamini, who describes the who work as "characterized by a density and concision that seems to necessitate an oral commentary". Dan Tafa's philosophy on prime matter can also be analyzed through the Avicenna and Aristotelian philosophies of prime matter (Hylomorphism)

**Dan Tafa’s writings of Philosophical Sufism**

also included among his writings are those termed "Sufi philosophies", and they include works such as '_Nasab al-mawjūdāt_' (Origin of Existents) which describes the origin of each existent thing in terms of its essence, its attributes, its governing principle (_nāmūs_), and its nature. And another work titled '_Muqaddima fī’l-‘ilm al-marā‘ī wa ta‘bīr_' which is an introduction to the science of dreams and their interpretation from the perspective of both natural philosophy and philosophical Sufism, and other works like the '_Muqaddima fī’l-‘ilm al-marā‘ī wa ta‘bīr_', '_Naẓm al-qawānīn al-wujūd_', etc.

* * *

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

* * *

**The rest of Dan Tafa’s works**

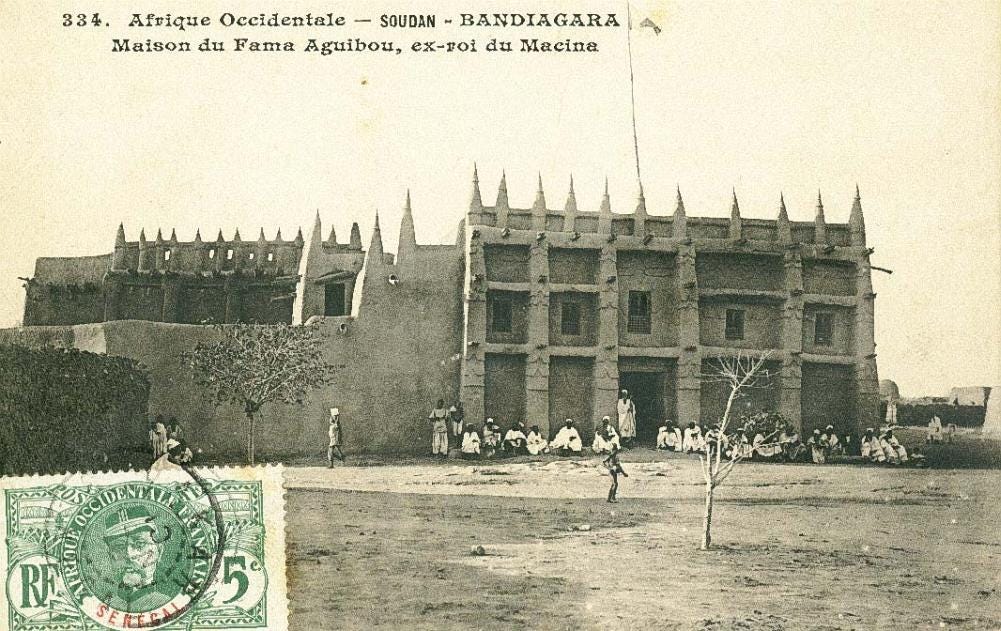

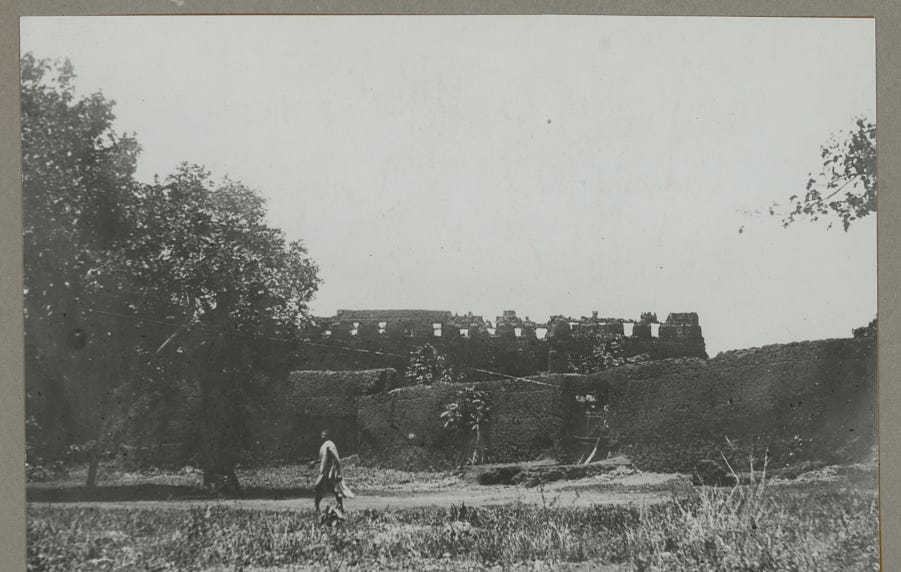

Unfortunately, in 1898, during France’s African colonial wars, the Voulet–Chanoine military expedition (which was a very notorious and scandalous campaign even for the time), the French soldiers, who were passing through northern Sokoto, “burning and sacking as they went”, also invaded and burned Salame to the ground[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-22-42388787), "and took away with them valuable books"[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-23-42388787) what survived of Dan Tafa’s large library and school were these 72 works, 44 of which are in the private collection of his son; Shakyh Bello ibn Abd’r-Raazqid, which is currently in Maiurno, Sudan[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-24-42388787)

_Folio from ‘Nasab al-mawjūdāt’, from a private collection in Maiurno, Sudan_

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!E76W!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F45e989e7-37d4-4036-9217-167a3b2f264e_449x606.png)

**Conclusion**

As the works of Dan Tafa demonstrate, Sokoto was home to a robust system of education during west Africa's intellectual zenith that included a vibrant tradition of Falsafa (philosophy) and various sciences, this tradition was similar to that in contemporaneous centers of learning in the Muslim world. While it's unclear to whom these philosophical works were addressed, the nature of his writing suggests they were addressed to his peers rather than his students although the need for oral commentary leaves open the possibility that he taught these works in his school. Dan Tafa's apparent exceptionalism among the surviving west African philosophical writings is mostly a result of the neglect of west African literary traditions rather than an evidence of absence; for example, Dan Tafa was taught everything he knew while in Sokoto which was unlike many of his west African peers who travelled widely while studying and teaching and some went even further, eg Salih Abdallah al-Fullani from guinea whose work is known as far as Syria and India[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-25-42388787) added to this, Dan Tafa's works were only known in his region (northern Nigeria) unlike peers such as Nuh Al Tahir whose works were known in nigeria, Mali, Mauritania and the Senegambia.

Yet despite this, the wealth and depth of Dan Tafa's philosophical writings attest to the existence of a vigorous tradition of philosophy studies and discourses in west Africa including those that were transcribed into writing.

* * *

**for more on African history, please subscribe to my Patreon account**

[patreon](https://www.patreon.com/isaacsamuel64?fan_landing=true)

* * *

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-1-42388787)

Deep knowledge: Ways of Knowing in Sufism and Ifa, Two West African Intellectual Traditions, by Oludamini Ogunnaike, pgs 10-18

[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-2-42388787)

Ethiopian philosophy vol3, by claude sumner

[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-3-42388787)

The Life of Shaykh Dan Tafa by Muhammad Shareef, pg 28

[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-4-42388787)

Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of central Sudanic Africa Vol.2, by John Hunwick, pg 161

[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-5-42388787)

John Hunwick, pg 162

[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-6-42388787)

Muhammad Shareef pg 31

[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-7-42388787)

Philosophical Sufism in the Sokoto Caliphate: The Case of Shaykh Dan Tafa by Oludamini Ogunnaike, pg 141, in ‘Islamic Scholarship in Africa: New Directions and Global Contexts’

[8](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-8-42388787)

A Geography of Jihad. Jihadist Concepts of Space and Sokoto Warfare by Stephanie Zehnle pg 85-101

[9](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-9-42388787)

the Tārīkh al-fattāsh at work; A Sokoto Answer to Ḥamdallāhi's Claims, pg 218-222 in Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith

[10](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-10-42388787)

Henrich Barth, travels vol iv, pg 101

[11](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-11-42388787)

John Hunwick, pg 222

[12](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-12-42388787)

Philosophical Sufism by Oludamini Ogunnaike pg 152

[13](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-13-42388787)

John Hunwick pg 230.

[14](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-14-42388787)

Precolonial African Philosophy in Arabic by Souleymane Diagne, pg 67 of “A Companion to African Philosophy”

[15](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-15-42388787)

Souleymane Diagne, pg 68

[16](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-16-42388787)

Deep knowledge by Oludamini Ogunnaike, pg 6

[17](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-17-42388787)

Philosophical Sufism by Oludamini Ogunnaike pg 150

[18](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-18-42388787)

muhammad shareef's translation

[19](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-19-42388787)

The Life of Shaykh Dan Tafa by Muhammad Shareef pg 46

[20](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-20-42388787)

Muhammad Shareef pg 46

[21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-21-42388787)

philsophical sufism by Oludamini Ogunnaike pg 168)

[22](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-22-42388787)

The sokoto caliphate by murray last pg 140)

[23](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-23-42388787)

Literature, History and Identity in Northern Nigeria by Tsiga, et al. pg 26

[24](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-24-42388787)

The Life of Shaykh Dan Tafa by Muhammad Shareef pg 50

[25](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher#footnote-anchor-25-42388787)

Arabic Literature of Africa: Writings of Western Sudanic Africa vol4 by John Hunwick pg 504-5

[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email&utm_content=share&action=share)

* * *

#### Subscribe to African History Extra

By isaac Samuel · Launched 4 years ago

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

[](https://substack.com/profile/390471965-thegonlin)

[5 Likes](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-19th-century-african-philosopher)

[](https://substack.com/note/p-42388787/restacks?utm_source=substack&utm_content=facepile-restacks)

5

Share

#### Discussion about this post

Comments Restacks

Top Latest Discussions

[Acemoglu in Kongo: a critique of 'Why Nations Fail' and its wilful ignorance of African history.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

[There aren’t many Africans on the list of Nobel laureates, nor does research on African societies show up in the selection committees of Stockholm.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

Nov 3, 2024•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

111

26

26

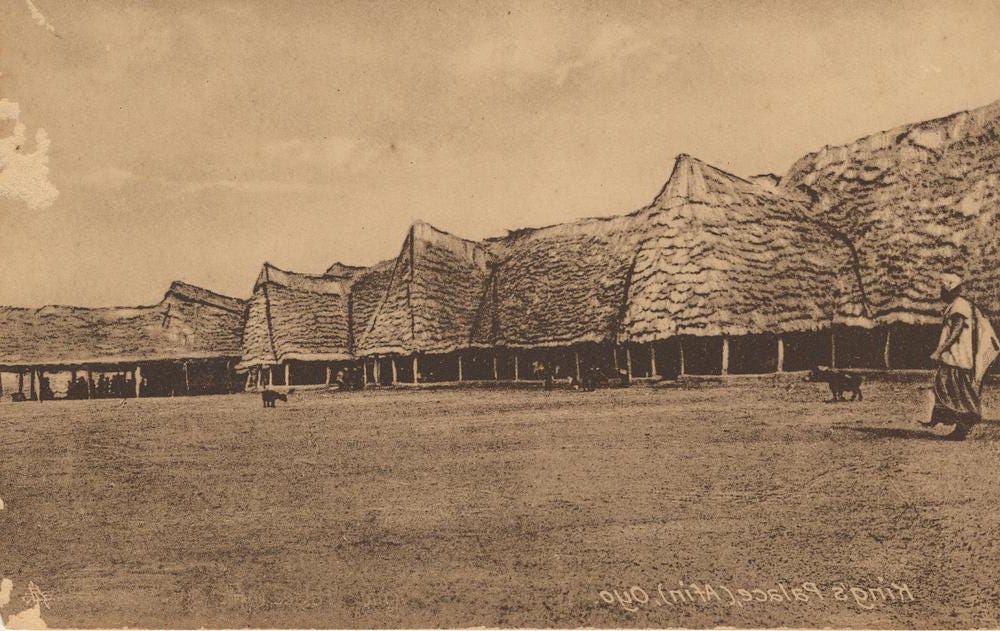

[The city states of the Yoruba: a history of pre-colonial West African urbanism (1000-1900 CE)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

[At the close of the 19th century, the Yorùbá region of South-west Nigeria was one of the most urbanized places in Africa.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

Sep 7, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

59

6

8

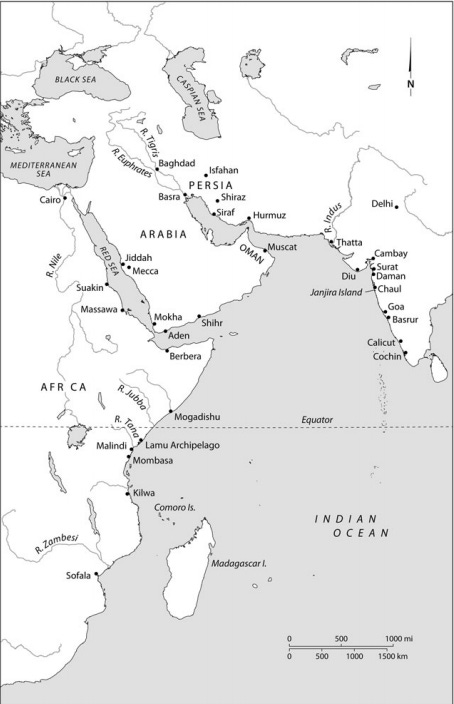

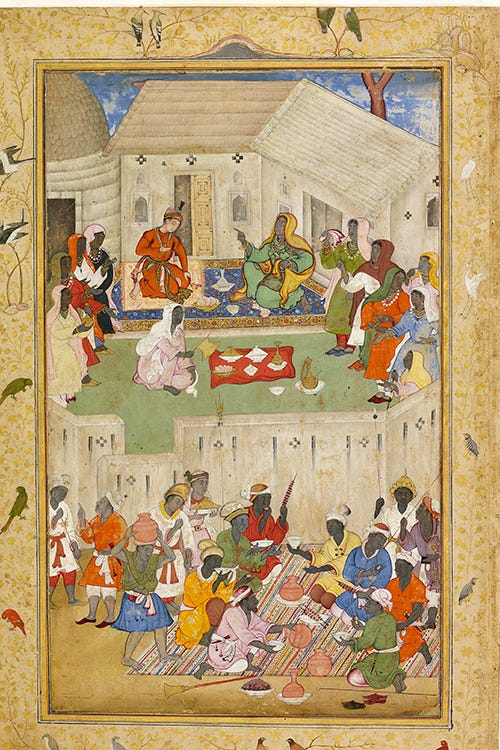

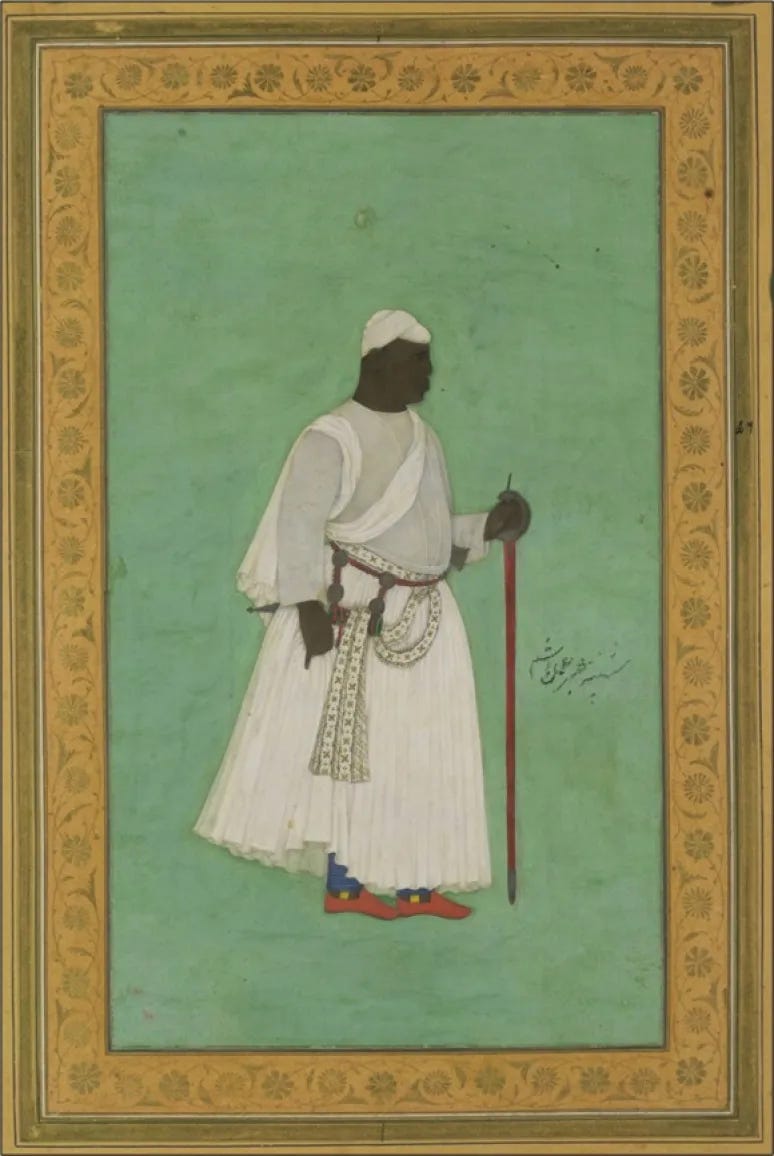

[Africans in the Indian Ocean world and the autobiography of a Somali Globetrotter.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

[In 1944, a soldier on Australia’s most remote northern coastline discovered a handful of copper coins that were originally minted in the medieval…](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

Aug 17, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

66

4

11

See all

### Ready for more?

Subscribe

© 2026 isaac Samuel · [Privacy](https://substack.com/privacy) ∙ [Terms](https://substack.com/tos) ∙ [Collection notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected)

[Start your Substack](https://substack.com/signup?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=web&utm_content=footer)[Get the app](https://substack.com/app/app-store-redirect?utm_campaign=app-marketing&utm_content=web-footer-button)

[Substack](https://substack.com/) is the home for great culture

|

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in

|

Published Time: 2025-12-21T18:40:22+00:00

A brief history of Christianity in Africa's Religious Traditions

===============

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

[African History Extra](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

=============================================================

Subscribe Sign in

Discover more from African History Extra

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Over 15,000 subscribers

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

Already have an account? [Sign in](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)

A brief history of Christianity in Africa's Religious Traditions

================================================================

[](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

Dec 21, 2025

62

4

9

Share

Christianity was present in Africa long before the imposition of colonial rule; however, it remained only one of several religious traditions, and despite centuries of sustained contact with Christian societies, its influence across the continent was relatively limited.

With the exception of Northern Africa, where the changes in religious affiliation were influenced by shifts in the political landscape of the Mediterranean world, most of the African continent remained under local authority. Consequently, the spread and adaptation of religious traditions were largely shaped by local rather than external actors.

Recent scholarship on African traditional belief systems has highlighted the scale, complexity, and antiquity of their cosmologies, ritual practices, and central deities.

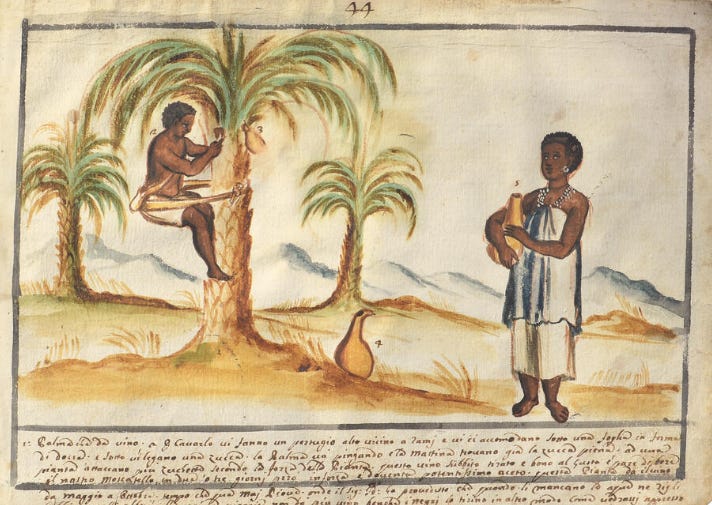

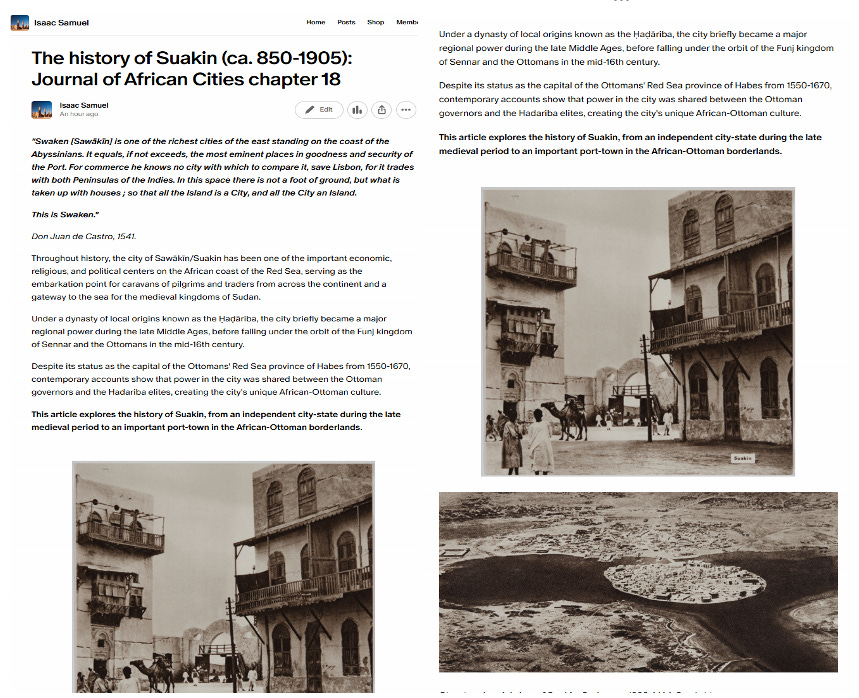

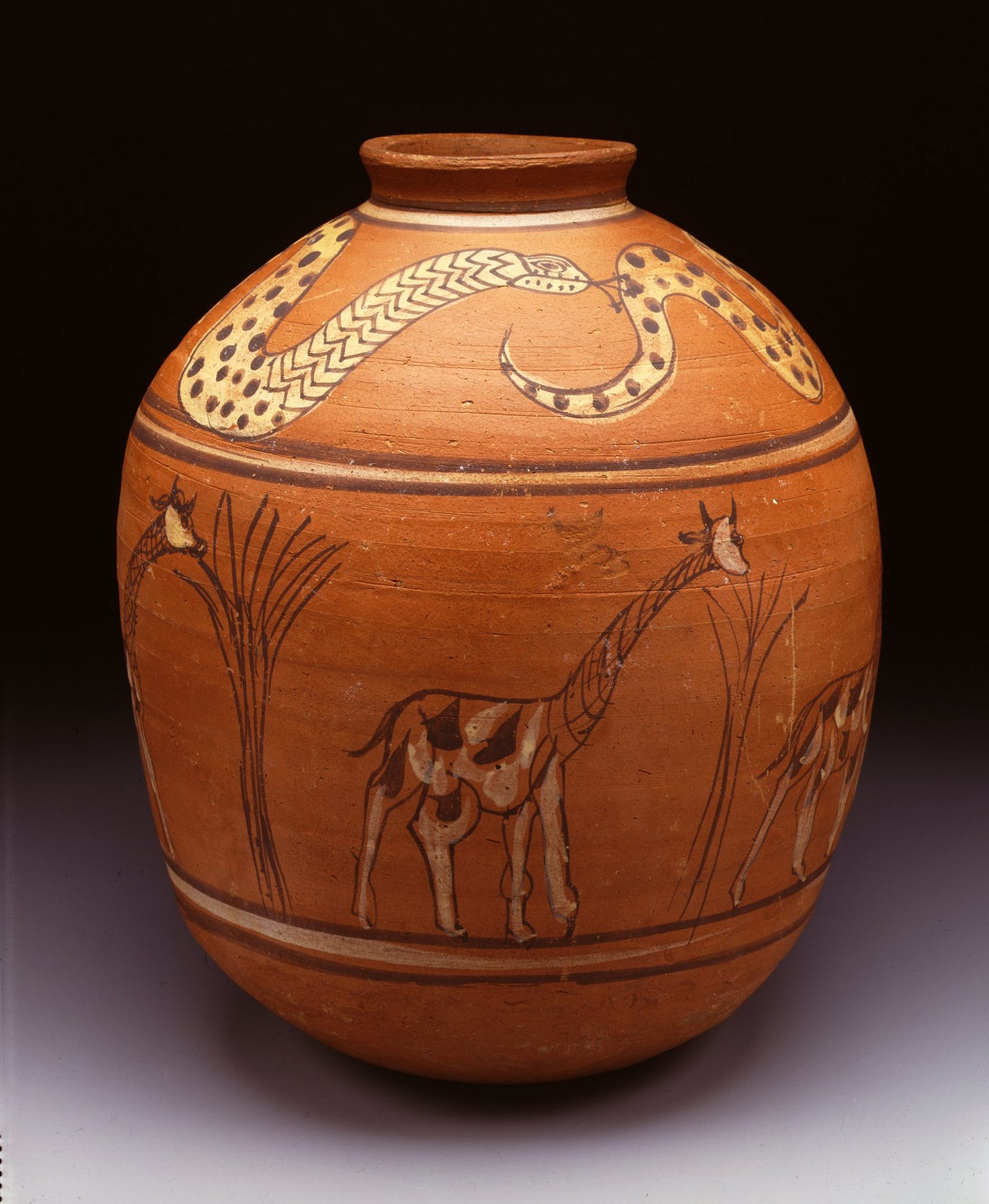

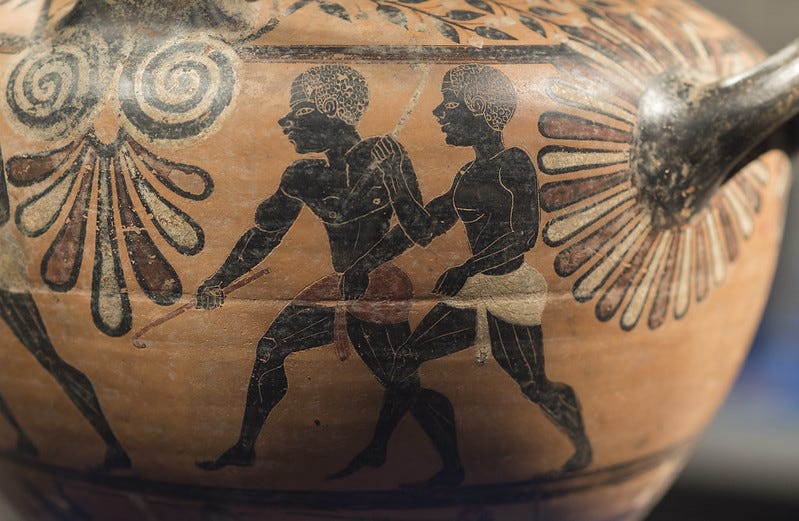

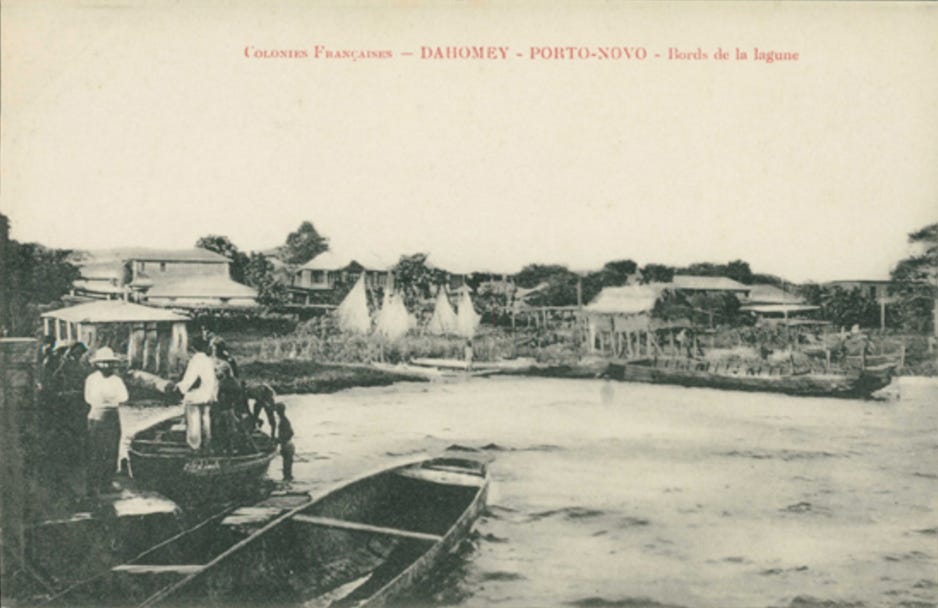

The **[rainbow-serpent deities of West Africa](https://www.patreon.com/posts/dan-and-dangbe-121284939)** and the Atlantic world, which were first documented at Ouidah (Benin) in the 17th century but likely originated in the Middle Ages, were spread by local priests across multiple kingdoms and venerated in a variety of modest temples.

In the Meroitic kingdom of Kush, religious life included the worship of the deity Isis, for whom several temples were constructed across the Nile valley. These institutions were maintained by a dedicated priestly class that played a central role in disseminating the cult of the “Mother of God” **[throughout the Roman world](https://www.patreon.com/posts/118446319)**.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3a9D!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc4539da5-e230-4958-9f10-69d627446d8b_600x420.png)

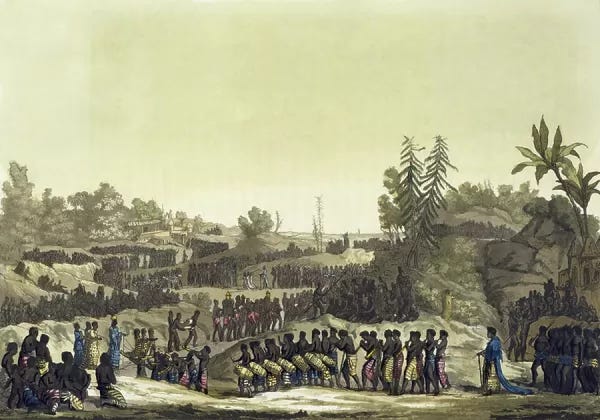

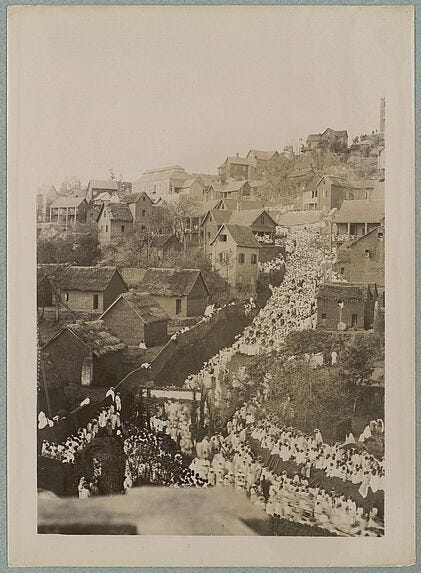

_**'Festa in onore del dio serpente' (Festival in honor of the God Snake)**_, Ouidah. 19th-century engraving by Giovanni Antonio

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!R8JL!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8b722fb5-ac63-4832-8135-5972e0a5afbe_568x503.png)

_**Amulet showing seated Isis suckling her son Horus**_. Nubian, Napatan period, 25th Dynasty, 7th century BC. Findspot: Meroe, Sudan. _**Amulet of Isis nursing the infant Horus,**_ Nubian, Meroitic Period. Findspot: Sudan, Meroe. Boston Museum.

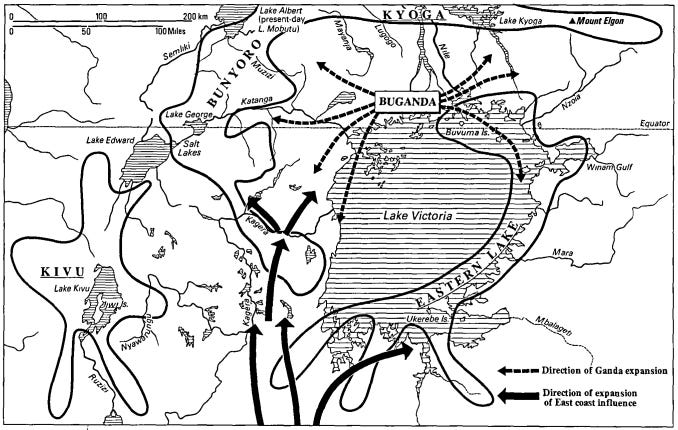

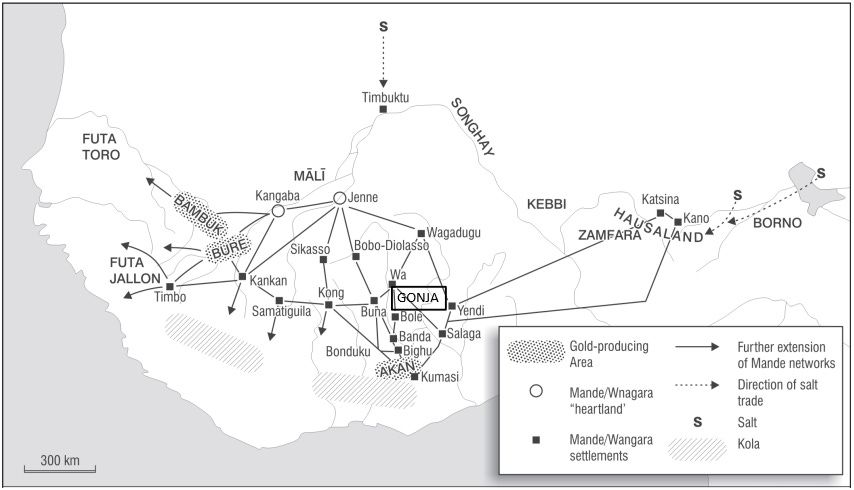

Similarly, the adoption of Islam across broad swathes of the continent is attributed to the expansion of commercial diasporas, such as [the Jabarti](https://www.patreon.com/posts/intellectual-and-97830282) in the Horn of Africa, [The Swahili](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-intellectual-history-of-east) of the East African coast, and [the Wangara](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/foundations-of-trade-and-education) of West Africa.

Christianity also flourished in this diverse religious milieu from classical antiquity through the early modern period. While earlier scholarship on classical Christianity emphasized the conversion of ‘pagan’ monarchs, more recent studies have shown that the spread of the religion was not the result of singular, transformative events but rather occurred through the gradual process of inculturation.

Inculturation refers to the adoption of Christian teachings and practices in a particular cultural context. The concept has been widely applied in studies of Christianization, not only in the Roman world but also in other ancient societies, including the kingdoms of Aksum and Nubia.

The conventional narrative of the Christianization of Aksum centers on the conversion of King Ezana in 340 CE, traditionally attributed to two Syrian captives at his court who had arrived during the reign of his predecessor, Ousanas.

However, the historian David Phillipson has argued that the adoption of Christianity in Aksum was a gradual process, “presented to the king and his diverse subjects with skill and selectivity.” Documentary evidence attests to the presence of Christians in the capital before Ezana’s conversion, while the king’s own inscriptions, initially framed in polytheistic language, suggest a cautious and incremental embrace of the new faith.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-1-182221546)

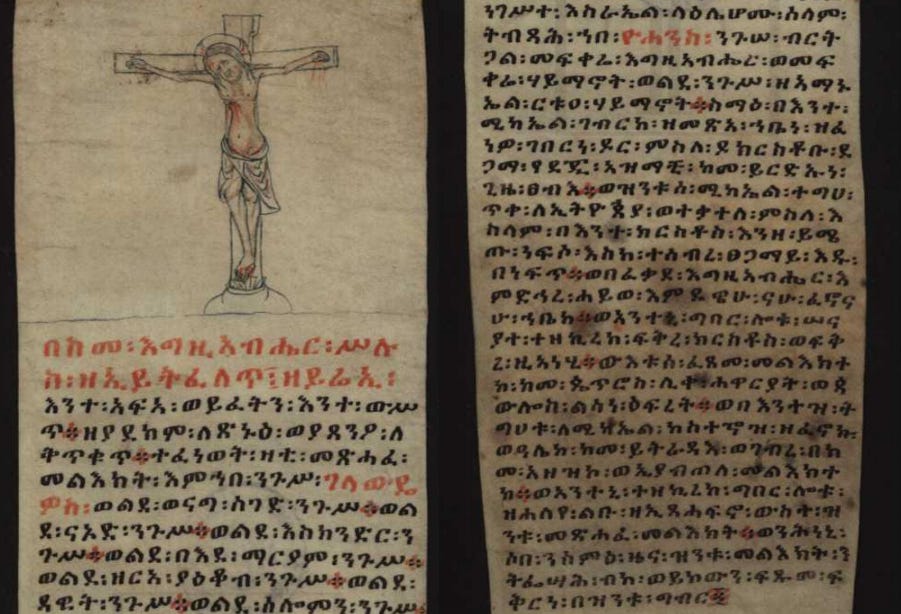

Christianity was subsequently adopted by broader segments of the population and developed a distinctly Aksumite character, which was preserved and further elaborated from the Middle Ages through the modern period by the Tewahedo Church of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!1HU4!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F78b211ad-fcdd-4e73-af76-c4bd2f5ca66a_1366x456.png)

_**The Garima Gospels**_, ca 330–650 and 530–660 CE. Tigray, Ethiopia. digitized by [the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library](https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/132897).

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ckR8!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb1a1400d-f1a4-4963-87fa-244328f81ad7_612x408.png)

_**The church of Yemrehanna Krestos, Ahmara, Ethiopia.**_

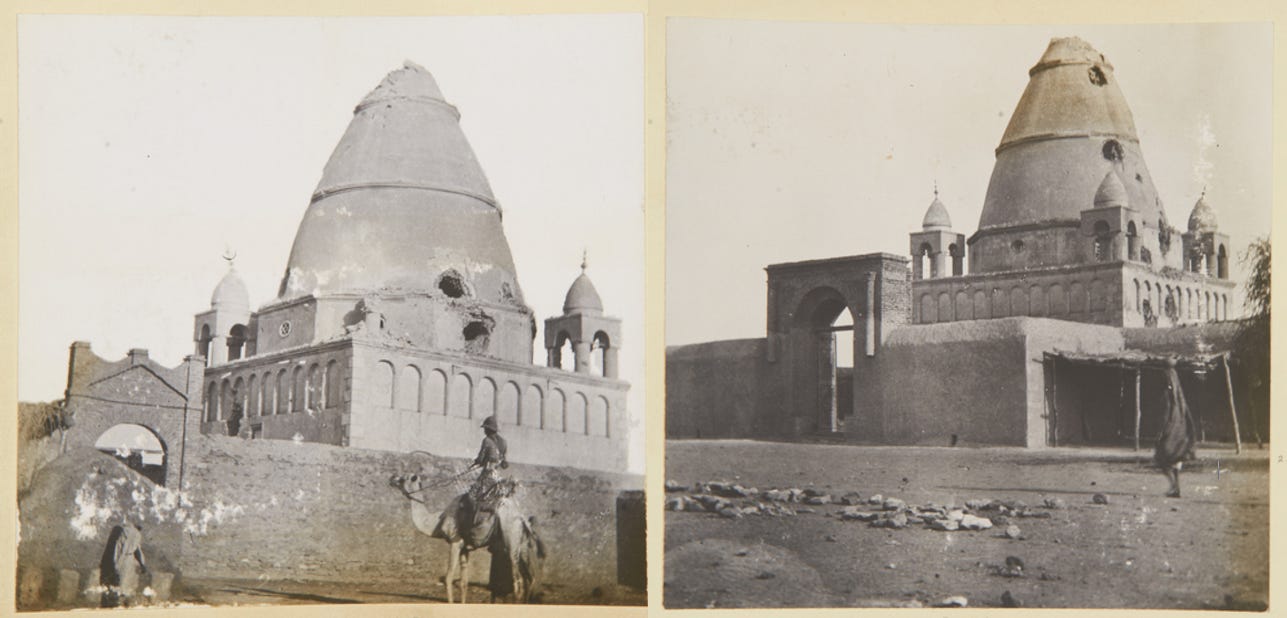

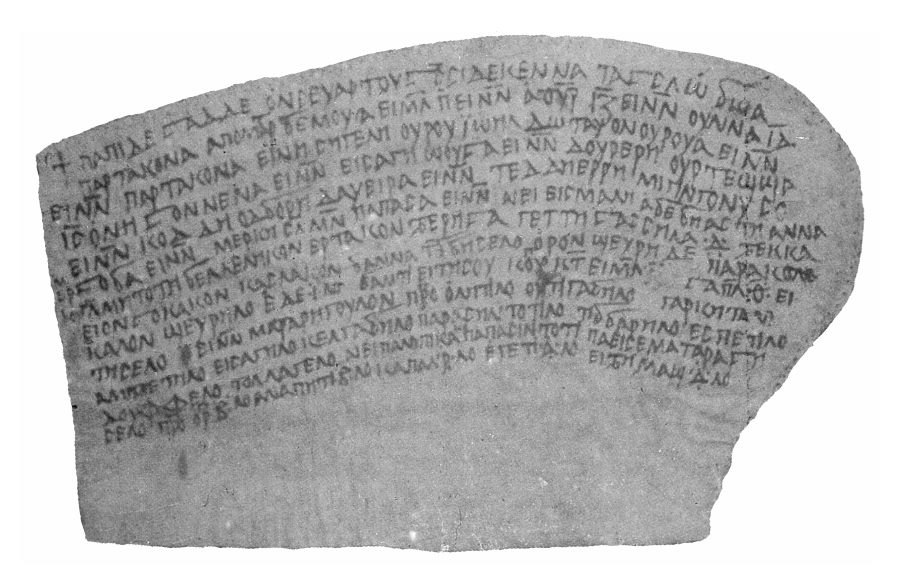

Similar to Aksum, conventional church histories attribute the foundation of Nubian Christianity to Byzantine ecclesiastical initiatives, specifically the dispatch of Melkite and Monophysite missionaries to Nubia (Sudan) by Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora in the 6th century CE.

However, archaeological and documentary evidence suggest that Christianity was present in Nubia more than a century earlier. Rulers were interred with Christian objects, and at least one prince bore a Christian name, Mouses. According to Salim Faraji, the reign of the [Noubadian](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/an-african-kingdom-on-the-edge-of?utm_source=publication-search) king Silko, whose victory inscription declares that “God gave me the victory,” laid the political and cultural foundations for the broader Christianization of Nubia.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-2-182221546)

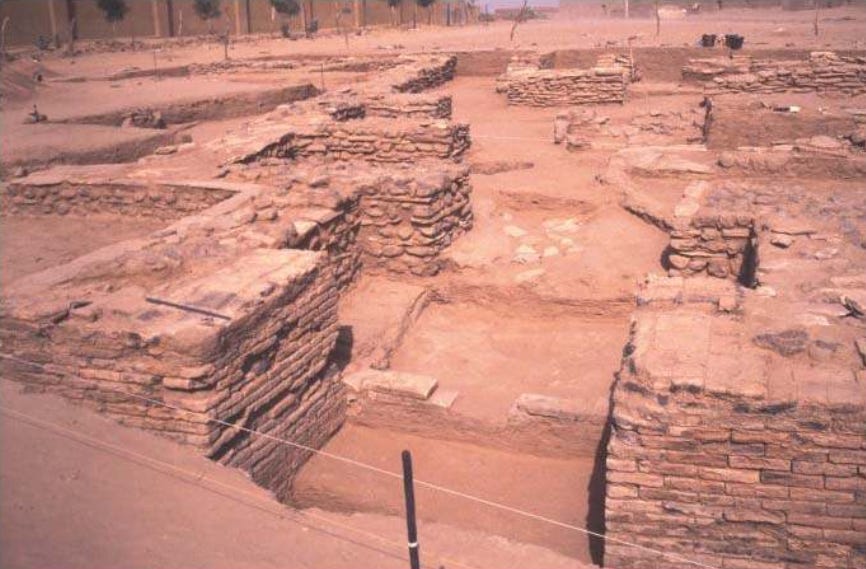

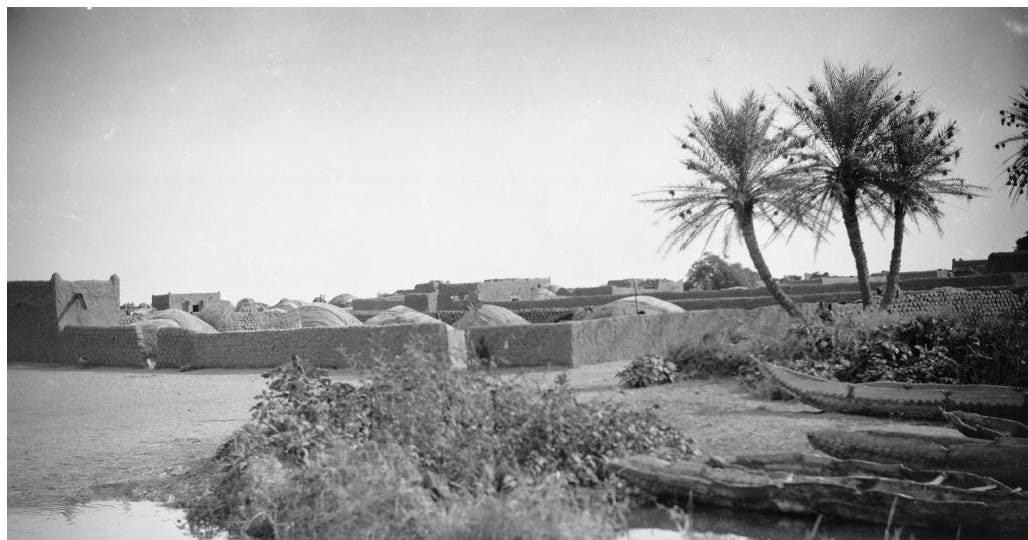

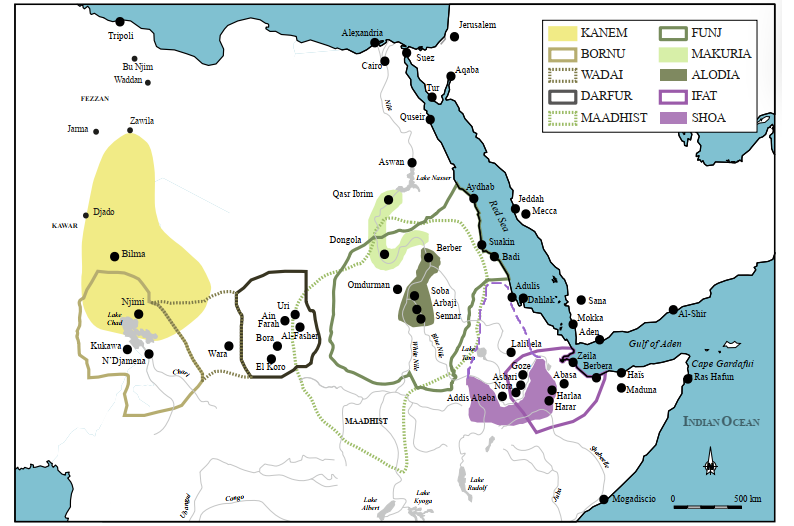

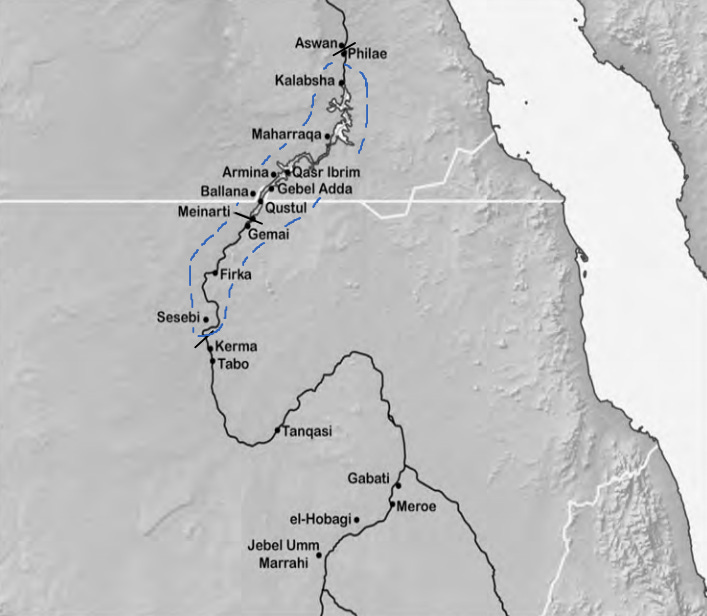

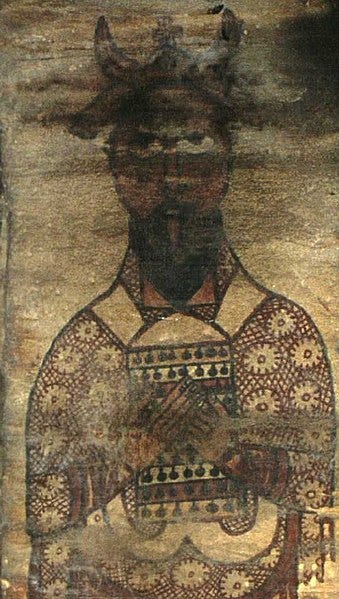

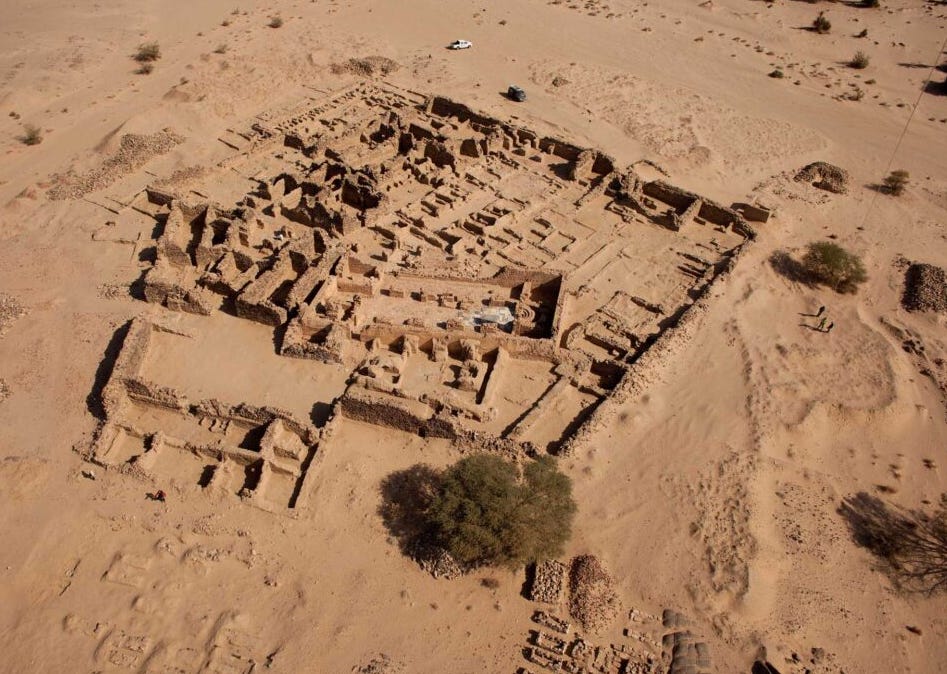

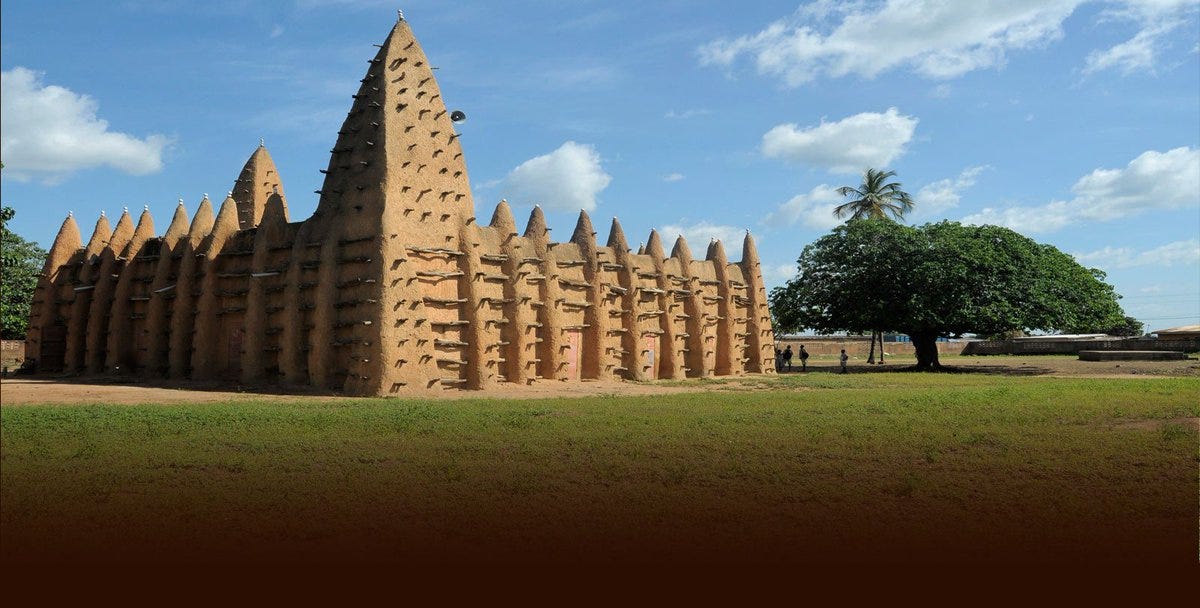

For most of the Middle Ages, from the 6th to the 14th century, Christianity flourished in the three Nubian kingdoms of Nobadia, [Makuria](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/christian-nubia-muslim-egypt-and), and Alodia, where it developed a distinctly Nubian character. Cathedrals and monasteries adorned with elaborate paintings were constructed at Dongola, Soba, and Faras, and Nubian Christian communities persisted as late as the 16th century, long after the political collapse of the three kingdoms.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!hFz5!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F092b17a2-5a86-4d7e-94a4-cc21acbb1e50_839x555.png)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!BJ4S!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Faf6cd548-aa84-4def-b7bd-fa14cd72ba20_1331x1000.jpeg)

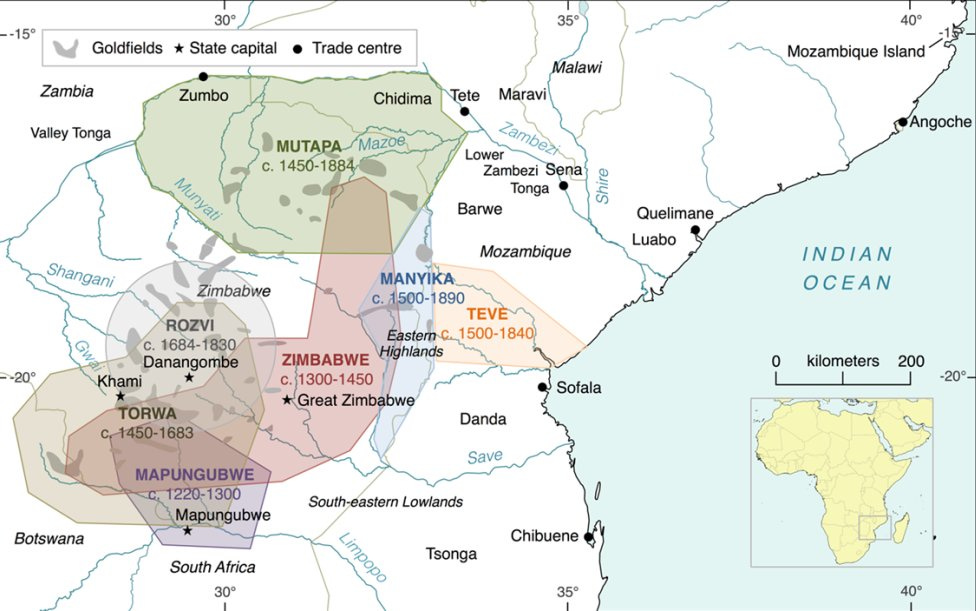

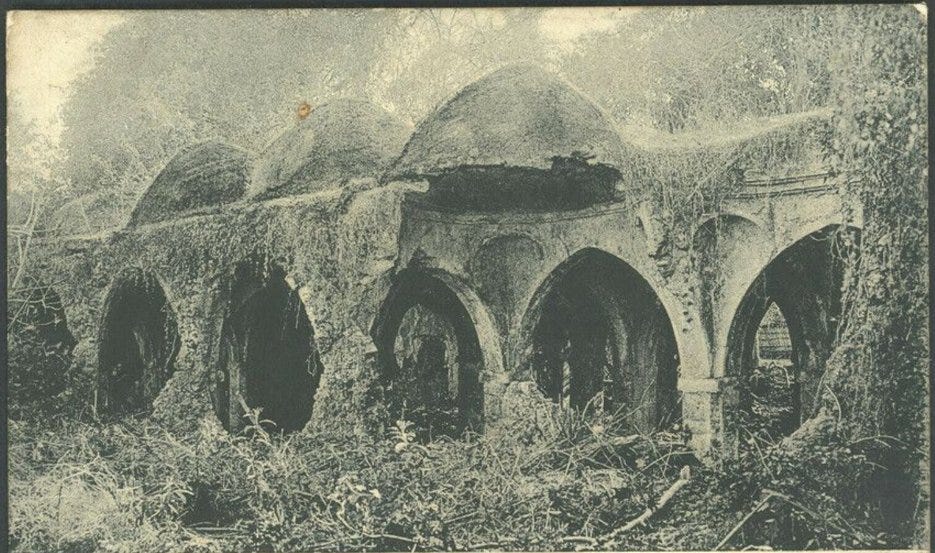

_**The medieval church of Bangnarti, Sudan.**_ image by B. Żurawski

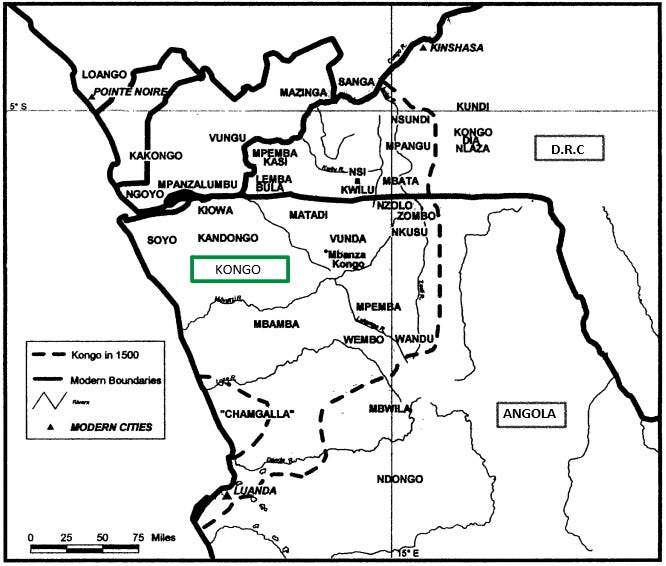

In the southern half of the continent, historical research on early Christian communities has largely focused on [the Kingdom of Kongo](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-kingdom-of-kongo-and-the-portuguese), where Christianity endured for nearly five centuries. This contrasts with other societies, such as those along the [Swahili coast](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-portuguese-and-the-swahili-from?utm_source=publication-search) (Kenya, Tanzania), [Mutapa (Zimbabwe)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-kingdom-of-mutapa-and-the-portuguese), and [Ndongo](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-kingdom-of-ndongo-and-the-portuguese?utm_source=publication-search) (Angola), where the religion largely disappeared shortly after its introduction in the 16th century.

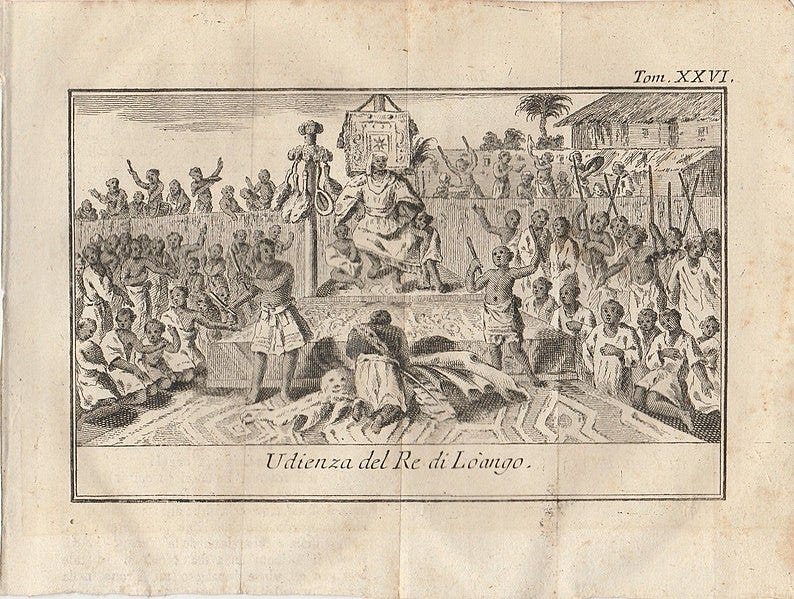

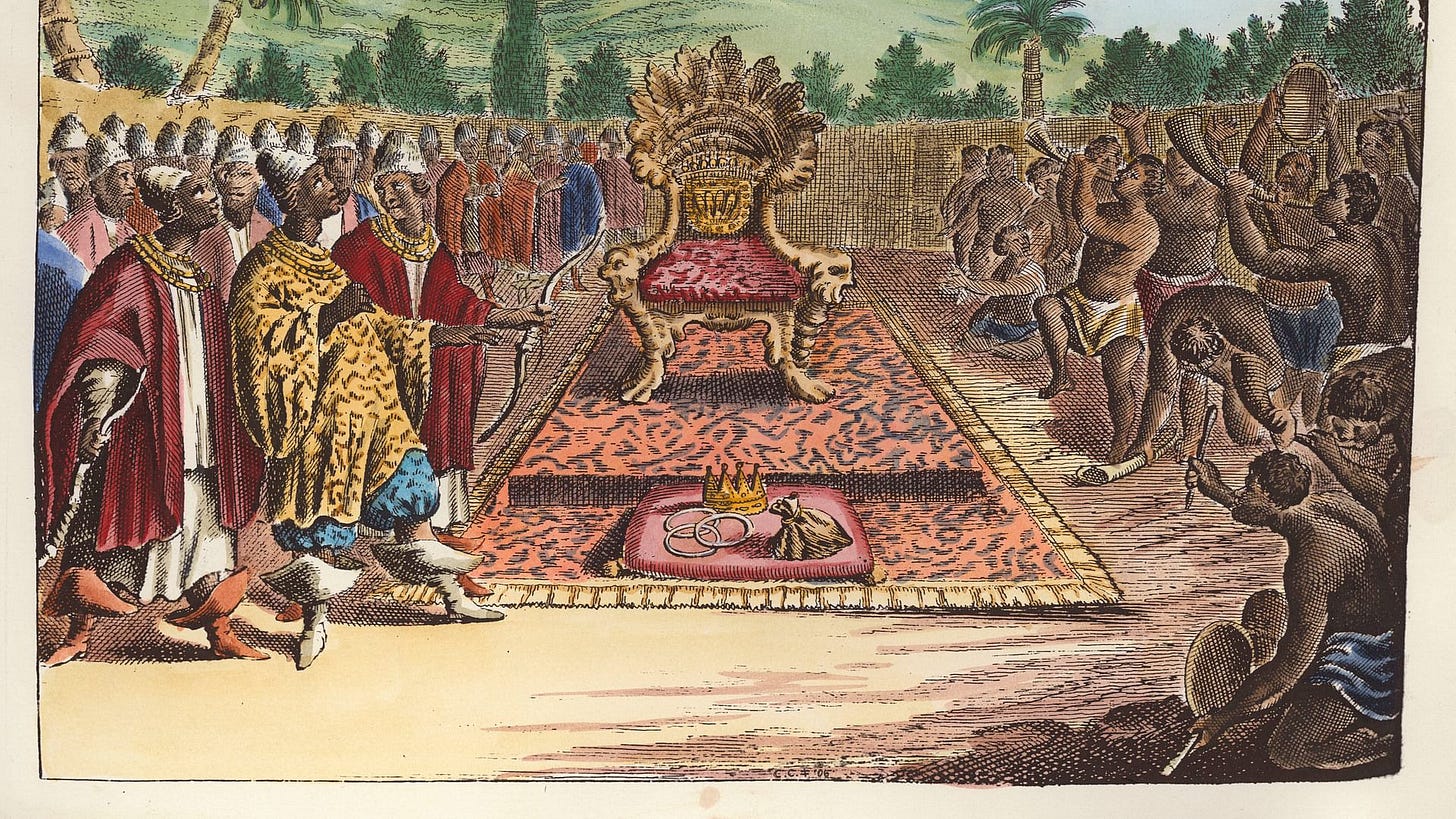

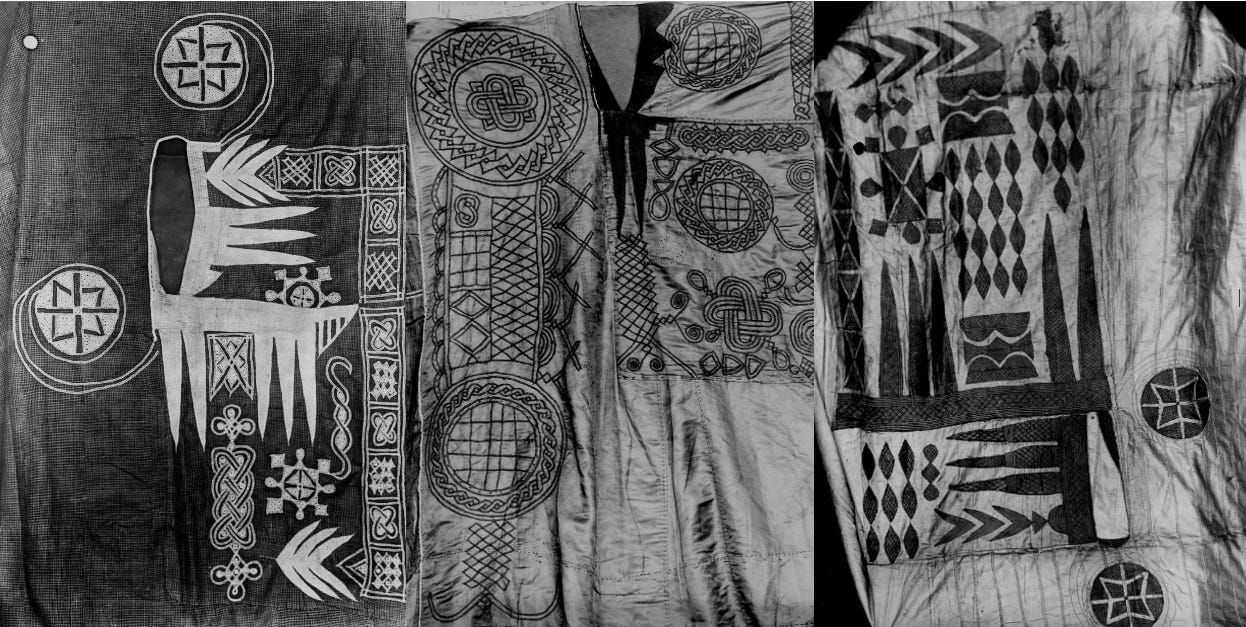

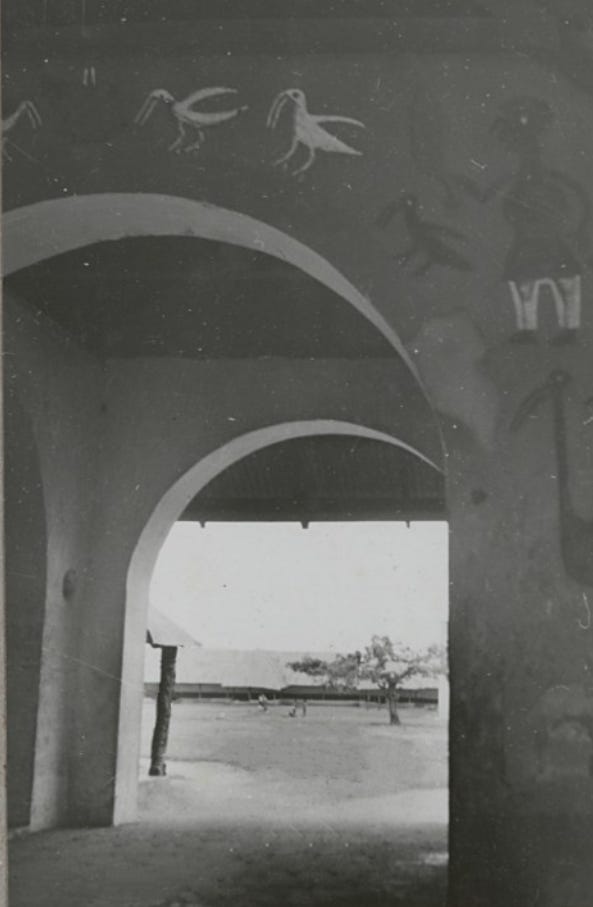

While earlier scholarship emphasized the practical and political motivations behind the rulers’ adoption of Christianity in Kongo, more recent studies have shown that its adoption as a popular religion was shaped by an ideological and iconographic synthesis between the pre-Christian belief systems of Kongo and 16th-century Catholic practices and traditions.

Once established, the Kongolese Church survived through the efforts of its rulers, laypeople, and ordinary subjects, who took the lead in shaping the religion according to their cultural context. According to Cécile Fromont, Kongo’s artwork _**“naturalized Christianity into a local discourse about the nature of the of the supernatural and the cycle of life and death and, in turn, transposed Kongo religious signs into visual expressions of Catholic thought.”**_[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-3-182221546)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!vkzn!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F648a1cfa-8b44-4cf9-81f8-d5ad63439db1_884x578.png)

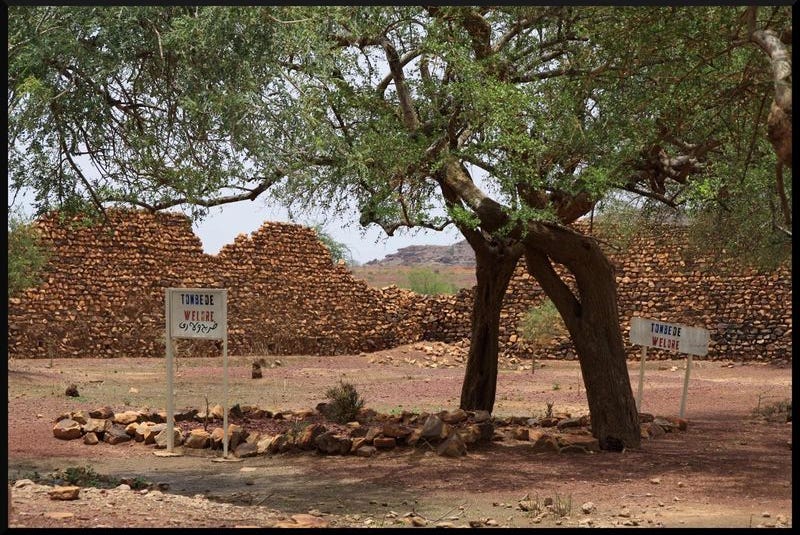

_**Tombs of the Christian kings of Kongo.**_ Mbanza kongo, Angola.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ttnQ!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3913f4e5-aa9d-48eb-8de8-36c39b2140bb_849x621.png)

_**Crucifix.**_ Kongo Kingdom 16th–17th century. Met Museum

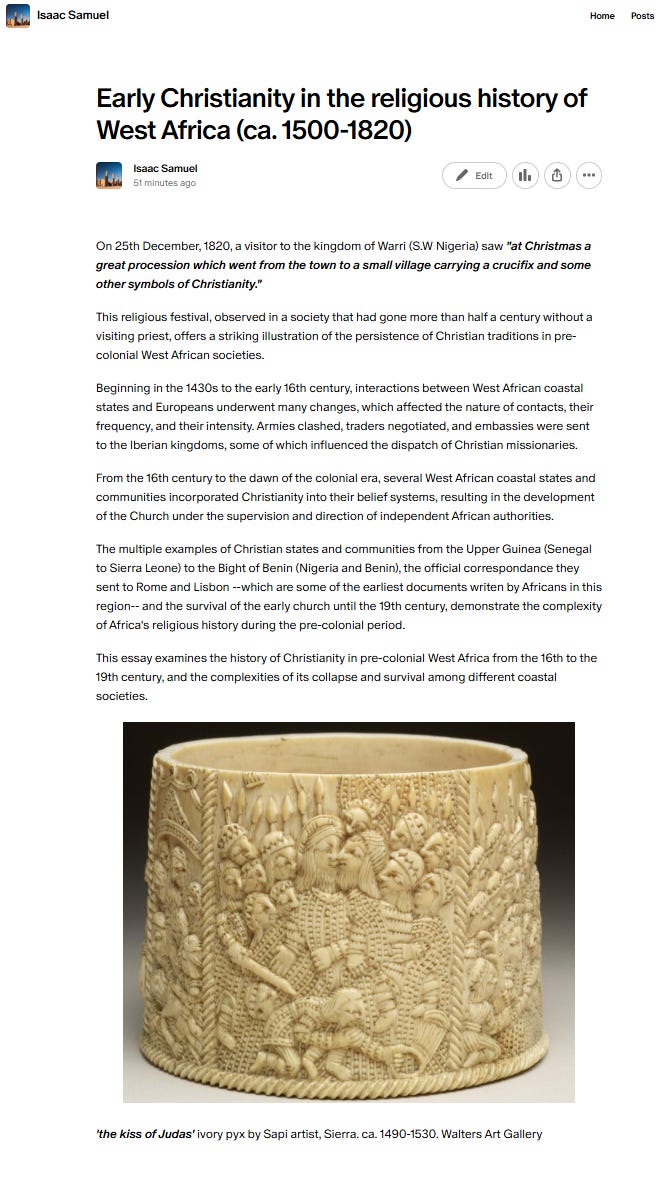

The complexity of the adoption of Christianity in pre-colonial Africa is best illustrated by its early spread among the West African societies of the Upper Guinea (Senegal to Sierra Leone) and the Bight of Benin during the 16th century.

In these regions, local rulers and their subjects actively shaped a distinctly African form of Christianity. While they engaged with visiting priests and sent embassies to the Iberian kingdoms, the church was ultimately established and administered according to indigenous authority, reflecting a deliberate adaptation of Christian practices to local cultural, political, and social contexts.

These West African Christians harmonized existing beliefs and practices common to both West African and Catholic traditions, ensuring that the real institution of the church, both theologically and organizationally, remained under African control.

Once established, internal dynamics unique to each society determined whether the church was abandoned or continued to flourish. In some cases, these Christian polities endured for nearly four centuries after the religion’s initial introduction.

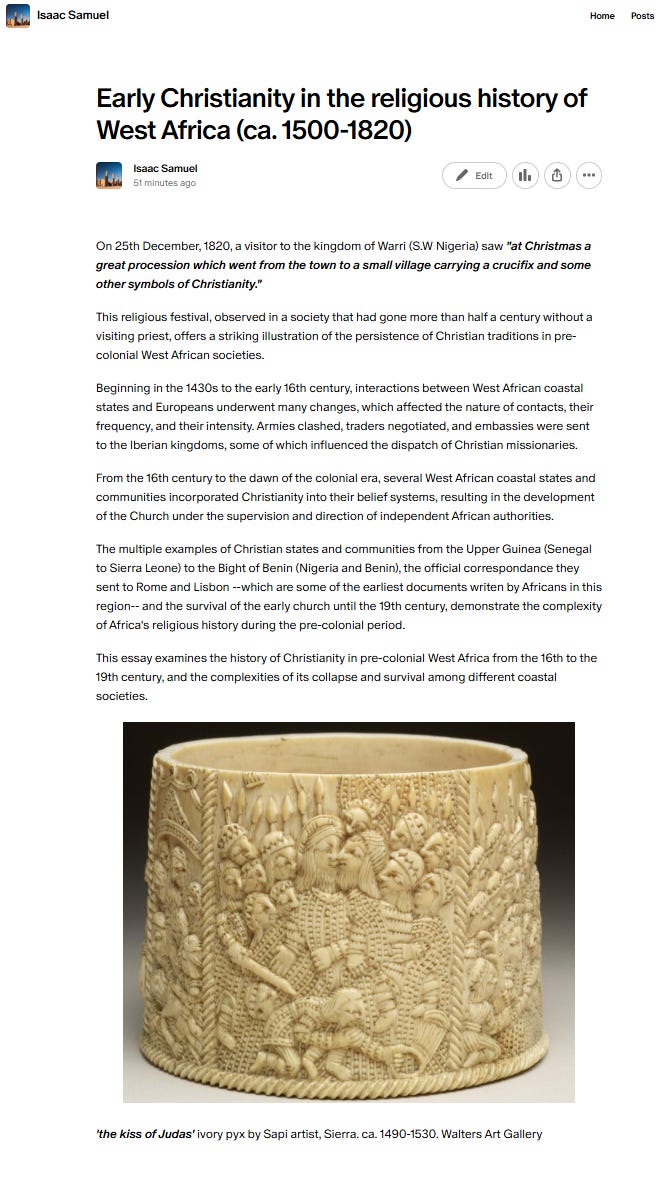

On 25th December, 1820, a visitor to the kingdom of Warri (S.W Nigeria) saw _**“at Christmas a great procession which went from the town to a small village carrying a crucifix and some other symbols of Christianity.”**_

This religious festival, observed in a society that had gone more than half a century without a visiting priest, offers a striking illustration of the persistence of Christian traditions in pre-colonial West African societies.

The history of Christianity in pre-colonial West Africa is the subject of my latest Patreon Article. Please subscribe to read about it here:

[EARLY CHRISTIANITY IN WEST AFRICA](https://www.patreon.com/posts/146362801)

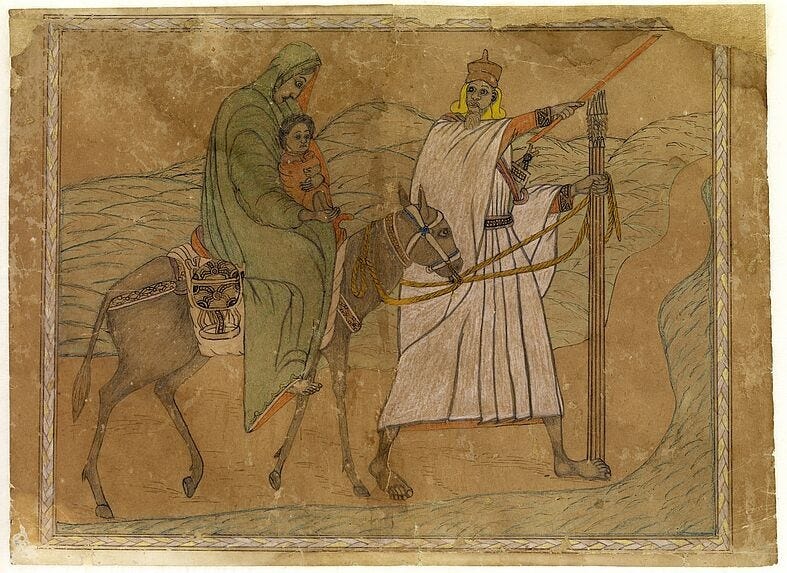

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!HdQJ!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F07ac684e-e46a-4f38-8d6c-5e05760f948d_665x1180.png)

Thanks for reading African History Extra! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-anchor-1-182221546)

Foundations of an African Civilisation: Aksum and the Northern Horn, 1000 BC - AD 1300 By D. W. Phillipson. Church and State in Ethiopa 1270-1527 By Tamrat Tadesse

[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-anchor-2-182221546)

The Roots of Nubian Christianity Uncovered [and] the Triumph of the Last Pharaoh Religious Encounters in Late Antique Africa By Salim Faraji

[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in#footnote-anchor-3-182221546)

The Art of Conversion Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo By Cécile Fromont

[](https://substack.com/profile/134503573-kachi)[](https://substack.com/profile/1133787-patrick-reilly)[](https://substack.com/profile/29353584-samoan62)[](https://substack.com/profile/103915083-dr-d-elisabeth-glassco)[](https://substack.com/profile/379754438-annette)

[62 Likes](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)∙

[9 Restacks](https://substack.com/note/p-182221546/restacks?utm_source=substack&utm_content=facepile-restacks)

62

4

9

Share

#### Discussion about this post

Comments Restacks

[](https://substack.com/profile/312088397-jim-kalbee?utm_source=comment)

[Jim Kalbee](https://substack.com/profile/312088397-jim-kalbee?utm_source=substack-feed-item)

[Dec 21](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in/comment/190312848 "Dec 21, 2025, 7:36 PM")

Liked by isaac Samuel

Isaac Samuel is among the senior faculty at our homeschool. Only 2 students - one is 13, the other almost 80. Lifelong learning in action, pre-colonial West Africa a current multi-year focus. Thank you, Isaac Samuel.

Expand full comment

[Like (3)](javascript:void(0))[Reply](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)

[2 replies by isaac Samuel and others](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in/comment/190312848)

[](https://substack.com/profile/325376762-rekhet-filosofia-africana?utm_source=comment)

[Rekhet | Filosofia Africana](https://substack.com/profile/325376762-rekhet-filosofia-africana?utm_source=substack-feed-item)

[8d](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in/comment/191332394 "Dec 24, 2025, 5:19 PM")

It's interesting to observe that the Christianity in Nubia has flourished by the same political motivation that Mohammed has started a monotheistic religion in Arabic Peninsula and then founded the Islan Religion and, on the other side of Red Sea, Abyssinian Empire has converted to Christianity too: the convention of Roman Empire in Christianity has show that this new spiritual paradigm has arrived and empowered the civilizations. The tragic of all this millennial history is that Ethiopia has became a powerful empire, but Nubians has declined and submitted to a vassall relationship with Meca. The Tragedy of Kongo is just a revival of this assimetric relationship between the colonizer's and the colonizer's cristianities. Thanks for the instigator text

Expand full comment

[Like](javascript:void(0))[Reply](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)[Share](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in)

[2 more comments...](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-christianity-in/comments)

Top Latest Discussions

[Acemoglu in Kongo: a critique of 'Why Nations Fail' and its wilful ignorance of African history.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

[There aren’t many Africans on the list of Nobel laureates, nor does research on African societies show up in the selection committees of Stockholm.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

Nov 3, 2024•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

111

26

26

[The city states of the Yoruba: a history of pre-colonial West African urbanism (1000-1900 CE)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

[At the close of the 19th century, the Yorùbá region of South-west Nigeria was one of the most urbanized places in Africa.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

Sep 7, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

59

6

8

[Africans in the Indian Ocean world and the autobiography of a Somali Globetrotter.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

[In 1944, a soldier on Australia’s most remote northern coastline discovered a handful of copper coins that were originally minted in the medieval…](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

Aug 17, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

66

4

11

See all

### Ready for more?

Subscribe

© 2026 isaac Samuel · [Privacy](https://substack.com/privacy) ∙ [Terms](https://substack.com/tos) ∙ [Collection notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected)

[Start your Substack](https://substack.com/signup?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=web&utm_content=footer)[Get the app](https://substack.com/app/app-store-redirect?utm_campaign=app-marketing&utm_content=web-footer-button)

[Substack](https://substack.com/) is the home for great culture

|

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa

|

Published Time: 2024-09-01T16:25:54+00:00

A brief history of Gold in Africa and the emporium of Sofala.

===============

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

[African History Extra](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

=============================================================

Subscribe Sign in

Discover more from African History Extra

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Over 15,000 subscribers

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

Already have an account? [Sign in](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa)

A brief history of Gold in Africa and the emporium of Sofala.

=============================================================

[](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

Sep 01, 2024

33

1

3

Share

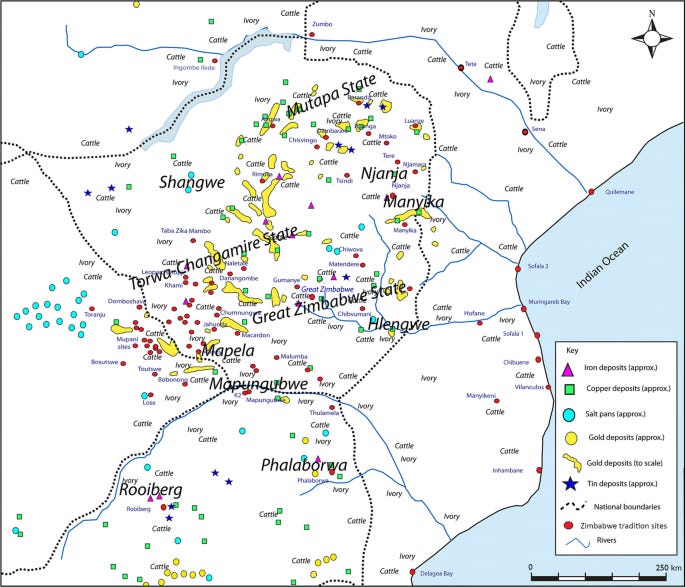

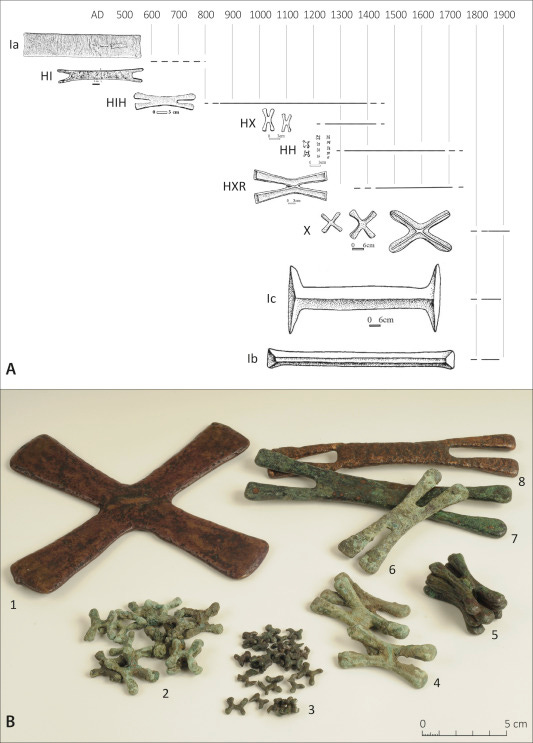

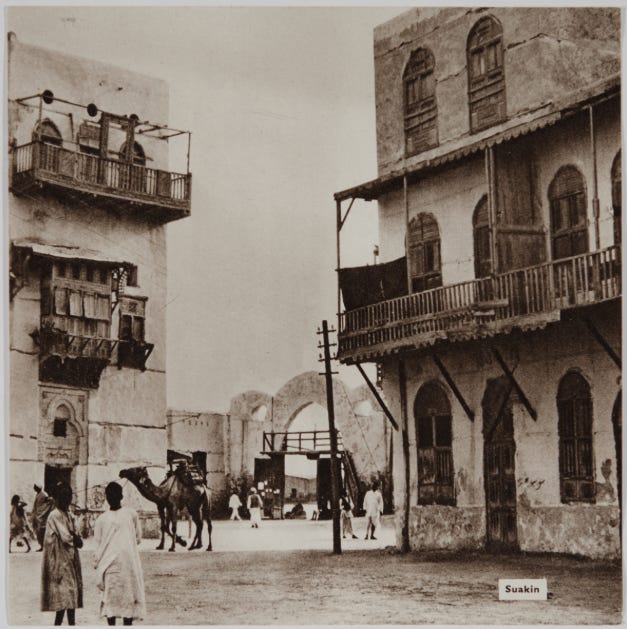

It was copper, not Gold, that was considered the most important metal in most African societies, according to an authoritative study by Eugenia Herbert. Employing archaeological evidence as well as historical documentation, Herbert concluded that copper had more intrinsic value than Gold and that the few exceptions reflected a borrowed system of values from the Muslim or Christian worlds.[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-1-148365888)

However, more recent historical investigations into the relative values of Gold and Copper across different African societies undermine this broad generalization. While there's plenty of evidence that Copper and its alloys were indeed the most valued metal in many African societies, there has also been increasing evidence for the importance of Gold in several societies across the continent that cannot solely be attributed to external influence.

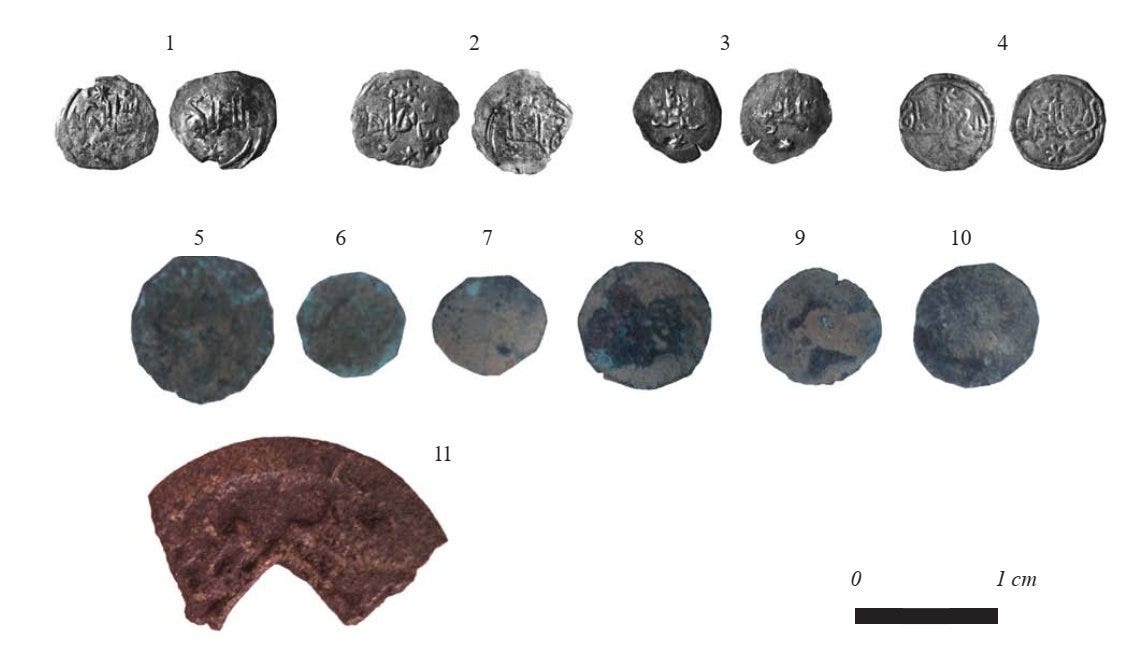

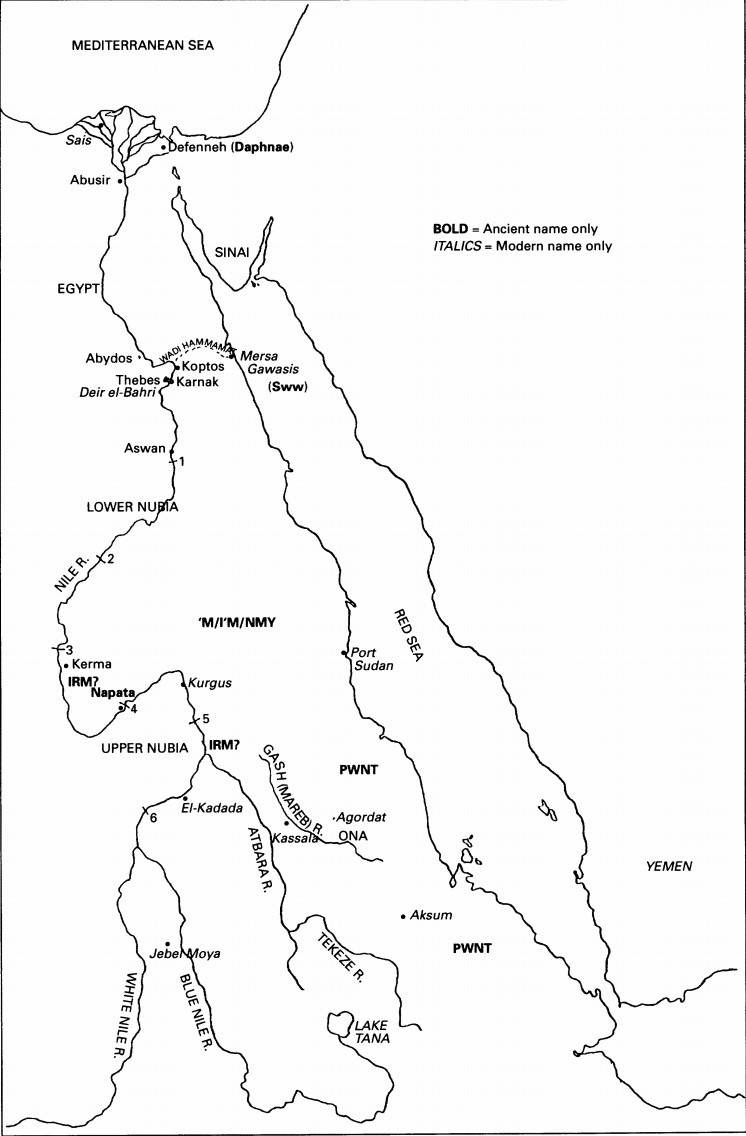

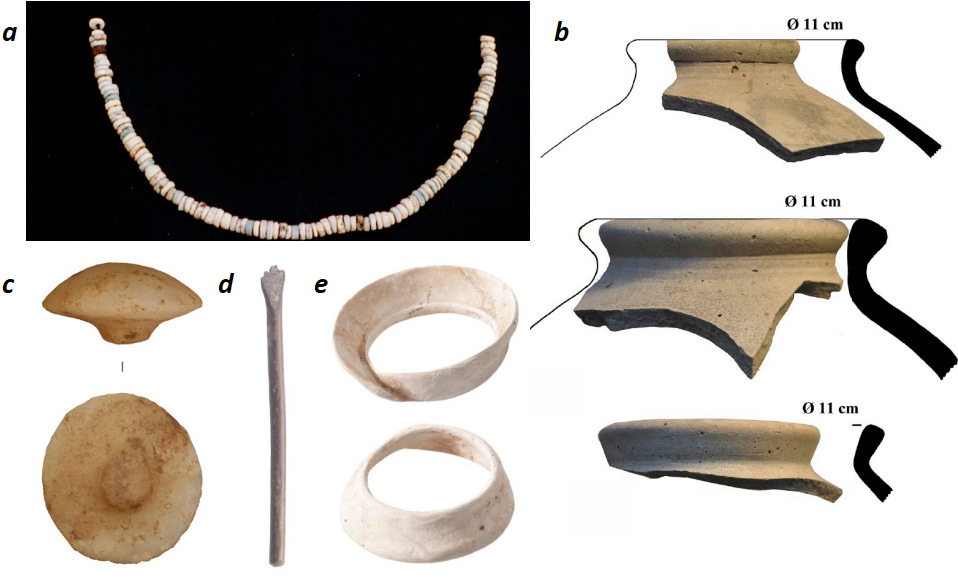

In ancient Nubia where some of the continent's oldest gold mines are found, Gold objects appear extensively in the archaeological record of the kingdoms of Kerma and Kush. Remains of workshops of goldsmiths at the capital of classic Kerma and Meroe, ruins of architectural features and statues covered in gold leaf, inscriptions about social ceremonies involving the use of gold dust and objects, as well as finds of gold jewelry across multiple sites along the Middle Nile, provide evidence that ancient Nubia wasn't just an exporter of Gold, but also a major consumer of the precious metal.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-2-148365888)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ond8!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5a98e751-c4a5-4204-8607-6b3c006c0258_1182x578.png)

_**Gold objects from ancient Nubia at the Boston Museum**_; Bronze dagger from Kerma with gilded hilt, 18th century. BC, Isis gold pectoral from Napata, 6th century BC, earrings and ear studs from Meroe, 1st century BC-3rd century CE.

In the Senegambia region of west Africa, where societies of [mobile herders constructed megaliths and tumuli graves dating back to the 2nd millennium BC](https://www.patreon.com/posts/unlocking-of-of-68055326), a trove of gold objects was included in the array of finery deposited to accompany their owners into the afterlife. The resplendent gold pectoral of Rao, dated to the 8th century CE is only the best known among the collection of gold objects from the Senegambia region that include gold chains and gold beads from the Wanar and Kael Tumulus, dated to the 6th century CE, which predate the Islamic period.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-3-148365888)

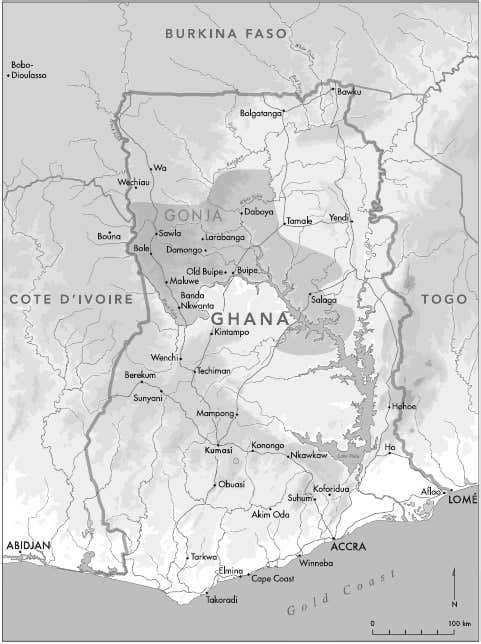

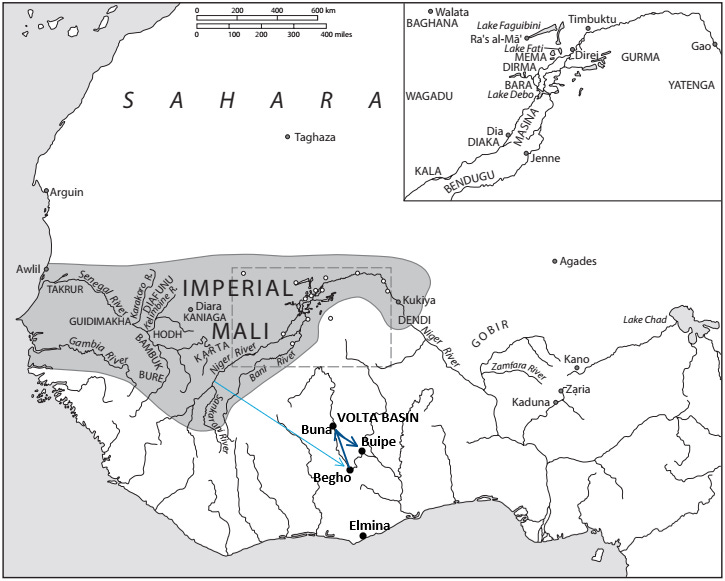

Equally significant is the better-known region of the Gold Coast in modern Ghana, where many societies, especially among the Akan-speaking groups, were renowned for gold mining and smithing. The rulers of the earliest states which emerged around the 13th century at Bono-Manso and later at Denkyira and Asante in the 17th and 18th centuries, placed significant value on gold, which was extracted from deep ancient mines, worked into their royal regalia, stored in the form of gold dust, and sold to the [Wangara merchants from Mali](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/foundations-of-trade-and-education).[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-4-148365888)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fFE_!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5c426345-3ade-4bdc-a402-e497062dd9f4_1100x536.png)

_**Rao pectoral**_, 8th century CE, Senegal, Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop._**Pendant dish, Asante kingdom**_, 19th century, Ghana, British Museum.

While Africa's gold exports increased during the Islamic era and the early modern period, the significance of these external contacts to Africa's internal demand for gold was limited to regions where there was pre-existing local demand.

For example, despite the numerous accounts of the golden caravans from Medieval Mali such as the over 12 tonnes of gold carried by Mansa Musa in 1324, no significant collection of gold objects has been recovered from the region (compared to the many bronze objects found across Mali’s old cities and towns). A rare exception is the 19th-century treasure of Umar Tal that was **stolen**by the French from Segou, which included 75kg of gold and over 160 tons of silver.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-5-148365888)

Compare this to the Gold Coast which exported about 1 tonne of gold annually[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-6-148365888), and where hundreds of gold objects were **stolen** by the British from the Asante capital Kumasi, during the campaigns of 1826, 1874, and 1896[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-7-148365888), with at least 239 items housed at the British Museum, not counting the dozens of other institutions and the rest of the objects which were either melted or surrendered as part of the indemnity worth 1.4 tonnes of gold. Just one of these objects, eg the gold head at London’s Wallace collection, weighs 1.36 kg.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KcQg!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2eb84e45-9e72-4155-a275-98c36c025768_964x411.png)

_**‘Trophy head’ from Asante, Ghana. 18th-19th century**_, Wallace Collection.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Op0q!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe4350574-daa6-4d74-bf64-f017bf0b5a66_1234x539.png)

_**Gold jewelry, Wolof artist, late 19th-early 20th century**_, Senegal & Mauritania. Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Museum.

Domestic demand for gold in Africa was thus largely influenced by local value systems, with external trade being grafted onto older networks and patterns of exchange. Examples of these patterns of internal gold trade and consumption abound from Medieval Nubia to the Fulbe and Wolof kingdoms of the Senegambia, to the northern Horn of Africa.

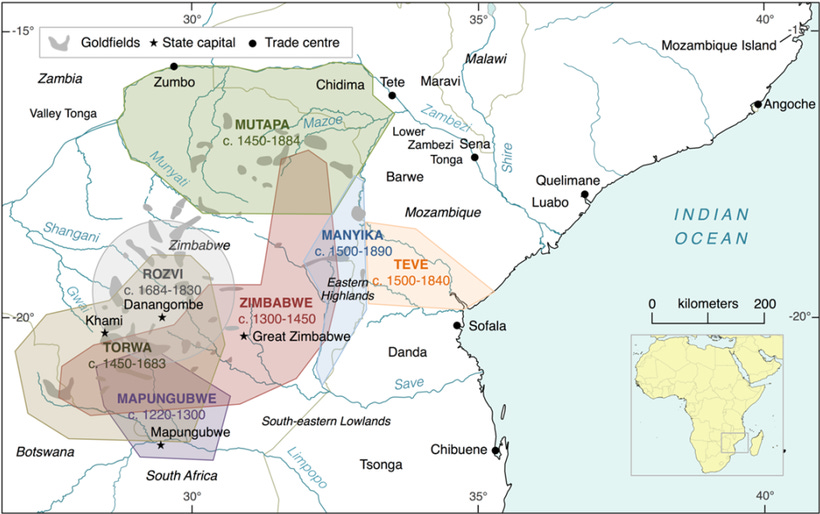

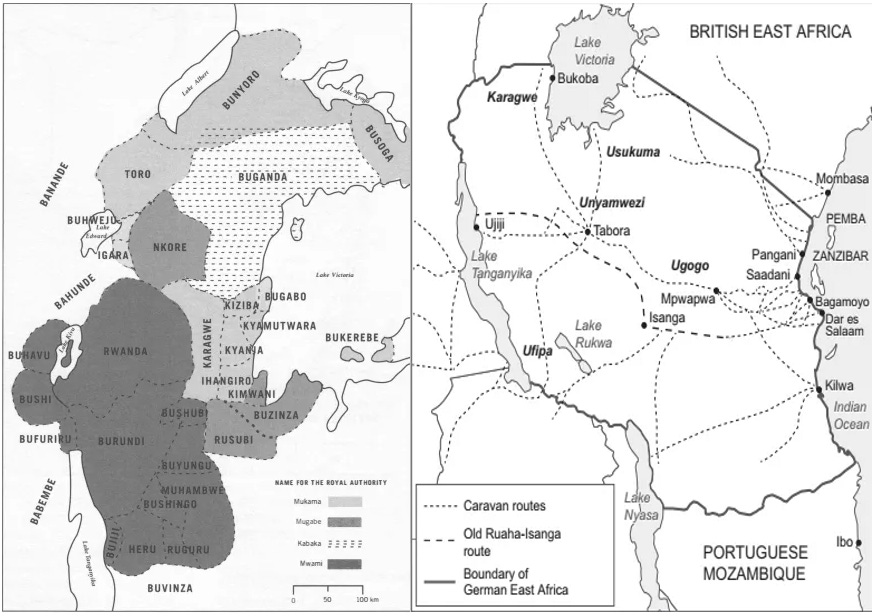

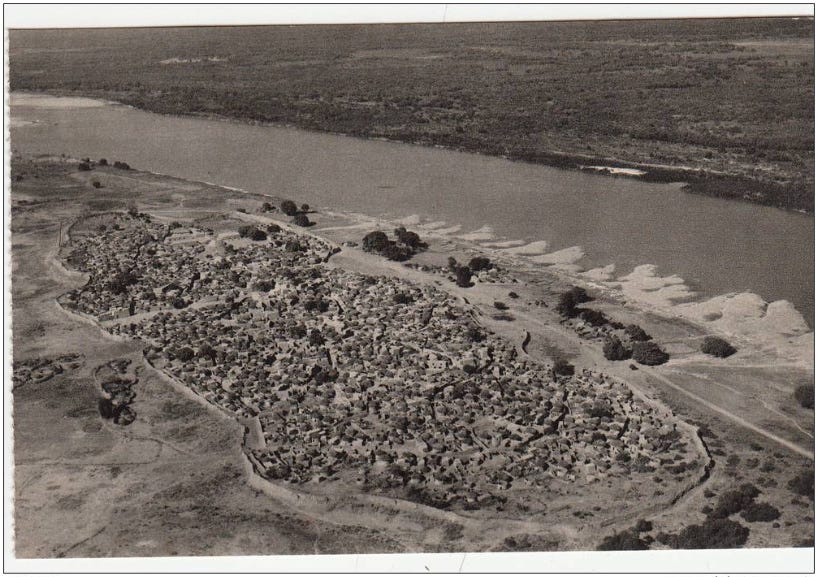

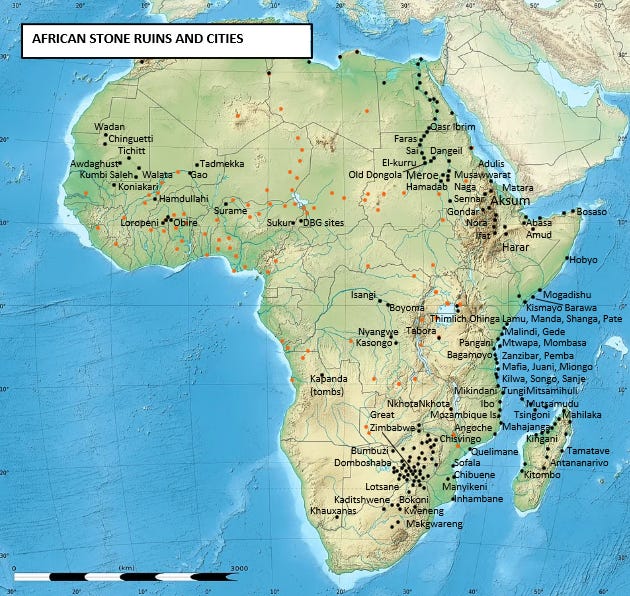

This interplay between internal and external demand for gold is well attested in the region of south-east Africa where pre-existing demand for gold —evidenced by the various collections of gold objects from the many stone ruins scattered across the region— received further impetus from the Swahili city-states of the East African coast through the port town of Sofala in modern Mozambique.

At its height in the 15th century, an estimated 8.5 tonnes of gold went through Sofala each year, making it one of the world's biggest gold exporters of the precious metal.

**The history of the Gold trade of Sofala and the internal dynamics of gold demand within Southeast Africa and the Swahili coast is the subject of my latest Patreon article,**

**Please subscribe to read about it here:**

[THE GOLD TRADE OF SOFALA](https://www.patreon.com/posts/dynamics-of-gold-111163742?utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=postshare_creator&utm_content=join_link)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!SaNC!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff6a52d61-fe50-4be0-a461-be4f733af8ce_675x1090.png)

* * *

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qqKZ!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F32dfd7c9-0de4-40ea-9db2-bb4f88b1698f_811x583.png)

_**Pair of wooden sandals, covered with an ornamented silver sheet with borders made of attached silver drops, and a golden knob for support**_. Swahili artist, 19th century, Tanzania. SMB museum.

Thanks for reading African History Extra! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-1-148365888)

Red Gold of Africa: Copper in Precolonial History and Culture by Eugenia W. Herbert

[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-2-148365888)

Black Kingdom of the Nile by Charles Bonnet pg 29, 49, 62, 65, 169-173, The Image of the Ordered World in Ancient Nubian Art By László Török pg 82,85, 315, 472-473, The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization By László Török pg 112-121, 457, 460, 528)

[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-3-148365888)

Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara By Alisa LaGamma pg 51-54, Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa by Kathleen Bickford Berzock pg 181.

[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-4-148365888)

The State of the Akan and the Akan States by I. Wilks pg 240-246, The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa By Timothy Insoll pg 340-342,

[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-5-148365888)

_**emphasis on ‘stolen’ here is to highlight how colonial warfare and looting may be responsible for the lack of significant archeological finds of gold objects from this region, considering how the majority of gold would have been kept in treasuries rather than buried. Excavations in Ghana for example have yet to recover any significant gold objects, despite the well-known collections of such objects in many Western institutions.**_ Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange Across Medieval Saharan Africa by Kathleen Bickford Berzock pg 179-180.

[6](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-6-148365888)

From Slave Trade to 'Legitimate' Commerce: The Commercial Transition in Nineteenth-Century West Africa by Robin Law pg 97

[7](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa#footnote-anchor-7-148365888)

_the 1826 loot included £2m worth of gold and a nugget weighing 20,000 ounces, the 1874 loot included dozens of gold objects including several masks, with one weighing 41 ounces, part of the 1874 indemnity of 50,000 ounces was paid in gold objects shortly after, and again in 1896._ see; The Fall of the Asante Empire by Robert B. Edgerton, Asante in the Nineteenth Century By Ivor Wilks

* * *

#### Subscribe to African History Extra

By isaac Samuel · Launched 4 years ago

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

[](https://substack.com/profile/255628153-the-africa-review)[](https://substack.com/profile/110412978-aj)[](https://substack.com/profile/98635331-alton-mark-allen)[](https://substack.com/profile/29353584-samoan62)[](https://substack.com/profile/10684878-david-perlmutter)

[33 Likes](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa)∙

[3 Restacks](https://substack.com/note/p-148365888/restacks?utm_source=substack&utm_content=facepile-restacks)

33

1

3

Share

#### Discussion about this post

Comments Restacks

[1 more comment...](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-history-of-gold-in-africa/comments)

Top Latest Discussions

[Acemoglu in Kongo: a critique of 'Why Nations Fail' and its wilful ignorance of African history.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

[There aren’t many Africans on the list of Nobel laureates, nor does research on African societies show up in the selection committees of Stockholm.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/acemoglu-in-kongo-a-critique-of-why)

Nov 3, 2024•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

111

26

26

[The city states of the Yoruba: a history of pre-colonial West African urbanism (1000-1900 CE)](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

[At the close of the 19th century, the Yorùbá region of South-west Nigeria was one of the most urbanized places in Africa.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-city-states-of-the-yoruba-a-history)

Sep 7, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

59

6

8

[Africans in the Indian Ocean world and the autobiography of a Somali Globetrotter.](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

[In 1944, a soldier on Australia’s most remote northern coastline discovered a handful of copper coins that were originally minted in the medieval…](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/africans-in-the-indian-ocean-world)

Aug 17, 2025•[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

66

4

11

See all

### Ready for more?

Subscribe

© 2026 isaac Samuel · [Privacy](https://substack.com/privacy) ∙ [Terms](https://substack.com/tos) ∙ [Collection notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected)

[Start your Substack](https://substack.com/signup?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=web&utm_content=footer)[Get the app](https://substack.com/app/app-store-redirect?utm_campaign=app-marketing&utm_content=web-footer-button)

[Substack](https://substack.com/) is the home for great culture

|

https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century

|

Published Time: 2024-03-03T16:30:13+00:00

a brief note on Africa in 16th century global history.

===============

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

[African History Extra](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/)

=============================================================

Subscribe Sign in

Discover more from African History Extra

All about African history; narrating the continent's neglected past

Over 15,000 subscribers

Subscribe

By subscribing, I agree to Substack's [Terms of Use](https://substack.com/tos), and acknowledge its [Information Collection Notice](https://substack.com/ccpa#personal-data-collected) and [Privacy Policy](https://substack.com/privacy).

Already have an account? [Sign in](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century)

a brief note on Africa in 16th century global history.

======================================================

### the international relations and manuscripts of Kongo

[](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/@isaacsamuel)

Mar 03, 2024

23

2

3

Share

The 16th century was one the most profound periods of change in Africa's international relations.

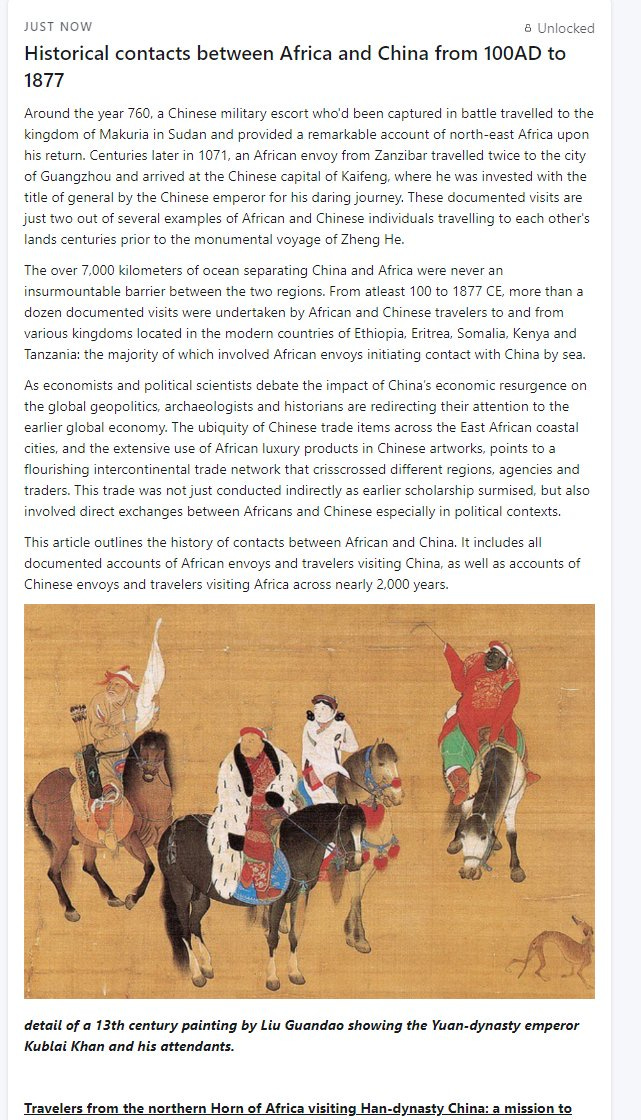

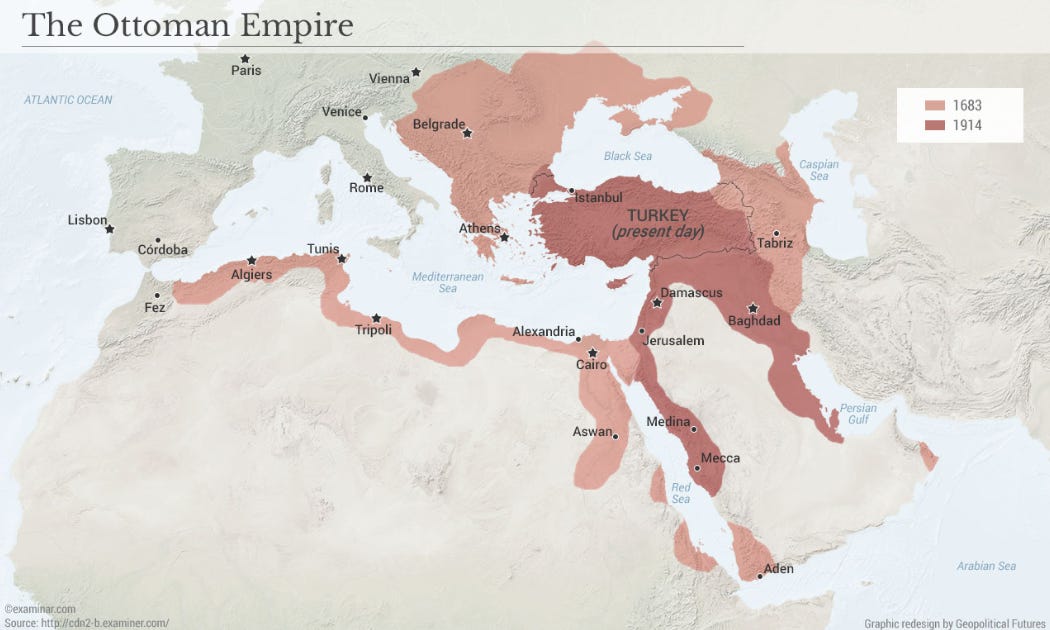

Africans had led the initiative in establishing international contact across Eurasia[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-1-142265250), and the expansion of the Ottoman and Portuguese empires in the 16th century further accelerated Africa's engagement with the rest of the world, reshaping pre-existing patterns of regional alliances and rivalries.

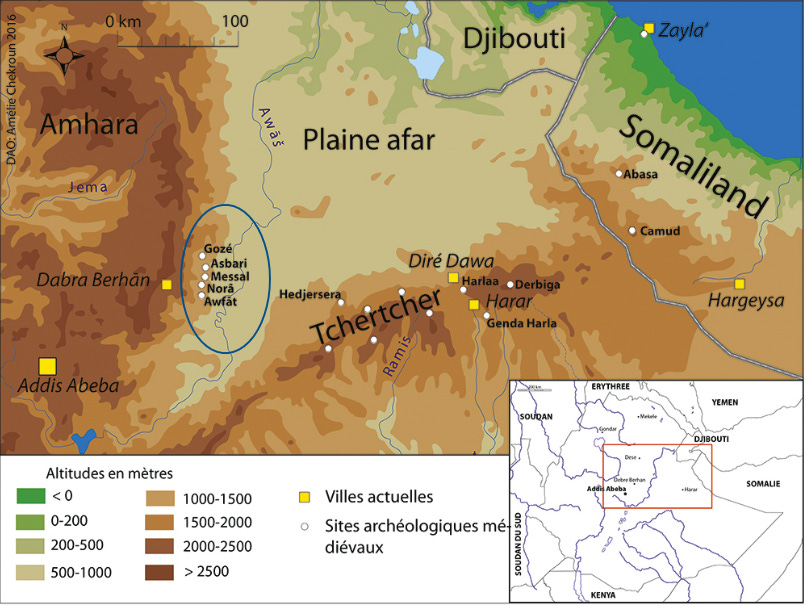

In the northern Horn of Africa, the armies of the Adal sultanate defeated the Ethiopian forces in 1529 as their leader, Imam Ahmad al-Ghazi, launched a series of successful campaigns that briefly subsumed most of Ethiopia. Al-Ghazi's campaigns eventually acquired an international dimension and became increasingly enmeshed in the global conflict between the Portuguese and the Ottomans. The Turks supplied al-Ghazi with firearms and soldiers, while the Portuguese provided the same to the Ethiopian ruler Gelawdewos, who eventually won the war in 1543.

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9_IF!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcf939165-cea3-488a-adb1-0d27b64ed7ae_820x599.png)

**‘Futuh al-Habasa’** (_Conquest of Abyssinia_) written by Sihab ad-Din Ahmad bin Abd al-Qader in 1559, copy at the King Saud University.[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-2-142265250)

Around the same time, the rulers of the Swahili city-states along the East African coast who were opposed to the Portuguese presence sent envoys to the Ottoman provinces in Arabia beginning in 1542, looking for allies to aid them in expelling the Portuguese. After several more embassies in the 1550s and 60s, Ottoman corsair Ali Beg brought his forces to the East African coast in 1585 and 1589, but was eventually forced to withdraw after an army from the mainland drove his forces from the coast.[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-3-142265250)

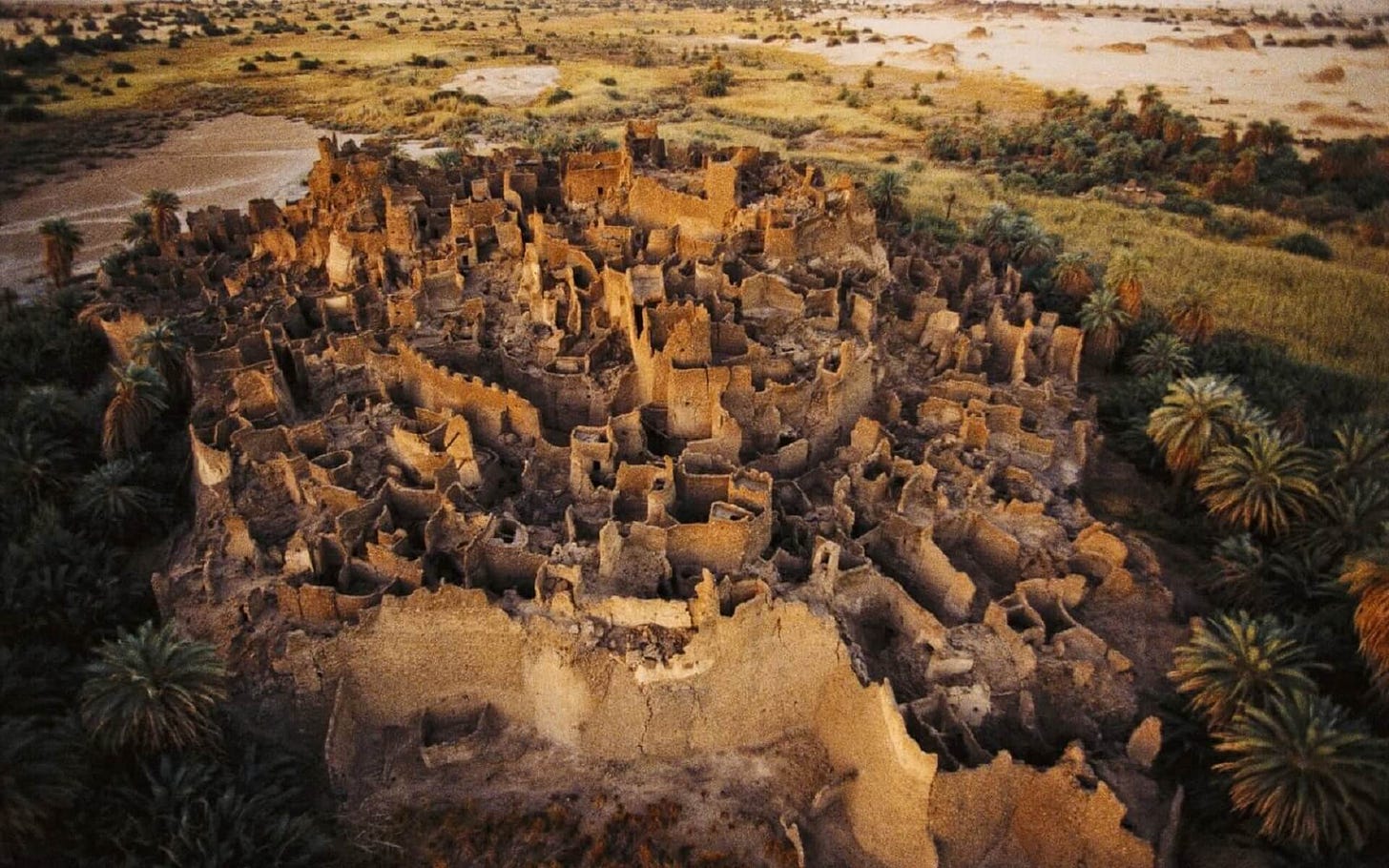

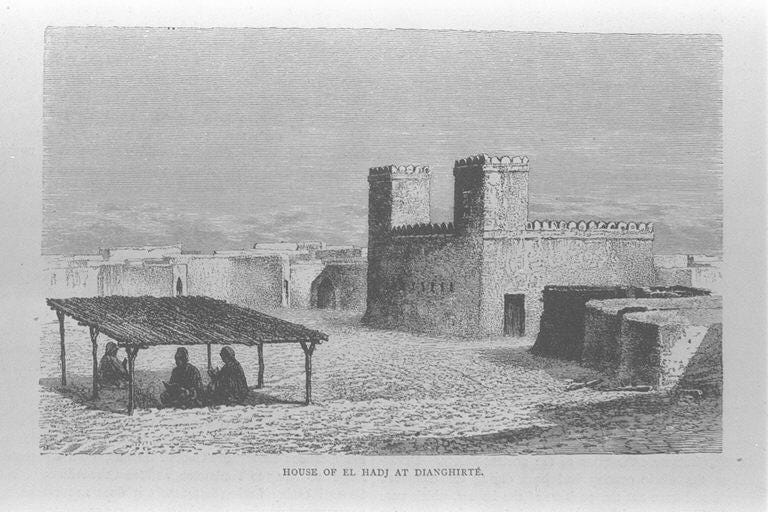

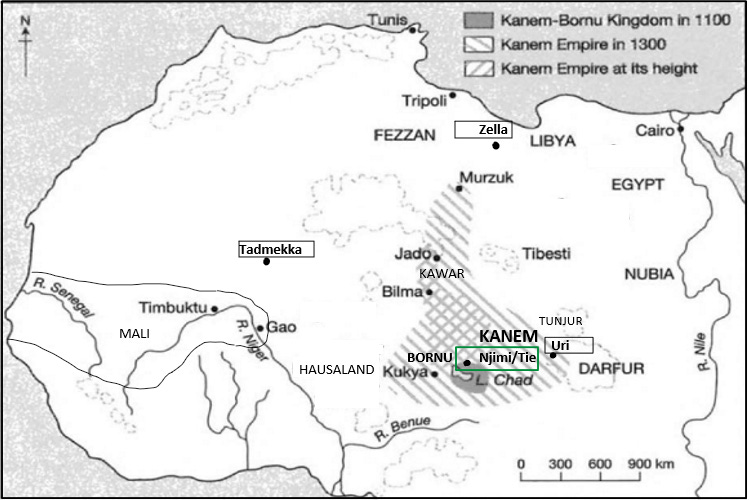

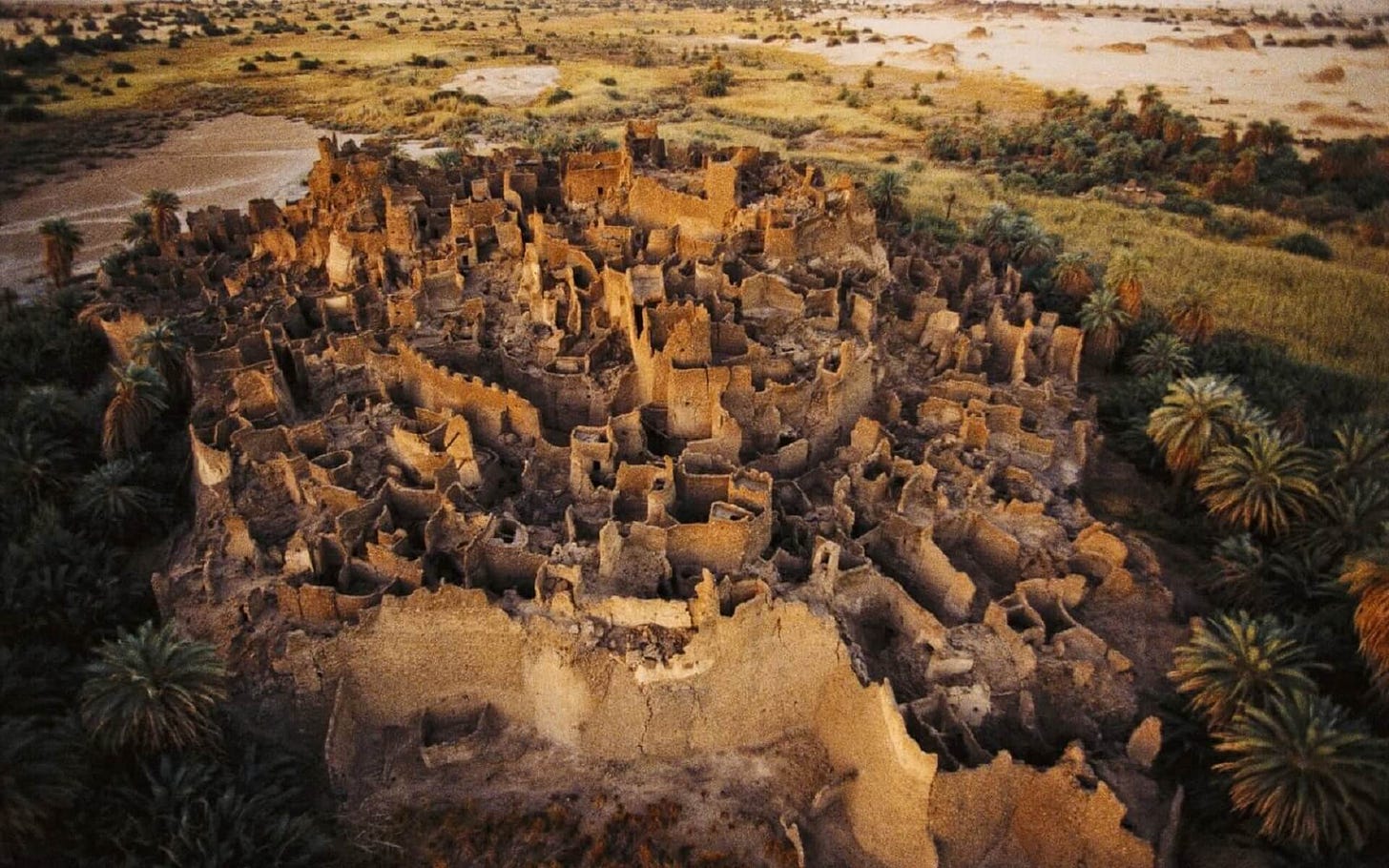

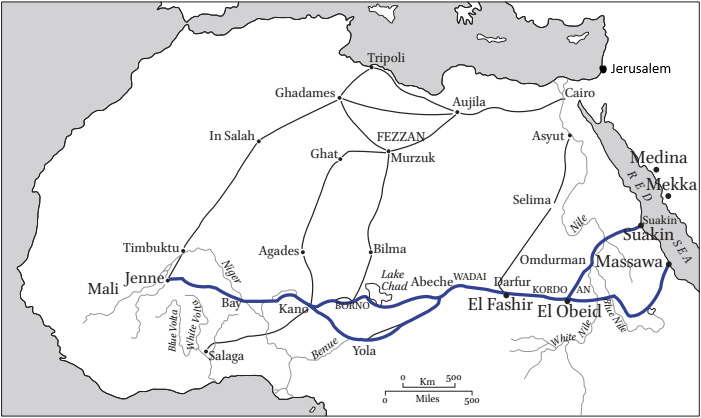

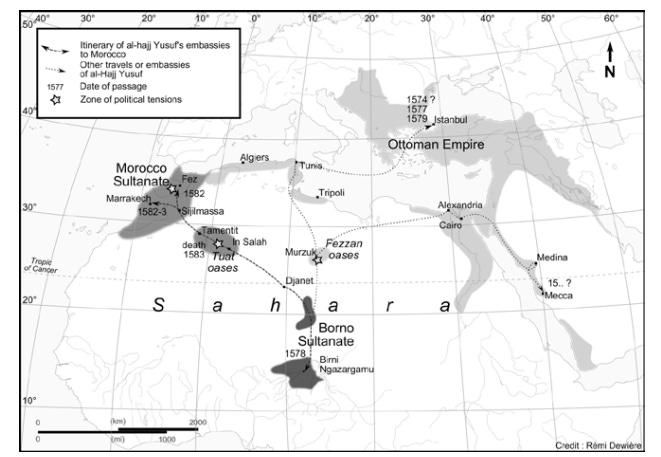

On the other side of the continent the simultaneous expansion of the Portuguese and Ottomans into north-western Africa threatened the regional balance of power between the empires of Morocco and Bornu. After a series of diplomatic initiatives by Bornu’s envoys to Marrakech and Istanbul, the Moroccans defeated the Portuguese in 1578, just as Bornu's ruler Mai Idris Alooma was halting the Ottoman advance into Bornu’s dependancies in southern Libya.[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-4-142265250)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!nsuc!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe40c72d1-dcff-44cf-a7ef-eee34186e979_820x615.jpeg)

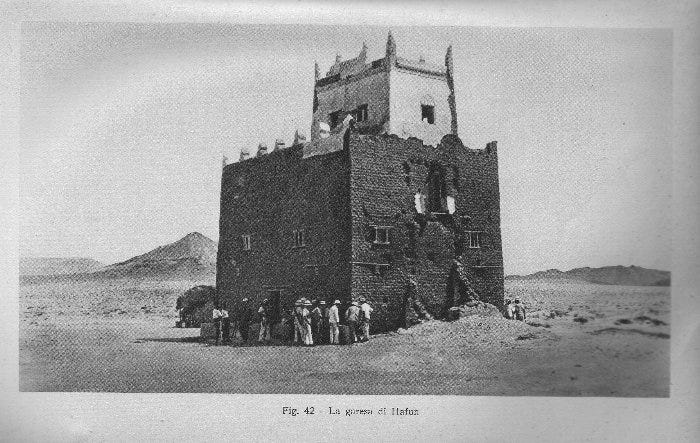

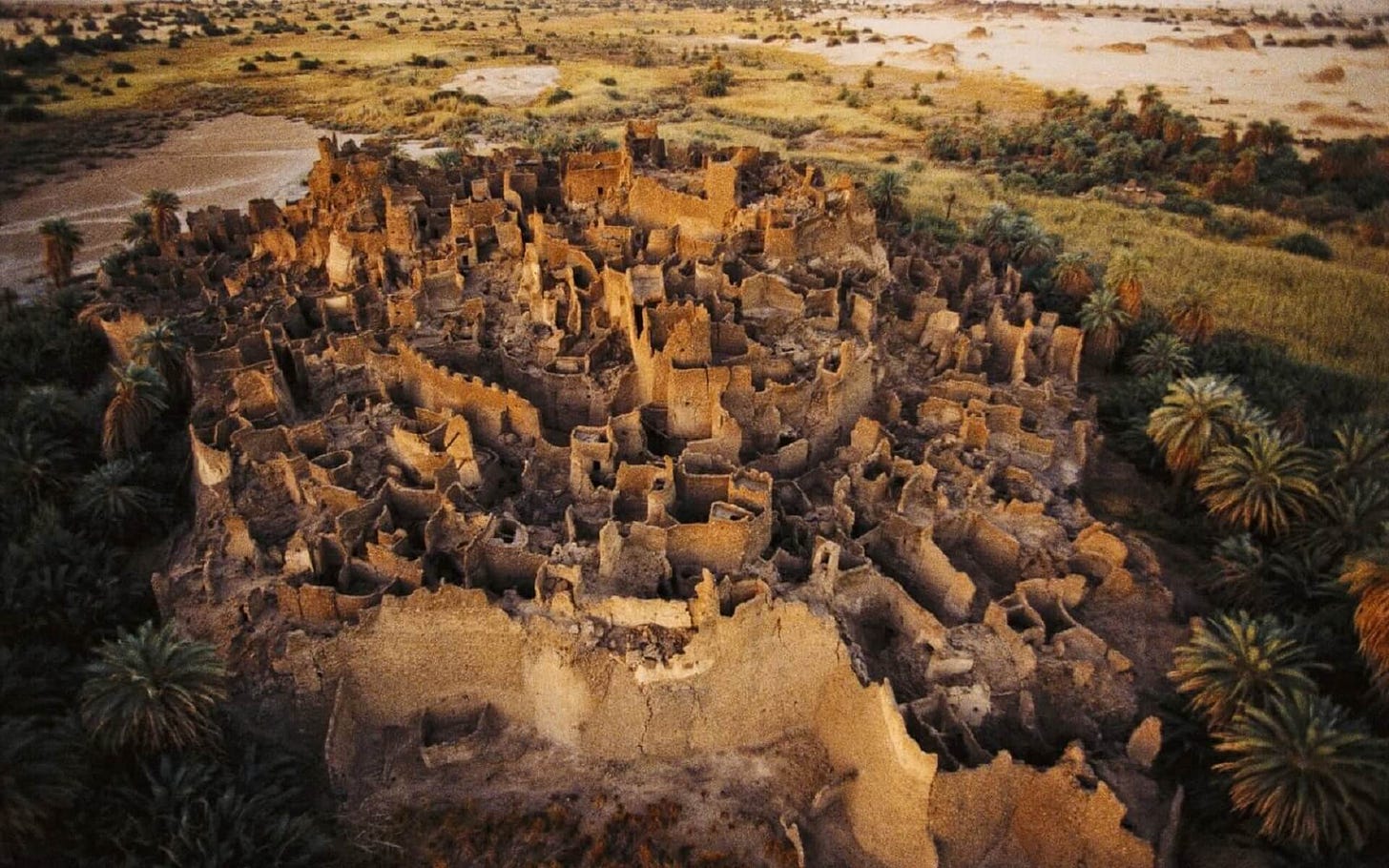

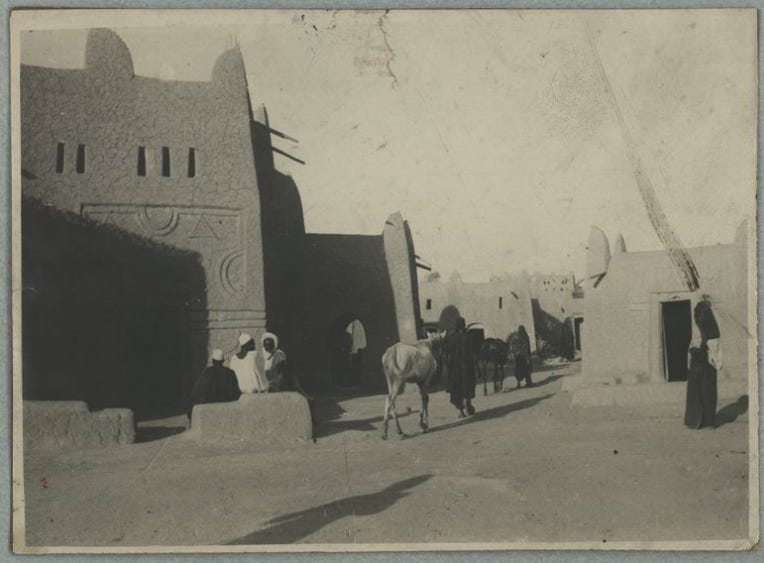

_**the 16th century fortress of Murzuq in southern Libya’s Fezzan region, associated with the Awlad dynasty, a client state of Bornu**_. The fezzan remained the border between Bornu and the Ottomans and it was from this region that **[Bornu acquired european slave soldiers and firearms from the Ottomans](https://www.patreon.com/posts/first-guns-and-84319870)**.

In all three regions, the globalized rivalries between the regional powers are mentioned in some of Africa's best known works of historical literature. The chronicle on Adal’s ‘_Conquest of Abyssinia’_ was completed in 1559, in the same decade that the chronicle of the Swahili city of Kilwa was written, and not long before the Bornu scholar Aḥmad Furṭū would complete the first chronicle of Mai Idris' reign in 1576. While all three chronicles are primarily concerned with domestic politics, they also include an international dimension regarding the diplomatic activities of their kingdoms.[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-5-142265250)

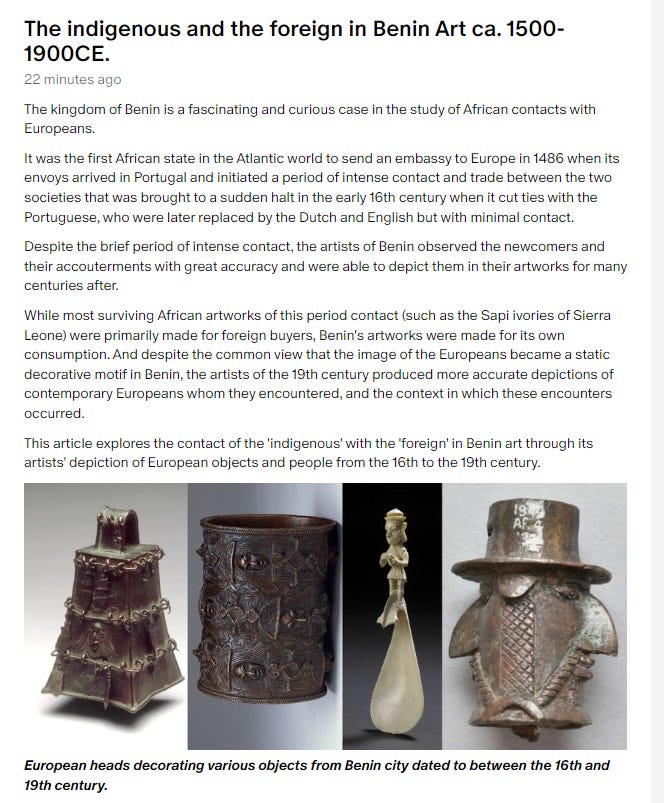

Much further south in the region of west-central Africa, another African society entered the international arena, without engaging in the global rivaries of the period. The sudden entry of the kingdom of Kongo into global politics and the emergence of its intellectual tradition was one of the most significant yet often misunderstood developments in 16th-century Africa.

**The international activities of the kingdom of Kongo and its intellectual traditions are the subject of my latest Patreon article.**

**please subscribe to read about it here:**

[KONGO'S FOREIGN RELATIONS & MANUSCRIPTS](https://www.patreon.com/posts/99646036)

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ri8t!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7935d194-6756-43b8-8e1e-532551f30444_648x1186.png)

* * *

[](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!JG-n!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F437706fb-81d4-4c72-bfd6-bae06e7bbcf8_688x604.png)

_**The ambassador Antonio Emanuele Ne Vunda of the Kingdom of Kongo and the embassy of Hasekura Tsunenaga of Japan**_. Painting by Agostino Taschi. ca. 1616 in the Sala dei Corazzieri, Palazzo del Quirinale., Rome

* * *

Thanks for reading African History Extra! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribe

[1](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-anchor-1-142265250)

**[Did Europeans Discover Africa? Or Was It the Other Way Around?](https://newlinesmag.com/essays/did-europeans-discover-africa-or-the-other-way-around/)**

[2](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-anchor-2-142265250)

[Link](https://makhtota.ksu.edu.sa/makhtota/2400/56)

[3](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-anchor-3-142265250)

[The Portuguese and the Swahili, from foes to unlikely partners: Afro-European interface in the early modern era ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-portuguese-and-the-swahili-from)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/profile/44604452-isaac-samuel)

·

March 13, 2022

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-portuguese-and-the-swahili-from)

Studies of early Afro-European history are at times plagued by anachronistic theories used by some scholars, who begin their understanding of the era from the perspective of colonial Africa and project it backwards to the 16th and 17th centuries when first contacts were made; such as those between the Swahili and the Portuguese. They construct an image …

[Read full story](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/the-portuguese-and-the-swahili-from)

[4](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-anchor-4-142265250)

[Morocco, Songhai, Bornu and the quest to create an African empire to rival the Ottomans. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/morocco-songhai-bornu-and-the-quest)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/profile/44604452-isaac-samuel)

·

January 30, 2022

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/morocco-songhai-bornu-and-the-quest)

The Sahara has for long been perceived as an impenetrable barrier separating “north africa” from “sub-saharan Africa”. The barren shifting sands of the 1,000-mile desert were thought to have constrained commerce between the two regions and restrained any political ambitions of states on either side to interact. This “desert barrier” theory was populariz…

[Read full story](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/morocco-songhai-bornu-and-the-quest)

[5](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/a-brief-note-on-africa-in-16th-century#footnote-anchor-5-142265250)

[An African-centered intellectual world; the scholarly traditions and literary production of the Bornu empire (11th-19th century) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/an-african-centered-intellectual)

[isaac Samuel](https://substack.com/profile/44604452-isaac-samuel)

·

September 11, 2022

[](https://www.africanhistoryextra.com/p/an-african-centered-intellectual)

Studies of African scholarship in general, and west African scholarship in particular, are often framed within diffusionist discourses, in which African intellectual traditions are "received” from outside and are positioned on the periphery of a greater system beyond the continent